Eliminating Canine Rabies From the Western Hemisphere

Much progress has been made in eradicating this deadly disease, but roadblocks remain, experts say.

In a review article published last month, Andres Velasco-Villa, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues from around the world highlighted major milestones critical to eliminating dog-transmitted rabies in people and outlined impediments to achieving this goal.1

“We tried to present the information in a way that is accessible and raises awareness among key players in government, policy makers, and other stakeholders, so that they can make information-based investments to eliminate the dog-maintained rabies viruses, and to prevent rabies virus re-introductions from other natural sources, which requires sustained rabies herd immunity in dog populations,” Dr. Velasco-Villa said in an interview with American Veterinarian®.

Background

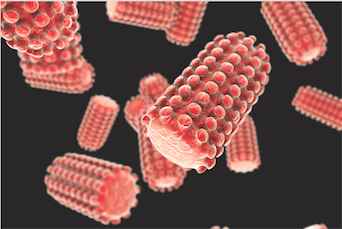

Rabies is caused by viruses in the genus Lyssavirus of the family Rhabdoviridae. Rabies is the prototype species of the genus and causes disease in nearly all terrestrial mammals. The virus is transmitted from animals to people through bites or scratches, typically when saliva from the infected animal comes into contact with human mucosa or fresh skin wounds.

Rabies virus has a broad host range. Throughout its evolutionary history, the virus has established itself in a wide variety of species of bats and terrestrial carnivores, allowing it to circulate in independent maintenance cycles. “This host plasticity alone makes rabies eradication largely unfeasible,” Dr. Velasco-Villa said. However, he added that the mode of transmission of rabies virus makes it highly unlikely that rabies could become pandemic in humans or susceptible mammals, particularly not in the same way that influenza and other airborne RNA virus pandemics arise.

Most cases of rabies in humans are caused by dog bites. However, this deadly disease can be prevented in both dogs and humans by vaccination. Indeed, large-scale vaccination of dogs against rabies has reduced the incidence of the disease dramatically in people in the Western Hemisphere over the past decade.

The Importance of Herd Immunity

According to the study authors, although eradicating dog-main- tained rabies is an attainable goal, it requires permanent elimi- nation of both dog-maintained and dog-derived rabies virus variants. Rabies herd immunity should be maintained above 70% in dog populations to avoid re-introducing the disease from other natural sources such as bats and wild animals, they stressed, and reaching this level could be challenging because of the high reproductive rate of free-roaming dog populations. “Ideally, sustained elimination of rabies from dogs will be feasible only if free-roaming dog populations are controlled,” Dr. Velasco-Villa noted. Thus, programs focusing on complete elimination of this disease in dogs must consider also using humane methods of controlling these canine populations, he added.

Efforts In Latin America

The authors emphasized that, in Latin America, political recognition of canine rabies as a human public health problem was a turning point in the move toward sustainable rabies control and prevention programs. Today, the ministries of health han- dle all these activities, which previously were coordinated and funded by the ministries of agriculture in most Latin American countries. “The new initiative guaranteed sustained budgets for all activities related to rabies control and prevention in dogs, such as mass vaccination, creation and maintenance of a diagnostic infrastructure, construction of anti-rabies centers, support for dog population—control activities, and educational outreach,” the authors wrote.

In addition to culling, surgical spaying and neutering have been used during mass vaccination campaigns in Latin America. Hormone-based vaccine-induced contraception also has shown promise in these areas. In this strategy, a contraceptive hormone component is incorporated into new-generation, single-dose rabies vaccines. “Single-dose vaccines comprise a highly attenuated (completely avirulent) replication-competent rabies virus, which has been genetically modified to become more immunogenic and carry a contraceptive component,” Dr. Velasco-Villa said.

These types of vaccines will both reduce the number of doses needed to produce immunity and prevent the need to use surgical or chemical population-control measures. According to Dr. Velasco-Villa, if an oral formulation can be developed, the administration and distribution costs will decrease. “Furthermore, this type of approach will make vaccination and dog population control a more affordable and humane alternative for resource-limited countries, where free-roaming dog populations are largely responsible for the chronicity of the problem,” he said.

Indeed, these intense efforts to eliminate dog-maintained rabies virus variants in Latin America have dramatically reduced the human rabies burden in these countries. From 2005 to 2015, a 98% reduction in the number of rabies cases in dogs contributed to a 96% reduction in the number of rabies cases in people—from 285 cases in people in 1970 to just 3 in 2015.

Challenges to Elminating Rabies

Some of the most significant barriers that hinder complete elimination of canine rabies include “limitation of monetary resources, public health prioritization, uncontrolled free-roaming dog populations, and cultural backlash,” according to Dr. Velasco-Villa. He stressed, however, that educational outreach regarding approaches that encourage more humane treatment of dogs could also help shift negative cultural behaviors that contribute to growing numbers of stray dogs throughout the world.

The authors emphasized that the significant decrease in the incidence of dog-maintained rabies in the Western Hemisphere, along with the nearly zero number of cases in people, could create a false sense of security among public health officials and governments. This could result in canine rabies no longer being considered a public health problem, leading to budget cuts or even elimination of strategic national control programs.

However, the authors stressed, there is a constant risk that epizootics could recur wherever “hot spots” of dog-maintained rabies and large populations of free-roaming dogs exist. In such instances, herd immunity decreases and dog-derived rabies virus variants continue to circulate near naïve dog populations, they said.

“The complete elimination of canine rabies, especially in ‘hot spots,’ requires permanent funding, with governments and people committed to bringing resources and elimination activities to those remote localities where the problem persists,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Parry, a board-certified veterinary pathologist, graduated from the University of Liverpool in 1997. After 13 years in academia, she founded Midwest Veterinary Pathology, LLC, where she now works as a private consultant. Dr. Parry writes regularly for veterinary organizations and publications.

Reference:

- Velasco-Villa A, Escobar LE, Sanchez A, et al. Successful strategies implemented towards the elimination of canine rabies in the Western Hemisphere. Antiviral Res. 2017;143:1-12.