Disk disease: It's not just for dogs

Follow Pollux's tale, and discover more about disk disease in cats.

We all want to do what's best for our pets. As technicians, we hold ourselves to a higher standard because of our additional training and education, but even we can still fall into typical assumptions. This article is about my cat's experience with feline lumbosacral disease. Through this process, as a pet owner, I discovered that it's a disease technicians need to be better informed about.

History

Pollux is a male, neutered, 14-year-old, gray, domestic longhaired cat that is missing his left eye and has a stumped tail. He had a two-year history of stiff hindlimbs, an inability to jump, and sensitivity when his hind end was touched. All of these signs slowly worsened over time. Pollux's appetite had steadily decreased, but he was still eating fairly well.

Jennifer Keefe and Pollux

I assumed Pollux had arthritis partly because of his habit of jumping off of a second-story porch, which had once resulted in an inguinal hernia. Initially, Pollux was treated for his current clinical signs conservatively with the oral supplements glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate. This amounted to the contents of one Cosequin For Cats (Nutramax Laboratories) capsule mixed in his food daily. Radiographs were not obtained at this time because of Pollux's temperament, which would have necessitated heavy sedation.

Further evaluation was pursued when it appeared the glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate were not helping and some muscle atrophy was noticed.

Feline disk disease at a glance

Initial evaluation

A board-certified surgeon initially evaluated Pollux. He received sedation and orthopedic, neurologic, and radiographic examinations. Physical examination results revealed generalized muscle atrophy that was visibly worse over both hindlimbs. No evidence of patella luxation, cruciate disease, or hip osteoarthritis was present. The remainder of the orthopedic examination results were normal. The neurologic evaluation revealed consistent caudal lumbar or lumbosacral pain on direct palpation and tail manipulation. There was no evidence of proprioception (see "Glossary" for definitions of italicized words throughout the article) deficits or other reflex deficits of the hindlimbs. Pollux appeared to have both fecal and urinary continence.

Glossary

Radiographs revealed marked narrowing of the lumbosacral (L7-S1) intervertebral and intervertebral foraminal spaces. There also was marked ventral spondylosis deformans of the L6-L7 and L7-S1 regions and mild osteolytic changes to the adjacent vertebral endplates (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis list included degenerative lumbosacral stenosis, a spinal compressive lesion from a disk protrusion or neoplasia, diskospondylitis, or another nonspecific orthopedic or neurologic cause for the pain.

1. A lateral radiograph of the lumbar spinal region. Marked narrowing of the lumbosacral (L7-S1) intervertebral and intervertebral foraminal spaces is seen. There are also marked ventral spondylosis deformans of the L6-L7 and L7-S1 regions and mild osteolytic changes to the adjacent vertebral endplates (white arrows).

Palliative medical therapy was started with a combination of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) and gabapentin, an anticonvulsant that can help with neurogenic pain when given in lower doses as an adjunct medication. Pollux was given 2.5 mg/kg of gabapentin orally twice a day and meloxicam at a loading dose of 0.1 mg/kg orally once a day for three days and then at a maintenance dose of 0.025 mg/kg orally two or three times a week. Note that though these drugs are commonly used with success in such cases, it is extralabel use. Gabapentin is not FDA-approved for use in dogs and cats, and meloxicam is only FDA-approved for injection in cats. Pollux was much more comfortable and active initially, but the clinical signs recurred several months later.

Subsequent evaluation

Pollux did not come running for breakfast one morning, which was unusual. I found him curled up in a corner, and he screamed when touched. The gabapentin dose was increased to 5 mg/kg twice a day, and Pollux began receiving sublingual buprenorphine (0.015 mg/kg up to four times a day). It took about a day and a half for these medications to become effective. An attempt was made to add methocarbamol to the regimen since Pollux's hindlimbs were still stiff, but it induced vomiting and was discontinued.

Results from a repeat radiographic examination showed that the narrowing at the lumbosacral space had progressed. The radiographs also showed that Pollux was constipated, which was thought to be related to the opiate medication, decreased water intake, and potential pain in the rectal or lumbar area. Although the buprenorphine had slowed Pollux's gastrointestinal tract considerably, multimodal pain management (an NSAID, gabapentin, and a partial agonist opioid) helped get Pollux's pain under control quickly. Giving only one medication would likely not have controlled the pain. The results of a complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry profile, thyroxine assay, and urinalysis were all normal.

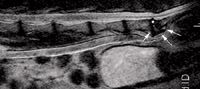

Because of the probable need for advanced imaging to rule out certain neurologic causes, Pollux was presented to a neurologist for evaluation. The neurologist recommended and performed additional diagnostic tests including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a cerebrospinal fluid tap and analysis. The MRI findings included marked effacement of the spinal canal at L7-S1 due to a combination of dorsal protrusion of the intervertebral disk and osseous proliferation causing stenosis (Figure 2). There appeared to be sufficient room for the pelvic nerves to run through, which explained why there was no loss of neurologic function, though it did appear the attenuation was enough to cause neurogenic pain. There was no obvious evidence of a neoplastic process, and with the degree of spondylosis present, it was presumed that the lesion was more likely a variance of degenerative lumbosacral stenosis. The cerebrospinal fluid tap revealed only minor changes consistent with mild inflammation. No infectious or neoplastic agents were identified.

2. A sagittal T2 MRI image. There is marked effacement of the spinal canal at L7-S1 due to a combination of dorsal protrusion of the intervertebral disk (above white asterisk) and osseous proliferation causing stenosis (white arrows).

Treatment

Additional medical therapy and surgical intervention were discussed as treatment options. Surgical options for the treatment of degenerative lumbosacral stenosis include a combination of dorsal laminectomy, diskectomy (removal of an intervertebral disk), foraminotomy (widening of the opening that the nerve runs through), or surgical separation or fusion depending on the degree of disease present.

Because of the mild abnormal changes to the vertebral endplates, the neurologist suggested trying a six-week course of antibiotic therapy first in case the cause was, in fact, infectious. Although it is rare in older animals, it was possible that Pollux had diskospondylitis instead of diskospondylosis. Diskospondylitis is an infection that can be treated effectively in some patients with antibiotic therapy alone, though some patients will still need decompressive surgery because of the considerable reaction that occurs at the intervertebral space. It appeared doubtful that this was the cause since Pollux had been symptomatic for more than two years, the CBC results showed no increase in white blood cells, and the imaging and other diagnostics did not seem to support an infection.

Therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (62.5 mg orally twice a day) was still a viable option because the body can isolate the affected area and show no signs of a disseminated infection. Initially, oral medication was administered, but eventually, Pollux was switched to a compounded transdermal amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (0.3 ml twice a day) because of nausea caused by the oral administration. The efficacy of transdermal antibiotic therapy is questionable, but the clinical signs associated with the oral administration were not an option, and neither was long-term therapy with a fluoroquinolone (e.g. enrofloxacin) because of concern about acute, irreversible blindness.

Follow-up

After six weeks of therapy with the transdermal amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, Pollux's clinical signs continued to dissipate. His previous energy level returned, he never needed pain medicine again, and the generalized muscle atrophy reversed to some degree, He was euthanized because of an unrelated illness this past January at the age of 17.

Although there are still many unanswered questions regarding Pollux's original diagnosis, his marked response to therapy seems to indicate a possible infectious cause after all. I am just glad that my little buddy had a good, pain-free quality of life.

Discussion

Many veterinary professionals are not aware cats can get certain forms of disk disease, and feline disk disease is often overlooked in veterinary medicine. The differential diagnoses for a cat with hind end pain usually include neoplasia (spinal lymphoma, osteosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma invasion) and thromboembolic disease, which often have poor prognoses. In both cats and dogs with the primary clinical sign of neurogenic pain, the prognosis for lumbosacral disease is often good with decompressive surgery and, in some cases, medical management, though the chance for recurrent pain is higher in medically managed patients.

Other presenting signs for lumbosacral stenosis not seen in this case include neurologic deficits such as fecal or urinary incontinence due to lower motor neuron lesions and weakness or neurologic deficits of the hindlimbs.

Pollux's case also highlights the potential benefits of using adjunctive pain therapy. Although some veterinary professionals know of gabapentin only as an anticonvulsant, it is used as an adjunct drug for neurogenic pain with a dose range of 1.25 to 10 mg/kg. It is usually given orally at a dosage of 3 to 5 mg/kg two to three times a day. Not many clinical studies have been conducted about this medication in veterinary patients, but it appears the only adverse effect is sedation. However, it should be dosed cautiously in patients with renal disease as it is eliminated primarily through the kidneys. Also, it should be administered two hours before or after antacids are administered because they affect absorption.

Conclusion

Hopefully Pollux's case has shone a spotlight on another differential diagnosis in older cats to rule out before casting them into the arthritic pet file. It is important for us technicians to be aware of this disease and its treatment options so we can be an integral part of our patients' diagnostic and treatment plans. We could dramatically change a cat's life for the better—or even save it.

RECOMMENDED READING

1. Jaeger GH, Early PJ, Munana KR, et al. Lumbosacral disc disease in a cat. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2004;17:104-106.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Gena Silver, DVM, MS, DACVIM (neurology), for her care of Pollux and Brett Wood, DVM, MS, DACVS, for his care of Pollux and especially for helping edit this article.

Jennifer Keefe, CVT, VTS (ECC, anesthesia), has 14 years' experience working in veterinary emergency and critical care in southern New Hampshire and eastern Massachusetts.