Identifying and helping cats with inflammatory hepatobiliary disease

Feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease is the second most common cause of liver disease in cats, with hepatic lipidosis being the most common.

Feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease is the second most common cause of liver disease in cats, with hepatic lipidosis being the most common. The disease is classified by hepatic histopathology1 ; terms used to describe it have included suppurative or acute cholangiohepatitis, chronic cholangiohepatitis, chronic lymphocytic cholangitis, progressive lymphocytic cholangitis, sclerosing cholangitis, lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis/cholangiohepatitis, lymphocytic portal hepatitis, and biliary cirrhosis.2 A lack of consistency in terminology has made comparison of reported cases difficult and has hindered clarification of the etiopathogenesis of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease subtypes. In this review, we first discuss the general classifications of the disease and then describe how to diagnose and treat the various types.

CLASSIFICATION

A new classification scheme, proposed by the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Liver Disease Standardization Group, recognizes that feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease largely centers on the biliary tree.3,4 They describe three distinct forms of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease: neutrophilic cholangitis (acute and chronic), lymphocytic cholangitis, and chronic cholangitis caused by fluke infestation.3,4 Unfortunately, since there is not yet consensus within the veterinary community to use this scheme, for this review we use two broad categories of clinically relevant feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease: acute suppurative and chronic nonsuppurative cholangitis. We also briefly discuss lymphocytic portal hepatitis.

Acute suppurative cholangitis

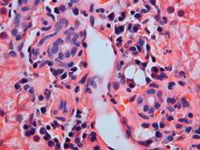

In suppurative cholangitis, hepatic histologic examination reveals neutrophils within the walls and lumina of intrahepatic bile ducts and portal areas with accompanying bile duct epithelial degeneration and necrosis (Figure 1).4 Concurrent periportal parenchymal inflammation is common.4,5 In some instances, suppurative cholangitis occurs secondary to a primary nonsuppurative hepatobiliary disease. In these cases, histologic examination may also reveal lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration of portal areas with varying degrees of bile duct proliferation and fibrosis.

1. Neutrophilic cholangitis. Neutrophils are present within the walls and lumina of the intrahepatic bile ducts and portal areas. Bile duct epithelial degeneration is also present. Microvesicular fatty change can be noted within the hepatocytes (hematoxylin-eosin stain; 400X).

Suppurative cholangitis is thought to be associated with infection.1,5,6 This may be a primary biliary tree infection or an infection secondary to septicemia, dissemination of a chronic infection from another organ system, or treatment with systemic immunosuppressive therapy.1 Many cats with suppurative cholangitis demonstrate disturbances in biliary structure and function that predispose them to ascending bacterial infections.1,5,6 These disturbances can be anatomic, functional, or both. Many of these predisposing conditions have a waxing and waning course or result in subtle clinical signs (e.g. chronic pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease), so clinicians would not necessarily be able to determine whether the process was active. These predisposing factors may result in damage to the biliary tree that then results in abnormalities in biliary structure or function. Predisposing factors include inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis, abnormalities of gallbladder structure and function, choledochitis, biliary parasites, previous biliary diversion surgery, and extrahepatic bile duct obstruction.1,5

The most commonly isolated organisms in cats with suppurative cholangitis are consistent with an enteric origin: Escherichia coli and alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus species, and Actinomyces, Enterobacter, Bacteroides, Klebsiella, and Clostridium species.2 Additional organisms associated with suppurative cholangitis include Toxoplasma species and possibly Bartonella species. In many reported cases, however, a bacterial cause is suspected, but culture results are negative.2 Reasons speculated for the failure to isolate bacteria include 1) lack of anaerobic culture submission, 2) difficulty in growing anaerobic organisms in vitro, and 3) previous antibiotic treatment.1,2

Clinical examination findings

Clinically, cats with suppurative cholangitis tend to be young (median age 3.3 years).1,2,5,6 A predisposition in male cats has been noted. An acute presentation with a short duration of clinical signs (< 5 days) is common.1,2,5,6 History may include anorexia, lethargy, vomiting, and diarrhea. Physical examination findings may include jaundice, abdominal pain, fever, dehydration, lethargy, and, less commonly, hepatomegaly and hypothermia.1,2,5,6

The results of a complete blood count reveal a left shift with toxic neutrophils, with or without a leukocytosis, in about 30% of cases.1,2 Moderate increases in serum alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) activities are frequently noted.1,2,5 ALT activity is more markedly elevated in cases with concurrent extrahepatic bile duct obstruction. Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity is generally mildly increased except in cats with concurrent extrahepatic bile duct obstruction or pancreatitis, in which marked increases occur.1 Increases in bilirubin are typically mild to moderate, but may be dramatic with accompanying extrahepatic bile duct obstruction.

Chronic nonsuppurative cholangitis

Nonsuppurative cholangitis, the most common form of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease, encompasses several reported histologic descriptions, including lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis, lymphocytic cholangitis, progressive lymphocytic cholangitis, and sclerosing cholangitis. It is difficult to determine whether these histologic descriptions represent different diseases or stages of a single progressive disease process. For ease of discussion, we consider three distinct histologic forms: lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis, lymphocytic cholangitis, and chronic cholangitis due to fluke infestation.

Lymphocytic-plasmacytic and lymphocytic cholangitis

Lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis is associated with mild to severe infiltration of portal areas or bile ducts with lymphocytes and plasma cells and lesser numbers of neutrophils (Figures 2A & 2B).1,4 In the lymphocytic variant, the inflammatory cells are predominantly lymphocytes with lesser numbers of plasma cells and neutrophils.4 Bile duct hyperplasia is typically present in both forms. In some cases, bile duct epithelium may become vacuolated and dropout is observed, resulting in a generalized reduction in the number of medium- and small-size bile ductules on histologic samples (vanishing bile duct syndrome).1 Depending on chronicity, varying degrees of portal fibrosis to portal bridging fibrosis or periductal fibrosis are noted.1,2,4,7 In some cases, an onion-skin layering of connective tissue develops around small bile ducts.1 This histologic pattern has been described as sclerosing cholangitis and may represent a progression of lymphocytic or lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis or a separate disease entity.

2A. Lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis. The portal areas and bile ducts are mildly to moderately infiltrated with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and lesser numbers of neutrophils (hematoxylin-eosin stain; 400X).

The development of lymphocytic or lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis may represent tissue response to chronic, nonseptic injury,1 although some cases may represent progression from the suppurative form.2 In the latter case, antibiotics may eliminate the initial bacterial cause, but hepatobiliary damage may continue secondary to self-perpetuating immune reactions to neoantigens released during the initial infection.

2B. Figure 2A at a higher magnification (hematoxylin-eosin stain; 1,000X).

An association between nonsuppurative feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease and chronic inflammatory disease involving the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas has been reported.8 In one study, 39% of cats with cholangiohepatitis had inflammatory bowel disease and mild pancreatitis.8 The term triaditis has been coined for the presence of these three disorders in a single patient. Other studies have noted an association between chronic pancreatitis and cholangitis.5,9 One explanation for this association is that nonsuppurative cholangitis may be one manifestation of a systemic autoimmune disorder. Alternatively, it has been suggested that chronic vomiting secondary to inflammatory bowel disease may increase intraduodenal pressure with subsequent reflux of gastrointestinal contents into the pancreatic duct.1 Since 80% of cats have only one pancreatic duct (which enters contiguously with the bile duct), duodenal reflux perfuses both the pancreatic and biliary systems. The result of this reflux is a low-grade bacteremia or inflammation that can lead to nonsuppurative cholangitis.1 How these disorders relate to one another is unclear at this time. Theories remain largely speculative, and the exact cause of nonsuppurative cholangitis remains elusive.

Lymphocytic cholangitis may represent a lymphoproliferative or neoplastic condition.1 A rare form of primary hepatic lymphosarcoma has been described in people in which small lymphocytes are the predominant cell type.1 It remains to be determined whether some cats with lymphocytic cholangitis have a similar syndrome.

Clinical examination findings. Cats with the lymphocytic or lymphocytic-plasmacytic form present with similar clinical signs.1,2 Most cats are middle-aged or older. But in one study, 14 of 21 cats with progressive lymphocytic cholangitis were less than 4 years of age.10 There is no sex predisposition.1 Commonly, cats have been ill for more than two months, often with a waxing and waning course of clinical illness. Signs are subtle and may include vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and, rarely, anorexia and lethargy.1,2 Some cats may have surprisingly good appetites and appear clinically like cats with hyperthyroidism.1

On physical examination, most cats have hepatomegaly and may be jaundiced.1,2 With the exception of one report, cats rarely present with ascites.10 Cats may develop a fat malabsorption that leads to a vitamin K deficiency and, rarely, to steatorrhea. They may have acholic stools due to decreased fecal bilirubin metabolism.1

Clinicopathologic features are fairly consistent among cats with lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis or lymphocytic cholangitis. All have variable increases in serum liver enzyme activities, and some cats have hyperbilirubinemia. Cats with the lymphocytic variant may have a lymphocytosis and hyperglobulinemia.1,2,10

Chronic cholangitis secondary to liver fluke infestation

On histologic examination, liver biopsy samples from cats with chronic fluke infestation exhibit severe ectasia and hyperplasia of bile ducts and severe concentric periductal fibrosis.3,4 A mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and variable numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils is frequently present in portal areas.4 Eosinophils on a liver biopsy sample may be suggestive of liver fluke infestation because they are rarely seen in other types of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease.4 Concurrent periductal inflammation and edema and bile duct intraluminal neutrophilic exudates, adult flukes, and operculated eggs may be noted. 4

Clinical examination findings. Affected cats often have traveled to tropical areas, but infestation in cats from the continental United States (southern Florida, Illinois) has been reported.11-13 Infestation results from ingesting the second intermediate host (reptile or amphibian) in the fluke life cycle.11-13 Most infestations are caused by flukes of the family Opisthorchiidae (genus Opisthorchis and Metorchis), but infestations with Clonorchis sinensis, Platynosomum fastosum, and Platynosomum concinnum have also been reported in cats.3,11 While most cats are asymptomatic, clinical signs associated with heavy infestations include weight loss, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, hepatomegaly, and abdominal distention.11-13 Clinicopathologic data may include peripheral eosinophilia and evidence of cholestasis. Fluke eggs may be detected on fecal examination through direct smears and routine fecal screening procedures.11-13

Lymphocytic portal hepatitis

Lymphocytic portal hepatitis is characterized by the infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells into portal areas that does not extend into the hepatic parenchyma or involve the bile ducts.14 Lymphocytic portal hepatitis appears to be a common histopathologic lesion in older cats and is distinct from the previously described forms of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease in that inflammation does not involve the biliary tree. In a retrospective study, lymphocytic portal hepatitis was noted in 82% of cats more than 10 years old.14 Most of these cats were asymptomatic for liver disease and had mild and variable changes in serum liver enzyme activity.14

It has been speculated that lymphocytic portal hepatitis is an immune-mediated disease or represents a reactive pattern due to subclinical disease in another organ system, but a nonspecific age-related change cannot be ruled out.2 The WSAVA Liver Disease Standardization Group has questioned the clinical importance of this disorder.4

DIAGNOSIS

Despite certain trends in clinical signs and clinicopathologic data, cats with various forms of inflammatory hepatobiliary disease can only be distinguished based on histologic examination of a hepatic biopsy sample.1,15 Before performing a hepatic biopsy, conduct imaging studies, including abdominal radiography and ultrasonography.

Imaging

Abdominal radiography may reveal hepatomegaly or a liver of normal size.15 In some cases, abnormalities of the biliary tree such as cholelithiasis or biliary tract mineralization may be observed. In rare cases, abdominal effusion or a ground-glass appearance in the right cranial abdominal quadrant may be noted, consistent with ascites and pancreatitis, respectively.

On abdominal ultrasonography, cats with inflammatory hepatobiliary disease have either diffuse changes in echogenicity (hypoechoic most often) or no detectable alterations in the hepatic parenchyma.16 Cats with concurrent hepatic lipidosis may have a diffusely hyperechoic hepatic parenchyma. Biliary abnormalities are seen in about 50% of all feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease cases.16 These abnormalities include gallbladder or common bile duct distention, cholelithiasis, thickening of the walls of biliary structures, and bile sludging.15,16 Common or intrahepatic bile duct distention may occur with extrahepatic bile duct obstruction and can be associated with acute suppurative cholangitis or result secondary to stricture formation from chronic fibrotic biliary or pancreatic disease.2 Prominent portal vasculature was noted on ultrasonography in most feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease cases.16 Ultrasonographic evaluation of the pancreas and intestines may reveal signs consistent with pancreatitis or inflammatory bowel disease.16,17

Hepatic biopsy

A definitive diagnosis of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease requires histologic examination of a hepatic biopsy sample. Hepatic biopsy will confirm an inflammatory cause and permits determination of disease stage (acute vs. chronic), which may have prognostic value. Tissue can also be used for bacterial culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing and special staining techniques (e.g. copper, trichome). Ideally, bile should also be obtained by cholecystocentesis for cytologic examination and bacterial culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing. Cholecystocentesis may be performed by an experienced ultrasonographer via ultrasound guidance or by direct visualization of the gallbladder in cases in which an exploratory laparotomy is elected. Preliminary results suggest that bile may provide a better indication of primary or secondary infection in feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease.18

Before beginning invasive procedures, assess the patient's coagulation status by determining the prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count. Vitamin K1 is routinely given, especially in hyperbilirubinemic animals, 24 to 36 hours before the coagulation profile is performed.

A hepatic biopsy may be obtained by ultrasound guidance (Tru-Cut biopsy with a 16- or 18-ga needle) or by laparoscopy or exploratory surgery (wedge biopsy). Regardless of the technique, optimal evaluation in a relatively stable patient would consist of two or three samples obtained from different liver lobes. Submit the biopsy samples in anaerobic culture medium (aerobes will survive in low-oxygen states) for aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing. In cases in which surgical or laparoscopic sample collection is elected, perform concurrent pancreatic and intestinal biopsy because of the high incidence of concurrent disease in these organs.8,9

Fine-needle aspiration

Fine-needle aspiration may be considered instead of hepatic biopsy in animals with coagulopathies or when hepatic lipidosis or lymphoma is suspected.1 Lipid infiltration in greater than 80% of the hepatocytes or the presence of lymphoblasts can be used to diagnose hepatic lipidosis (primary or secondary) and lymphoma, respectively. Cytologic examination of fine-needle aspirates may also reveal infectious organisms that may be difficult to visualize on histologic sections.1 Keep in mind that fine-needle aspirates will consistently miss hepatobiliary inflammation, so they are inadequate for diagnosing feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease.

TREATMENT

Treating feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease requires identifying and eliminating causative factors, providing supportive care to promote hepatic recovery, and anticipating and controlling secondary complications.

Identifying and treating etiologic factors

In cats with suppurative disease, promptly administer antibiotics that have broad-spectrum coverage for aerobic and anaerobic intestinal coliforms (Table 1).1,2,5,6 In systemically ill animals, good choices include ticarcillin disodium-clavulanate potassium or enrofloxacin or amikacin in combination with ampicillin. Some prefer to add metronidazole for its broad anaerobic spectrum and anti-inflammatory actions.1,2 Less systemically ill cats (lack of neutrophil toxicity, degenerative left shift, neutropenia, hypoglycemia, pyrexia, or hypothermia) may be given either ampicillin or cefazolin alone. Long-term antibiotic therapy can be adjusted based on culture and antimicrobial sensitivity results and should be continued for a minimum of three months.1 In cases of toxoplasmosis, administer clindamycin for four weeks (Table 1).

Table 1: Treatment for Acute Suppurative and Chronic Nonsuppurative Feline Inflammatory Hepatobiliary Disease

In addition to treating underlying bacterial infection, address other predisposing factors for suppurative disease. If abdominal ultrasonography reveals cholelithiasis or extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, surgery for stone removal or decompression of the biliary tract, respectively, is warranted. Survival rates are directly related to prompt definitive treatment and biliary decompression.1

Cats with nonsuppurative cholangitis are generally considered to have an immune basis for their disease, so they are commonly treated with immunosuppressive drugs (Table 1). Thus, make every effort to identify and treat any underlying chronic infections. Long-term management usually involves administering short-acting corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone). In addition to directly targeting a possible immune-mediated cause, corticosteroids may provide symptomatic relief since they are anti-inflammatory and provide some degree of choleresis.1 Concurrent use of metronidazole has been recommended to modulate cell-mediated immune mechanisms involved with chronic inflammation.1 The use of chlorambucil in addition to corticosteroids has been recommended in the lymphocytic variant of the disease.1 The principal adverse effect seen with chlorambucil therapy is myelosuppression, so monitor the patient's complete blood count results for the first few months. The use of low-dose intermittent methotrexate has been suggested in cases in which severe concurrent fibrosis is noted on histologic examination (sclerosing cholangitis).1 Methotrexate can be associated with myelosuppression and gastrointestinal side effects (e.g. anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, intestinal ulceration).

For liver fluke infestations, administer praziquantel for three consecutive days (Table 1), and reevaluate the feces for fluke eggs once the dosing regimen is complete.11-13,19 Achieving a cure is unlikely since some studies suggest that praziquantel does not completely eliminate egg production.19

Providing supportive care

Regardless of the type of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease, supportive care must be provided to protect hepatocytes from further damage and to promote hepatic regeneration. Immediate needs in systemically ill animals include restoring and maintaining of normal fluid and electrolyte balance.1,2

Long-term supportive care includes attention to nutrition. Offer cats a highly palatable, calorie-dense diet to maintain body condition and nitrogen balance. Diets should not be protein-restricted unless renal azotemia (blood urea nitrogen > 80 mg/dl) or overt signs of hepatic encephalopathy (which is extremely rare) are present.1 In patients with concurrent inflammatory bowel disease or pancreatitis, consider a highly digestible, moderately fat-restricted, novel protein diet. Parenteral administration of vitamin B is recommended because chronic liver disease frequently results in cobalamin deficiency and, rarely, thiamine deficiency (Table 2).1

Table 2: Nonspecific Supportive Treatment of Feline Inflammatory Hepatobiliary Disease

In cats that are anorectic for more than three or four days, consider enteral feeding either through a nasogastric tube in severely ill cats or, preferably, through an esophageal tube in cats stable enough for placement. In cases in which an exploratory celiotomy is elected, consider placing a gastrotomy tube or jejunostomy tube (in cases with concurrent acute pancreatitis). If vomiting is present, gastroprotectants and antiemetics are indicated. Famotidine is the H2-blocking agent of choice because it does not interfere with cytochrome P450 systems. A continuous-rate infusion of metoclopramide may be used to decrease nausea and prevent ileus. Concurrent use of a serotonin antagonist such as dolasetron or ondansetron may be required if nausea is not controlled.

Antioxidants such as alpha tocopherol (vitamin E) and S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) may also be beneficial in patients with feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease to scavenge free radicals that may be involved in perpetuating hepatocyte damage (Table 2). SAMe has been shown to modulate inflammation, promote cell replication and protein synthesis, exert cytoprotective effects, and promote sulfation and methylation reactions; it is also an important precursor of intracellular oxidants, including glutathione.20 Low glutathione concentrations are common in feline inflammatory liver diseases.21 Inadequate hepatocellular glutathione concentrations make the liver more susceptible to oxidant damage.21

In some cases of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease, especially those cats with evidence of cholestasis in the absence of bile duct obstruction, ursodeoxycholic acid is recommended to increase bile flow (Table 2). Additional beneficial effects of ursodeoxycholic acid may include immunomodulatory properties and suppression of hepatocellular apoptosis.1

Identifying and treating secondary complications

Secondary complications of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease include coagulopathy, bacterial infection, extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy (Table 3).

Table 3: Treatment of Feline Inflammatory Hepatobiliary Disease-Associated Complications

Coagulopathy

Feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease may result in coagulopathy secondary to decreased synthesis of clotting factors and impaired vitamin K absorption. Initiate empirical vitamin K1 therapy in all cases before any invasive procedures. Vitamin K1 therapy, given subcutaneously, may be continued in hyperbilirubinemic cats every 14 to 21 days. Overdosing vitamin K1 may cause hemolytic anemia associated with Heinz body formation.1 In cases in which decreased synthesis of clotting factors is suspected (elevation in prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, or both) consider administering fresh frozen plasma, or, if the cat is also anemic, performing a fresh whole blood transfusion.

Bacterial infection

People with hepatobiliary disease are predisposed to bacterial infection because of impaired Kupffer cell function, decreased neutrophil function secondary to complement deficiency, and bacterial translocation due to portal hypertension. It is thought that some of these same predisposing factors may make cats with inflammatory hepatobiliary disease more prone to bacterial infection. In most cases, prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is indicated once a diagnosis is made. Patients with acute suppurative cholangitis are at a higher risk of developing sepsis and should be monitored closely for 1) an acute change in body temperature (increase or decrease); 2) the onset of abdominal pain; 3) the development of a neutrophilia, neutropenia, or a monocytosis; 4) a sudden increase in serum bilirubin concentration; or 5) an acute onset of hypoglycemia.

Extrahepatic bile duct obstruction

Cats with inflammatory hepatobiliary disease may develop extrahepatic bile duct obstruction due to strictures secondary to chronic biliary inflammation and fibrosis, a predisposition to biliary adenocarcinoma, or extraluminal constriction from pancreatic fibrosis. Consider periodically reassessing the hepatobiliary tree ultrasonographically in cases that are refractory to treatment.

Ascites

Ascites is a rare complication of feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease and is generally indicative of end-stage liver disease with concurrent portal hypertension. Treatment consists of spironolactone and a low-sodium diet.

Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is caused by the inhibition of excitatory neurotransmission secondary to inadequate hepatic detoxification of gut-derived neurotoxins. Hepatic encephalopathy may be present initially or may develop during the course of therapy. Signs include ptyalism, lethargy, depression, stupor, blindness, and ataxia. Treatment consists of lactulose and metronidazole. Adjust the lactulose dose to achieve three or four soft stools a day. Metronidazole decreases gastrointestinal ammonia production by reducing the population of urease-producing bacteria. Protein restriction is not instituted unless medical management is inadequate; it is adjusted to the maximally tolerated amount.

MONITORING

In cases of suppurative cholangitis, treatment is considered successful if biochemical abnormalities normalize within four weeks and the cat is clinically doing well. Ongoing inflammation should be presumed in cases of persistent increases in serum liver enzyme activities or serum bilirubin concentrations, especially in the presence of a neutrophilic leukocytosis.1 In these cases, abdominal ultrasonography, liver biopsy, and bile collection with cultures should be repeated. It is suspected, but not proven, that suppurative cholangitis may evolve into a nonsuppurative cholangitis.1,2 If nonsuppurative inflammation is verified, culture results are negative, and no underlying source of chronic infection is found, treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs is appropriate.1

In cases of nonsuppurative cholangitis, response to treatment may be difficult to assess because of the slowly progressive nature of the disease and subtle clinical signs. A cat is considered to be in remission if it is clinically doing well (good appetite and activity level, good body condition score), its bilirubin and albumin concentrations normalize, and its serum liver enzyme activities are no greater than twice the reference range upper limit. The goal is to taper immunosuppressive therapy to the lowest dose required to maintain remission. Since long-term high-dose corticosteroid therapy predisposes patients to glucose intolerance and diabetes mellitus, periodic blood glucose assessment is recommended. In cases of persistent or progressive increases in serum hepatobiliary enzyme activities or serum bilirubin concentrations, look for potential complications such as secondary hepatobiliary infection, hepatic lipidosis, extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, or hepatobiliary neoplasia. Unfortunately, many cases may only partially respond to corticosteroids alone even when underlying conditions cannot be identified. In these cats, adding SAMe, ursodeoxycholate, or vitamin E may be of some benefit.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis in cases of suppurative cholangitis is good if the underlying infection is treated promptly and all predisposing factors are corrected.1

The prognosis for cats with nonsuppurative cholangitis has not been well-described and is difficult to extrapolate from review of the current veterinary literature. In one retrospective study involving 16 cases, the mean survival time was 29.3 months, but in over half the cases a serious concurrent illness (e.g. feline infectious peritonitis, lymphosarcoma, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus) probably contributed to death.15 Some of the cases were subclinical for liver disease, but because suppurative and nonsuppurative cholangitis were combined in this study, it is unclear what proportion of subclinical cases were nonsuppurative.15 In another study examining 21 cases of progressive lymphocytic cholangitis, survival ranged from five days in four cats to more than six years in six cats.10 However, three of the cats that died within nine months of diagnosis died of conditions unrelated to their liver disease.10 So we can only say that full remission of disease is not obtained in most cases and that a waxing and waning course of illness is likely.

The prognosis for cats with liver fluke infestation is variable and depends on the infective dose (number of flukes ingested) and the risk of reinfection. Most cases are asymptomatic.11-13 The prognosis for severely affected cats is poor.

CONCLUSION

The clinical signs and clinicopathologic data of cats with inflammatory hepatobiliary disease help us suspect the disorder but rarely help us differentiate the types of disease. Abdominal ultrasonography, hepatic biopsy, and bacterial culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing of liver and bile are necessary to obtain a definitive diagnosis and to rule out a treatable underlying cause. While a predisposing cause is generally present in cases of suppurative cholangitis, the cause of the various nonsuppurative cholangitis subtypes remains poorly understood.

Long-term antibiotic therapy is the treatment of choice for suppurative cholangitis. In nonsuppurative feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease, make every effort to rule out an underlying infectious cause before initiating immunosuppressive therapy. Consider concurrent pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease in cases of nonsuppurative feline inflammatory hepatobiliary disease. In all cases, monitoring serum liver enzyme activities and bilirubin and albumin concentrations will allow you to assess response to therapy. Further research is required to investigate the roles of bacteria and immune stimulation in the etiology of nonsuppurative cholangitis in order to improve the prognosis in these cases.

Johanna Cooper, DVM

Cynthia R.L. Webster, DVM, DACVIM

Department of Clinical Sciences

Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

Tufts University

North Grafton, MA 01536

REFERENCES

1. Center S. Diseases of the gallbladder and biliary tree. In: Grant Guilford W, Center SA, Strombeck DR, et al, eds. Strombeck's small animal gastroenterology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co, 1996;874-884.

2. Weiss DJ, Gagne J, Armstrong PJ. Inflammatory liver diseases in cats. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2001;23:364-372.

3. van den Ingh T. Morphological classification of biliary disorders of the canine and feline liver, in Proceedings. Am Coll Vet Intern Med 2003.

4. Charles JA. Histologic classification of cholangitis in cats, in: Proceedings. Eur Coll Vet Intern Med 2002.

5. Hirsch VM, Doige CE. Suppurative cholangitis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983;182:1223-1226.

6. Shaker EH, Zawie DA, Garvey MS, et al. Suppurative cholangiohepatitis in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1991;27:148-150.

7. Gagne JM, Weiss DJ, Armstrong PJ. Histopathologic evaluation of feline inflammatory liver disease. Vet Pathol 1996;33:521-526.

8. Weiss DJ, Gagne JM, Armstrong PJ. Relationship between inflammatory hepatic disease and inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis, and nephritis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996;209:1114-1116.

9. Forman MA, Marks SL, DeCock HEV, et al. Evaluation of serum feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity and helical computed tomography versus conventional testing for the diagnosis of feline pancreatitis. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:807-815.

10. Lucke VM, Davies JD. Progressive lymphocytic cholangitis in the cat. J Small Anim Pract 1984;25:249-260.

11. Beilsa LM, Greiner EC. Liver flukes (Platynosomum concinnum) in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1985;21:269-274.

12. Greve JH, Leonard PO. Hepatic flukes (Platynosomum concinnum) in a cat from Illinois. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1966;149:418-420.

13. Hitt ME. Liver fluke infection in South Florida cats. Feline Pract 1981;11:26-29.

14. Weiss DJ, Gagne JM, Armstrong PJ. Characterization of portal lymphocytic infiltrates in feline liver. Vet Clin Pathol 1995;24:91-95.

15. Gagne JM, Armstrong PJ, Weiss DJ, et al. Clinical features of inflammatory liver disease in cats: 41 cases (1983-1993). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 214:513-516.

16. Newell SM, Selcer BA, Girard E, et al. Correlations between ultrasonographic findings and specific hepatic diseases in cats: 72 cases (1985-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;213:94-98.

17. Baez JL, Hendrick MJ, Walker LM, et al. Radiographic, ultrasonographic, and endoscopic findings in cats with inflammatory bowel disease of the stomach and small intestine: 33 cases (1990-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;215:349-354.

18. Wagner KA, Hartmann FA, Trepanier LA. Bacterial culture results from 251 cases of hepatobiliary disease in dogs and cats (abst), in Proceedings. Am Coll Vet Intern Med 2005.

19. Evans JW, Green PE. Preliminary evaluation of four anthelmintics against the cat liver fluke, Platynosomum concinnum. Aust Vet J 1978;54:454-455.

20. Center SA. S-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe): an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory nutraceutical, in Proceedings. Am Coll Vet Intern Med 2000.

21. Center SA, Warner KL, Erb HN. Liver glutathione concentrations in dogs and cats with naturally occurring liver disease. Am J Vet Res 2002;63:1187-1197.