Identifying malignant oral tumors

Cancerous growths originating in the mouth region may require treatment with a veterinary dentist or oncologist

A tumor is an abnormal mass of tissue that is not inflammatory, does not have physiological function, and arises with no obvious cause from cells of preexistent tissue. A tumor may also be called a neoplasm or neoplastic mass. Oral tumors are the fourth most common tumors seen in dogs, accounting for 6% of all canine tumors and up to 12% of tumors in cats.1 Oral tumors can originate from several sites in the oral cavity, including the tongue, mucosa, gingiva, lips, maxillary, and mandibular bone,2 and they may spread to adjacent cartilaginous tissues and bone. Metastasis can occur within the lungs and regional lymph nodes.2,3

Peripheral odontogenic fibroma (All images courtesy of Jan Bellows, DVM, DAVDC, DABVP, FAVD)

Signs of oral tumors in cats and dogs include halitosis, loss of teeth, anorexia, dysphagia, facial swelling, hemorrhage, sneezing, hypersalivation, oral pain, pawing at the face, lymph node enlargement, weight loss, and swelling or thickening of the maxilla or mandible.2,3 The oral mass may be visible upon oral examination, but oral tumors often go unnoticed by the pet owner until clinical signs are advanced.4 The normal oral anatomy of the dog and cat mouth should be considered when trying to identify an oral mass. Anatomic structures—such as the normal papillae of the tongue, the incisive papilla (located palatal to the maxillary incisors,) the salivary papillae, the sublingual caruncles, and the molar salivary gland in cats that is located lingual to the first mandibular molars—should not be confused with oral tumors.2

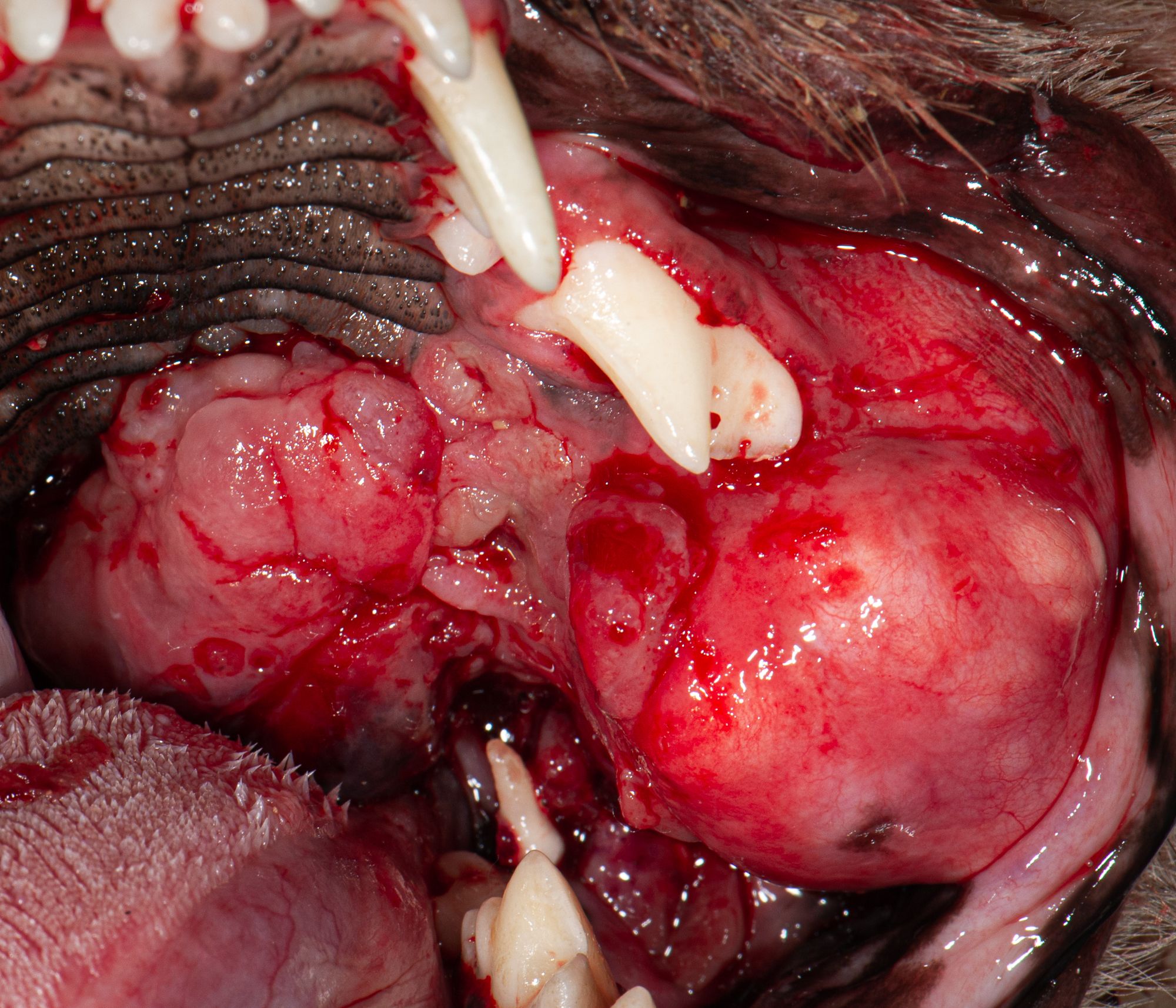

Lobar osteosarcoma

Malignant oral tumors are locally invasive and may metastasize.3 A veterinary dentist and/or oncologist should be considered for treatment that may include surgical excision, chemotherapy, and/or radiation.

A complete history, general physical examination, and thorough oral examination should be performed. General anesthesia may be required for a comprehensive oral evaluation, including palpation of the mass, description of size, location, presence of necrosis, ulceration, pigmentation, firmness, etc.2,3 Diagnostic testing may include a complete blood count, chemistry panel, urinalysis, lymph node cytology, 3-view thoracic radiographs, dental radiographs, CT scans, and MRIs.2,3 An excisional or incisional biopsy is needed to confirm the histopathological diagnosis.1,3

The most common malignant oral tumors found in dogs are malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, osteosarcoma, and fibrosarcoma. The most common malignant oral tumors found in cats are squamous cell carcinoma and fibrosarcoma.1,3

Oral malignant melanoma (OMM) is reported to be the most common malignant neoplasm found in dogs but is rare in cats.1-4 An OMM may appear grayish or brownish-black, ulcerated or necrotic, and firm to friable.4 Although OMM lesions are usually pigmented, 40% may be amelanotic and therefore are pink or red.5 Malignant melanomas occur most commonly on the mucosa and gingiva but may occur anywhere in the oral cavity.4

OMMs occur more often in older, pigmented, male dogs. Miniature poodles, cocker spaniels, and chow chows may be predisposed.2 OMMs are highly invasive to the jawbones and have a high potential for metastasis to the lungs and regional lymph nodes.2 Treatment options for OMM include aggressive and wide surgical resection to prevent recurrence, and adjunctive therapies include radiation therapy and immunotherapy (melanoma vaccine).3,4

The most common malignant oral tumor found in cats and the first or second most common malignant oral tumor found in dogs is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).2,4 It usually affects older cats and dogs, with no sex predilection.3

SCC is commonly located in the premolar or molar regions of the maxilla; premolar region of the mandible; or rostral mandible, palate, or sublingual region at the base of the tongue.2,3 SCC has a pink to red ulcerated, cauliflower-like appearance and bleeds easily or may appear as ulceration with no overt mass.2,4,5 It is a rapidly growing, locally invasive tumor.2

Osteosarcoma

In dogs, SCC is often divided into tonsillar and nontonsillar.4 Higher metastasis and shorter survival time are associated with tonsillar and lingual tumors vs SCC in a more rostral location.5 Cats with SCC often present to the veterinarian for a decreased appetite, decreased grooming, halitosis, ptyalism, and/or weight loss.4 Treatment options for cats are wide surgical excision and/ or radiation or chemotherapy.1 Without clean surgical margins, long-term prognosis for cats with SCC is generally poor.4 It is often difficult or impossible to obtain surgical margins in cats and small dogs, and palliative local irradiation in cats may be considered.3 Dogs tend to adapt better following glossectomy.5 Risk factors in cats may include eating canned cat food or canned tuna, use of flea collars, and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.4,5 Papillary SCC is a less aggressive variant found in both young and old dogs and may present as a gingival mass with a verrucous pink surface.5

Fibrosarcoma (FSA) is the second most common malignant oral tumor in cats and the third most common in dogs.5 FSAs often present as slow growing, firm, flat, diffuse, broad based, and locally invasive.5 Masses usually occur on the maxilla, growing on the palate or lateral muzzle; however, they can also occur elsewhere, such as the mandible.4,5 In dogs, FSA is more common in large breeds with a possible breed predilection for retrievers.5 The treatment of choice is wide surgical excision; however, because FSAs have a high rate of recurrence and that surgery is usually palliative, ancillary radiation is recommended.3,4,5

Osteosarcoma (OSA) may involve the mandible or maxilla; appear as soft or hard, fleshy, red, and friable; and bleeds easily.2,4,5 OSA is locally aggressive, and the metastasis rate of oral OSA is lower than appendicular OSA.3,5 The preferred treatment for oral OSA is radical or wide excision.3

Regardless of the type of oral malignant tumor, early detection and treatment are important for a more positive outcome. The smaller the tumor, the smaller the surgery.

References

- Smith M. Oral tumors. Presented at: 2017 Veterinary Dental Forum; September 14-17, 2017; Nashville, TN.

- Perrone JR, March PA. Common dental conditions and treatments/oral tumors /malignant oral tumors and treatments. In: Perrone JR, ed. Small Animal Dental Procedures for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses, 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2020:134-139.

- Niemiec BA, Dhaliwal RS. Malignant oral neoplasia. In: Niemiec BA, ed. Small Animal Dental, Oral & Maxillofacial Disease: A Color Handbook. Manson Publishing Ltd; 2011:225-235.

- Wingo K. Histopathologic diagnoses from biopsies of the oral cavity in 403 dogs and 73 cats. J Vet Dent. 2018;35(1):7-17. doi:10.1177/0898756418759760

- Reiter AM, Gracis M, Romanelli G, Lewis JR. Management of oral and maxillofacial neoplasia. In: Reiter AM, Gracis M, eds. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Dentistry and Oral Surgery, 4th ed. British Small Animal Veterinary Association; 2018:279-285.