ACVC 2016: Hyperthyroidism in Cats - What You Need to Know

In a lecture at the Atlantic Coast Veterinary Conference, Diane Monsein Levitan, VMD, DACVIM, discussed feline hyperthyroidism.

In a lecture at the Atlantic Coast Veterinary Conference, Diane Monsein Levitan, VMD, DACVIM, discussed feline hyperthyroidism.

The most common endocrine problem of cats worldwide is hyperthyroidism. In the United States, the condition affects 10% of cats over 10 years of age. Veterinarians are detecting the disease at an earlier stage due to routine geriatric blood screening. The actual number of hypertensive cats may be higher because it is difficult to monitor blood pressure regularly in cats and methods are lacking when it comes to keeping the cats calm in order to get accurate readings.

Because hypertension in a hyperthyroid cat is related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, veterinarians should do a cardiac workup. Incidentally, Dr. Levitan has personally found pericardial effusion during cardiac ultrasound in a large percentage of hyperthyroid cats with hypertension. Approximately 70% of the time, the disease is bilateral and affects both glands. Moreover, less than 5% of cats have ectopic abnormal thyroid tissue; however, the most common type of abnormal tissue is functional adenomatous thyroid hyperplasia. Thyroid carcinoma is rare and accounts for just 1% to 2% of cases.

Theories abound regarding why so many older cats develop hyperthyroidism, but there is little hard evidence. Epidemiologic studies point to canned food as a risk factor, and one study points specifically to canned food containing liver, fish, and/or giblets.1 Study authors also note that plastic material in lids or can liners that contain bisphenol-A (a known thyroid disrupter) have also been identified as possible triggers for disease development. Furthermore, it is well known that iodine levels in food also influence thyroid hormone levels.

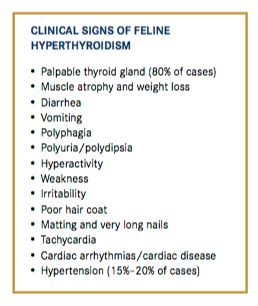

It’s important to note that 10% of cats present with antipathic clinical signs, such as lethargy, anorexia, and dullness. Clinically hyperthyroid cats present with several clinical signs.

Diagnostic Workup

A general diagnostic workup can reveal polycythemia, which Dr. Levitan said is not clinically significant. About 90% of cases of feline hyperthyroidism will have mild to moderate elevations of the enzymes alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, and aspartate aminotransferase, and 20% will have azotemia. However, it’s possible for creatinine levels to be subnormal due to cachexia. Serum cobalamin levels in cats with hyperthyroidism can be low compared with those in healthy cats. One study that analyzed 76 hyperthyroid cats reported 40.8% with subnormal serum cobalamin levels.2 Dr. Levitan recommends supplementation for such patients.

Imaging

Radiographically, 20% to 30% of hyperthyroid cats display cardiomegaly, although less than 5% have radiographic evidence of heart failure. The advanced age of these patients makes comorbidity common, so Dr. Levitan suggests looking past the thyroid for concurrent disease. She has seen several cats with inflammatory bowel syndrome, lymphoma, and other conditions that either presented as if they were hyperthyroid or were also hyperthyroid.

Scintigraphy is the gold standard to identify mild or occult hyperthyroidism because it clearly identifies active thyroid tissue and quantifies disease in mild or occult cases; it also provides valuable information in the diagnosis and evaluation of thyroid carcinoma.

Ultrasound studies are limited by the area examined and by the skill of the sonographer. Inexperienced sonographers can easily mistake a lymph node or blood vessel for thyroid tissue.

Laboratory Testing

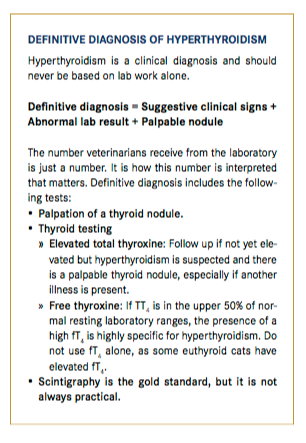

Thyroid testing yields straightforward results when serum total thyroxine (TT4) and free thyroxine (fT4) concentrations are high and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) values are low. In cases of thyroid carcinoma, TT4 numbers are 4 to 15 times higher than normal.

What about the patient that is clinically hyperthyroid but has a normal TT4 and a normal to high fT4? Such cases of occult or subclinical hyperthyroidism are common, but their significance is not yet clear.

Serum TT4 is a very good test for cats, although levels may vary day to day. There is only a 2% rate of false-positive results when the equilibrium dialysis method is used. An elevated serum TT4 level in a cat with clinical signs of hyperthyroidism gives an extremely specific diagnosis. In cases of early hyperthyroidism or concurrent disease, T4 can be in the normal or high-normal range. Suspected cases that have a normal TT4 should be retested on another day. In addition, normal ranges of TT4 can be misleading, as what’s considered “normal” changes with age and with the lab used. Older cats without hyperthyroidism naturally have low or low-normal TT4 levels. Therefore, a high-normal result may indicate hyperthyroidism. Veterinarians should also take into consideration that about 10% of hyperthyroid patients will have normal T4 levels. False-positives, although rare, are seen. Up to 30% of cats presenting with high-normal TT4 concentrations turn out to be euthyroid, even when sometimes coupled with elevated fT4 levels.

Total tri-iodothyronine (T3) is not a very helpful test in cats. Even in mild or occult cases, 80% of patients will have normal results. Serum fT4 is a more sensitive test than TT4 or T3, and the results are less likely to be affected by other factors. However, an elevated fT4 without an elevated TT4, a palpable nodule, or other presenting signs is unlikely to be clinically significant. Because it is a more sensitive test, it is also less specific, and false-positives occur in up to 25% of cases. For this reason, Dr. Levitan suggests always running TT4 and fT4 concurrently at the same laboratory.

Serum TSH is difficult to detect at low levels. Because veterinarians expect low levels in these patients, the test is not helpful unless results are normal or elevated, in which case hyperthyroidism can be removed from the differential diagnosis. Dr. Levitan reminds veterinarians that TSH is a highly sensitive but not very specific test, and 60% to 70% false-positive rates make it of little use.

Treatment

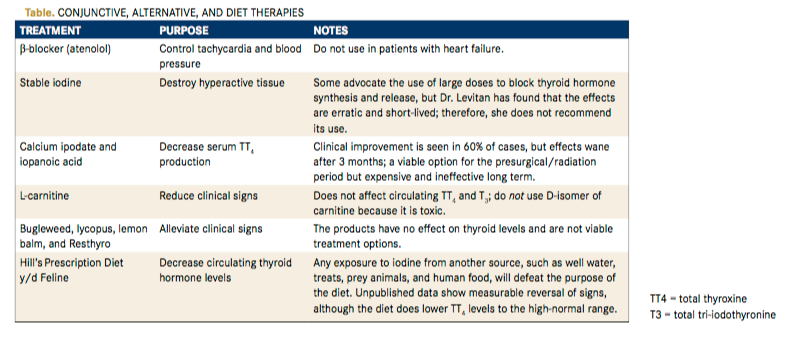

​Generally, therapy for feline hyperthyroidism falls into one of three categories: medical, surgical, or radioactive iodine treatment. Conjunctive, alternative, and diet therapies are also available, some of which are more helpful than others (Table). Management and treatment options should be tailored to the patient’s and owner’s needs and resources, while medical and dietary options should be tried and tested. Radioactive iodine is the gold standard of treatment but may be less than ideal for some patients and prohibitively expensive for some owners.

Medical Therapy

Both methimazole and carbimazole block the synthesis of thyroid hormones. Dosing should start with 2.5 mg divided twice daily; patients should be monitored. The dose may be increased over time as the growing thyroid tissue produces more hormone. The recommended starting dose used to be higher, but experts now advise starting lower and increasing as needed.

These medications are great for stabilizing a patient prior to surgery or radioactive iodine treatment. They can also be used as a trial to look for underlying renal disease. Veterinarians should be careful; if they make the cat hypothyroid, its kidney function will be impaired. Adverse reactions occur in 20% of treated cats and usually develop within the first 3 months of therapy. Uncommon reactions include facial itching and excoriation, blood dyscrasias, and hepatopathy. More frequent reactions are anorexia, diarrhea, lethargy, and vomiting. Carbimazole is metabolized to methimazole; therefore, a cat that has had a reaction to one drug cannot be switched to the other.

Two to 4 weeks after starting treatment, repeat a complete blood count, chemistry screen, urinalysis, and TT4, ensuring that bloodwork is drawn 6 hours after medication has been administered. The dose should be modified to achieve values in the mid-normal range. If hypothyroidism is suspected, a full thyroid panel should be submitted. If a low TT4 and fT4 are coupled with a high TSH, iatrogenic hypothyroidism has occurred and the methimazole dose should be decreased.

Surgery

Thyroidectomy was the ideal treatment for many years. Risks include laryngeal paralysis, voice change, Horner’s syndrome, hypoparathyroidism, and temporary or permanent hypothyroidism. Inadvertent destruction of the parathyroid gland can severely depress calcium levels. Recurrence is possible. Surgical patients require postoperative calcium monitoring and biannual thyroid testing.

Radioactive Iodine

Dr. Levitan expects longer median survival times following radioactive iodine treatment compared with medical treatment. She advises caution regarding where to send patients, however, as some facilities give the same dose to all cats. She recommends using quantitative scintigraphy to tailor the dose to each individual patient. The advantage of radioactive iodine treatment is that parathyroid and atrophied normal thyroid cells are spared, thereby better preventing the potential long-term hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism risk associated with surgery.

Prognosis

​Dr. Levitan is optimistic about the prognosis for hyperthyroid cats with appropriate treatment. She cautions that overtreatment of hyperthyroidism leads to hypothyroidism, the signs of which may not be evident immediately. Veterinarians should continue to monitor patients for life. If hyperthyroidism is suspected, conduct a complete thyroid profile. Findings of low T4 and fT4 along with high TSH levels indicate iatrogenic hypothyroidism.

Dr. Thompson is a small animal veterinarian, animal health executive, editor, and writer. She has held numerous positions with oversight responsibilities for editorial and business direction, including for Veterinary Learning Systems (publisher of Veterinary Technician and Compendium), Vetstreet.com, HealthyPet, and NAVC.

References:

- Peterson ME, Ward CR. Etiopathologic findings of hyperthyroidism in cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2007;37(4):633-645.

- Cook AK, Suchodolski JS, Steiner JM, Robertson JE. The prevalence of hypocobalaminaemia in cats with spontaneous hyperthyroidism. J Small Anim Pract. 2011; 52:101-106.