Equine Cushing's disease: Treatment and case discussions (Proceedings)

Management of pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) in equids consists of improved husbandry, including adequate nutrition and limiting competition for feed, body-clipping, dentistry, and appropriate treatment of concurrent medical problems. In addition, specific treatment with the dopamine agonist pergolide can improve quality of life and reverse many clinical signs of the disease in PPID-affected equids.

Management of pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) in equids consists of improved husbandry, including adequate nutrition and limiting competition for feed, body-clipping, dentistry, and appropriate treatment of concurrent medical problems. In addition, specific treatment with the dopamine agonist pergolide can improve quality of life and reverse many clinical signs of the disease in PPID-affected equids. Combination treatment with both pergolide and cyproheptadine, in the author's experience, may also prove beneficial in more advanced cases. For patients with chronic laminitis, appropriate trimming or shoeing and judicious use of analgesic medications is also necessary. Although many nutritional supplements and nutraceuticals have been advocated for use in equids with PPID, none have established data to support their touted benefits. Finally, due to the expense of lifelong medication, a decision of whether or not to treat affected horses with pergolide should be made on a case-by-case basis in consideration of the client's goals for the patient.

Husbandry and nutritional considerations

Management of equids with PPID initially involves attention to general health care along with a variety of management changes to improve the condition of older animals. In the earlier stages of PPID, when hirsutism may be the primary complaint, body-clipping to remove the long hair may be the only treatment required. Next, since many affected animals are aged, routine oral care and correction of dental abnormalities cannot be overemphasized. In addition, assessment of diet and incorporation of pelleted feeds designed specifically for older equids (e.g., senior diets) should be pursued. In the author's experience, aged horses both with and without clinical signs of PPID can easily gain 50 or more pounds within 3-4 weeks of placing them on a Senior feed.

Sweet feed and other concentrates high in soluble carbohydrate are best avoided (unless that is all that they will eat), especially when patients are hyperinsulinemic, hyperglycemic, or both. Also, affected equids may need to be separated from the herd if they are not getting adequate access to feed. Unfortunately, because the abdomen may become somewhat pendulous, weight loss and muscle wasting in more severely affected animals may not be well recognized by owners. In these instances, measurement of body weight, or estimation with a weight tape or body condition score, are important parameters to monitor during treatment.

Whether or not it is "safe" to allow PPID-affected equids to graze pasture as a forage source remains controversial. Pasture, especially lush spring and early summer pasture, should be considered similar to feeding concentrates high in soluble carbohydrates and many veterinarians recommend that PPID-affected equids NOT be turned out on pasture. In my opinion, it is important to assess the overall condition of the patient. If the horse or pony is overweight and has abnormal fat deposits, supportive of insulin resistance, pasture turn out would not be recommended. Instead, feeding grass hay at 1-1.5% of the body weight daily would be the preferred forage diet and animals that are overweight clearly do not need an additional "low starch" concentrate feed. However, if body condition is somewhat poor, strategic grazing for several hours per day can be a useful way to increase caloric intake and produce weight gain. Again, caution is advised and access to lush spring or early summer pasture should be avoided or at least limited to one or more shorter periods per day, preferably during the early morning hours.

Since the major musculoskeletal complication of PPID is chronic laminitis, regular hoof care is essential to lessen the risk of flare-ups. It is important to emphasize to clients that starting medical treatment for PPID (i.e., pergolide) may not lead to complete resolution of the pain and intermittent hoof abscesses that can accompany chronic laminitis, due to the damage to the laminar bed that has previously been sustained. Further, intermittent use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, primarily phenylbutazone, may be necessary. Although flare-ups of chronic laminitis remain a leading cause for a decision for euthanasia in PPID-affected equids, it also warrants emphasis that a combination of medical treatment for PPID along with regular hoof care can lead to substantial clinical improvement (Figure 1). Finally, because many PPID affected patients may have secondary infections (e.g., sinusitis, dermatitis, and bronchopneumonia), intermittent or long-term administration of antibiotics, typically a potentiated sulfonamide, may be necessary.

Figure 1. Photographs of the front feet of a pony with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction and chronic laminitis: left, initial evaluation (September, 2006); middle, 5-month re-examination (February, 2007); right, 14 month re-examination (November, 2007). Despite a visual appearance to the hoof that may actually seem worse over time (e.g., lower hoof angle after 5 months), a marked improvement in lameness was observed. In addition, hoof conformation was nearly normal after a year of treatment and corrective hoof care.

Medications for treatment of PPID

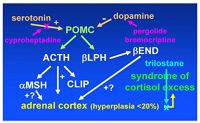

Medications that have been used to treat equids with PPID include serotonin antagonists (cyproheptadine), dopamine agonists (pergolide mesylate), and, more recently, an inhibitor of adrenal steroidogenesis (trilostane) (Figure 2). Cyproheptadine was one of the initial drugs used because serotonin had been shown to be a secretagogue of ACTH in isolated rat pars intermedia tissue. Early indications that cyproheptadine (0.25-0.5 mg/kg, q 24 h) results in clinical improvement and normalization of laboratory data within 1-2 months have been disputed as a similar response has been obtained with improved nutrition and management alone. The margin of safety of cyproheptadine appears to be high as several horses have received twice the recommended dose twice daily without untoward effects. Mild ataxia has been described in some horses treated with cyproheptadine but this has not been observed by this author.

Figure 2. Medications used for treatment of pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) in horses: the dopaminergic agent pergolide is used to replace dopamine lost as a consequence of hypothalamic dopaminergic denervation; cyproheptadine is an antagonist of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that may potentiate secretion of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC); and trilostane, a competitive inhibitor of 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, that may limit cortisol production by the adrenal gland. βLPH = β-lipocortin; βEND = β-endorphin; αMSH = α-melanocyte stimulating hormone; CLIP = corticotropin-like intermediate lobe peptide.

Because loss of hypothalamic dopaminergic innervation appears to be an important pathophysiologic mechanism for PPID, treatment with dopaminergic agonists represents a logical approach to therapy. Pergolide administered in both "high dose" (0.006-0.01 mg/kg, PO, q 24 hours [3-5 mg to a 500 kg horse]) and "low dose" (0.002 mg/kg, PO, q 24 hours [1 mg/day for a 500 kg. horse]) treatment protocols have been reported to be effective. Adverse effects of pergolide may include anorexia, diarrhea, and colic; however, the latter problems are more often associated with higher doses of the drug. Usually, only transient anorexia is recognized during the initial few weeks of "low dose" pergolide treatment and can be overcome by stopping treatment for a couple of days and starting back at half the dose for 2-4 days, slowly increasing to the desired dose.

Trilostane (0.4-1.0 mg/kg q 24 hours in feed), a competitive inhibitor of 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, has been reported to be effective in reversing both clinical signs (primarily laminitis) and abnormal endocrinologic test results in a series of equine PIPD cases. However, horses and ponies in that study received additional management for laminitis and the "improvement" in endocrinologic test results was not overly convincing. In contrast, early attempts at treatment with the adrenocorticolytic agent o,p'-DDD were largely unsuccessful. Because adrenocortical hyperplasia has been recognized in, at most, 20% of horses with PPID, drugs targeting adrenal steroidogenesis would intuitively seem less likely to be successful. However, it is possible that concurrent use of pergolide and trilostane (currently not available in the United States) could produce a greater clinical response than use of pergolide alone.

At present, it is the author's opinion that the initial medical treatment for equids with PPID should be pergolide mesylate at a dose of 0.002 mg/kg, PO, q 24 hours (1 mg/day for a 500 kg horse). If no improvement is noted within 8-12 weeks (depending on season as hair coat changes will vary with the time of year that treatment is initiated), the daily dose can be increased by 0.002 mg/kg (to 2mg/day) with reassessment after 60-90 days. The author typically increases pergolide to a total dose of 0.006 mg/kg (3 mg/day for a 500 kg horse). If only a limited response is observed with 0.006 mg/kg of pergolide and endocrinologic test results remain abnormal, addition of cyproheptadine (0.5 mg/kg, PO, q 24 hours) to pergolide therapy has been effective in a limited number of cases treated by the author. It is important to recognize that the rate of clinical improvement is higher than that for normalization of endocrinologic test results. For example, in a treatment study performed by the author, 13 of 20 pergolide treated horses were reported to have improved clinically while only 7 of 20 had normalization of endocrinologic test results. Thus, it is prudent to regularly measure blood glucose concentration and perform follow-up endocrinologic testing when managing an equid with PPID. The author currently recommends performing an overnight DST (or measurement of plasma ACTH concentration) at least yearly (between December and June in horses in the northern hemisphere) in horses that appear to be stable and 8-12 weeks after a change in medication dose or addition of cyproheptadine). Finally, it is important to remember that, at present, treatment with either pergolide or cyproheptadine remains both empirical and off-label, as pharmacological studies of the drugs have not been performed in equids and no approved drugs are available. Further, although pregnant mares have been treated with the drugs, safety of use during pregnancy has not been studied in equids. Pergolide mesylate is currently only available from a number of compounding pharmacies as the pharmaceutical grade tablets (Permax®) were recently removed from the human market due to development of heart valve problems in a limited number of patients. A major advantage of the compounded products is lower cost; however, pergolide may not remain stable in an aqueous solution (suspension) for longer than 7 days. Thus, it is important to determine how the drug is prepared and dispensed by the compounding pharmacy before specific formulations can be recommended for use.

As with many chronic diseases in the horse, specific nutrient supplementation and complementary or alternative therapies, including acupuncture, homeopathy, and herbal remedies, have been recommended and used in equids with PPID. Both magnesium and chromium supplementation have been advocated for supportive treatment of this condition. Magnesium supplementation (to achieve a dietary calcium:magnesium ratio of 2:1) has been recommended because magnesium deficiency appears to be a risk factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in humans and anecdotal reports suggest that supplementation may help horses with obesity-associated laminitis. Similarly, chromium supplementation is recommended to improve carbohydrate metabolism (specifically glucose uptake) and improve insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. A herbal product made from chasteberry has also been advocated for treatment of PPID. However, the claim was supported with a series of case testimonials in which the diagnosis of PPID was poorly documented and a recent field study demonstrated that this herbal product was ineffective for treatment of PPID.

Prognosis

Once present, PPID is a lifelong condition. Thus, the prognosis for correction of the disorder is poor. However, PPID can be effectively treated with a combination of management changes and medications. Thus, the prognosis for life is guarded to fair. There has been little longitudinal study of equids with PPID but in one report survival time from initial diagnosis to development of complications necessitating euthanasia ranged from 120 to 368 days in four untreated horses. Further, there are numerous anecdotal reports of horses being maintained for several years as long as response to medical treatment was good and close patient monitoring and follow-up was performed. The author has followed a handful of horses treated for PPID with pergolide for nearly a decade and has gained a clinical impression that the drug improves the quality of life but that does not necessarily equate to prolonging life. A recent case series also found that concurrent presence of hyperinsulinemia with PPID was a negative prognostic factor. This finding supports measurement of fasting insulin concentration in the initial evaluation and ongoing management of horses with PPID.

Supplemental readings available on request to the author