Geodes: symbols of inner beauty

If we look below the surface, often we will find that, like geodes, each person is unique. Look into others as well as looking at them. We are certain to find more than meets the eye.

"YOU CAN'T ALWAYS JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER."

During the past two decades, we have analyzed more than a half-million uroliths submitted to the Minnesota Urolith Center. Experience has taught us that we cannot reliably judge their mineral composition by their external appearance.

Photo 1: Geode with an outer surface of chalcedony.

Although evaluation of the outer surface of urinary stones often provides useful information, one must also consider what is beneath the surface in order to obtain reliable diagnostic data. In like fashion, the importance of examining what lies within a patient is the cornerstone of the discipline of internal medicine.

What are geodes?

With this principle of looking beyond the surface, consider the examination of another type of stone, the geode. The word "geode" is derived from the Greek word "geoides" meaning earthlike. Geodes typically are spherical, hollow inside and vary from less than an inch to more than a foot in diameter. They have been found throughout the Earth.

Photo 2: Cross section of the geode described in Photo 1.

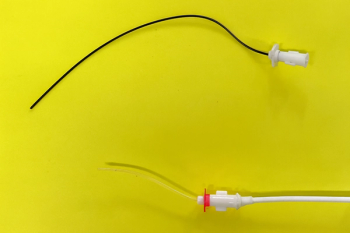

At first glance, geodes often look like ordinary stones that blend into the landscape (Photo 1). Their outer layer, often composed of bland-looking chalcedony, gives no indication of what is concealed within. But if you break them open and examine what is inside, often you will find that their subdued surface conceals eye-catching aggregates of inward-projecting, sparkling and colorful crystals (Photo 2).

Although there are many types of geodes, geologists often categorize them into two groups. One group of geodes are formed in igneous rock, particularly lava. In this group, gas bubbles in molten volcanic rock formed hollow spheres when they were trapped as the magma cooled. Subsequently, when water supersaturated with a variety of elements (especially silica) seeped into these hollow spaces, crystals formed and grew inward from the outer wall of the cavity.

The other group of geodes formed in sedimentary rock. Initially, decomposing organic materials became mineralized with calcite (calcium carbonate). Next, changes in the chemical composition and pH of the water in the sediment resulted in replacement of the outer margin of the calcite concretion with a gelatinous semi-permeable shell of silica.

Further changes in the composition and pH of the water percolating through the shell of silica resulted in dissolution and removal of the inner core of calcite, leaving a hollow cavity. With time, the peripheral gel of silica dehydrated and crystallized to form an outer layer (or rind) of chalcedony (microcrystalline quartz whose crystals are too small to be seen with the naked eye).

Cracks subsequently developed in this outer shell, allowing water supersaturated with a variety of elements to enter the cavity. Precipitation of these elements resulted in the unconstrained inward growth of crystals, starting at the rind and projecting into the hollow center.

The inner appearance of geodes is dependent on the environmental conditions (temperature, pH, etc.) in which they formed, and the types of elements in the water that percolated through them. Precipitation of minerals such as quartz or amethyst transformed the insides of geodes into dazzling formations of crystals. The outward characteristics of such geodes may not catch your attention, but you can't miss their inner beauty (Photos 1 and 2).

Not all geodes contain attractive formations of crystals. For example, minerals protruding from the rind of geodes containing large quantities of chalcedony may have a bumpy cauliflower-like appearance. Geodes filled with unorganized silt from the surrounding sediment are sometimes referred to as mud balls.

Viewing others as geodes

What is the connection between the practice of veterinary medicine and geodes? When you think about it, the personalities of clients, colleagues, neighbors and others that we encounter throughout our lives may be compared to geodes. How so?

On the surface some people may seem to be ordinary, perhaps quiet or shy. Some may seem to have developed a hardened surface (i.e., thick-skinned), perhaps as self-protection from competition, deception or litigation.

But if we look for opportunities to get to know these individuals, we often become aware of inner qualities of their personality that attract us to them. We may discover inner beauty characterized by a warm, kind, understanding and generous spirit. No longer do we consider them as ordinary.

If we look closely, we will often find that, like geodes, each person is unique. Perhaps we can take a lesson from our study of geodes and practice looking into others as well as looking at them. We are certain to find more than meets the eye.

Viewing ourselves as geodes

Another lesson we can learn from examining geodes is the value of examining our inner desires and conscience.

Just as there is a need to examine our physical heart to detect and correct any problems, there is value in examining our figurative heart, which is the seat of our emotions.

As practicing veterinarians, likely we recognize the value of developing and manifesting interpersonal skills that help us make a favorable first impression with others, especially clients.

But if we put ourselves in their shoes and look beyond this surface with the goal of examining our innermost desires, what kind of person would we likely discover? Would we find inner beauty in context of a warm, kind, understanding and generous personality?

As veterinarians, would we find thoughts and actions motivated by an unselfish and compassionate desire to help others in need? Would it be obvious that our conscience is guided by ethical principles? Would we find a heartfelt desire to be patient with our patients, striving to treat them as we would want to be treated?

Or would we find that, as a result of the demands and anxieties associated with our profession and personal lives, we are starting to become half-hearted in our response to the needs of others?

What if we find indications that, figuratively speaking, hardening (mineralization) of the arteries is impairing our oath to "practice our profession conscientiously, with dignity, and in keeping with the principles of veterinary medical ethics?"

What if we find ourselves thinking one thing but speaking another? What if we discover an unhealthy balance between caring about our patients and caring about our profits?

Recall that the types of materials that penetrated the surface layers of geodes during their formative stages influenced whether their inner appearance was attractive or unattractive.

Likewise, the types of ethical and moral values that we allow to guide our thoughts, words and actions contribute to our personalities.

But, unlike geodes, our inner appearance is not etched in stone. If we become aware of undesirable facets of our thoughts, speech or conduct, we can choose to make positive adjustments. The precise prescription for adjustments is dependent on the accuracy and timeliness of our examination.

However, the cornerstone of changes that will help us sustain a whole-hearted commitment to the welfare of living beings, animal and human, is application of the time-tested principle of doing for others what we would have others do for us.

Ultimately, the inner beauty of our personality can only be judged by the conduct it dictates or inspires. dvm

(Adapted from an essay published in JAVMA 224: 1755-1756, 2004.)

by Carl A. Osborne, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM Dr. Osborne, a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, is professor of medicine in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota.

For a complete list of articles by Dr. Osborne, visit

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.