Podiatry proficiency - initial hoof wound assessment can require anesthesia, antibiotics, wire probe and radiographs

Evaluating synovial structures and tendon sheathes requires infusion of sterile saline solution at a point far away from the trauma.

Trauma and injury to the feet of horses is very common because they often encounter foreign objects at pasture. Partially buried wires, cables or other obstacles lurk in deep grass, mud or below the surface of streams and ponds. Running through these areas often results in injury. Horses that kick out while in the barn, trailer or stall can lacerate their distal legs or hooves on metal walls, wood or other unyielding objects. Many important structures can be involved in this type of injury, and these wounds can present special problems that make treatment difficult and challenging for veterinarians.

Regional antibiotic perfusion for a laceration to the caudal pastern allows the delivery of high levels of antibiotics to specific areas of the body, which increases the chances of successful healing.

Dr. Andy Parks, recent inductee into the International Podiatry and Veterinary Hall of Fame and surgeon at the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, reminds veterinarians that hoof wounds heal in the same four phases as wounds in different areas of the body.

"The stages of inflammation, debridement, repair and maturation occur in hoof and foot wounds just as they do in other wounds, though the specific characteristics of the hoof wall can make these various stages harder to identify and follow," Parks says.

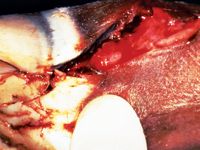

This heel bulb laceration in a young horse continues through the coronary band and involves the navicular bursa, resulting in a poor prognosis.

Correct treatment and monitoring of wound progression, however, is necessary for optimum healing.

Laceration to the palmar/plantar aspect of the pastern and heel bulbs is a commonly occurring event. Damage to the digital synovial tendon sheath, deep digital flexor tendon, proximal and distal interphalangeal joints, and navicular bursa all can occur with injuries to this anatomical area. Involvement of any of these structures greatly worsens the prognosis for recovery and return to function. Therefore the first step in management of hoof or foot wounds in the horse is to perform a thorough examination of the injury. This examination may require local or regional anesthesia in order to fully access the damage to deeper structures. Use of a soft flexible wire probe can be helpful in determining extent and direction of penetrating wounds. Radiographs sometimes are needed to evaluate the underlying bone or collateral cartilage of the hoof. Lavage with a polyionic saline solution can be helpful in cleaning the area and determining the type and extent of injury. Dirt, debris and severely damaged tissue should be removed, taking caution to avoid being overzealous or too aggressive in such debridement. Removing too much tissue might damage sensitive deeper structures and actually slow wound healing.

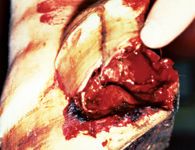

This severe incomplete hoof wall avulsion is an example of how the hoof wall can fracture with trauma. The hoof wall fragment remains attached along one side. Many deeper structures can be involved, including the collateral cartilage, deep digital flexor tendon and distal interphalangeal joint. A complete examination, including joint lavage, will be necessary to assess the extent of the damage and the prognosis.

Infection control

Mild antibiotic solutions may be used to flush and clean the wound, but Parks cautions against using strong products, such as iodine scrubs and solutions because iodine itself can coagulate protein and damage deeper tissue in the hoof. Parks advocates the use of no stronger than 0.1 percent to 1 percent povidone iodine or 0.05 percent chlorhexadine solutions. The evaluation of synovial structures and tendon sheathes requires the infusion of sterile saline solution at a point far removed from the trauma. If the saline solution is noted to be leaking from the wound, then the joint or tendon sheath has been compromised and should be considered infected. If the infused saline is not seen leaking from the original injury, then no damage to the joint or tendon sheath is suspected.

If the joint or tendon sheath is determined to be infected, then it should be lavaged initially with large volumes of saline, and this treatment should be continued every-other day. Amikacin, a potent antibiotic, can be added to the flush solution, and regional antibiotics can be perfused into the area in question, which further raises antibiotic blood levels. This treatment should be continued until joint-fluid analysis or clinical signs indicate no further infection.

dvm Newsbreak

All clinicians agree that primary closure of traumatic wounds is the best treatment option. Cleaning, suturing and bandaging a wound generally produces the best long-term repair. Unfortunately, that approach is not always possible. Excessive tissue loss, infection or instability of the repair can prevent primary closure in some foot wounds. These wounds can respond more favorably to debridement and immobilization. Cleaning the wound and removing any damaged tissue is the first step. Because some tissue can retain good blood flow and will respond over time, it is usually better to proceed slowly and to take less rather than more tissue.

If primary closure is not possible, then granulation or second-intention healing will allow the wound to fill in slowly over time. Fibrosis, scarring with loss of mobility and poor cosmetic appearance, are possible complications of second-intention healing. Cold hosing, hand walking and appropriate bandaging can help this type of treatment succeed.

Stabilization of hoof and heel injuries is very important, and the proper application and monitoring of bandages or cast material is crucial for healing success. Parks says a hoof cast placed on the horse under standing sedation creates a more normal hoof angle and axis, and it is associated with better healing. Drs. Pabareiner, Jarvicek, Honnas and Crabill of the Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine reported on 101 cases of heel bulb lacerations in the horse at the 2004 American Association of Equine Practitioners annual meeting. Using the techniques of lavage, debridement, antibiotics and immobilization, they reported that 56 of 65 (77 percent) of the horses in their study were able to return to their intended use after healing. So these principles are considered the standard for care of this type of equine injury.

Traumatic abrasions

Rope burns or traumatic abrasions caused by the interaction between skin and rope are possible, but they appear to be a much less common cause of injury in the horse. This might be because many more owners and trainers have accepted the need to train their horses properly rather than the previous mentality that insisted that the horse be "broken" and made to be submissive and obedient.

This "gentling" process often involved tying up a leg or tying the horse up closely to a pole. Such practices often resulted in traumatic abrasions to the back of the lower leg, pastern or foot, and while this type of injury is much less common currently, cases do still occur. These wounds can be evaluated just like lacerations or other types of skin injuries and a first-step assessment should attempt to determine if deeper structures are involved. Cleaning, lavage and the placement of support bandages on these wounds is often enough to stimulate granulation tissue and promote healing. Correct physiotherapy can lessen the scarring that often occurs following the healing of rope injuries.

Overall, horses seem to be very adept at injuring themselves, and the means and methods they use to do so is astonishing. A familiarity with and knowledge about the various types of equine wounds is necessary for all clinicians, and treatment plans for theses wounds should include the major principles of lavage and evaluation followed by debridement and antibiotics. Finally, use of immobilization to achieve wound closure and healing should provide horses with optimum chances for successful return to use following injury.

Dr. Marcella, a 1983 graduate of Cornell University's veterinary college, was a professor of comparative medicine at the University of Virginia. His interests include muscle problems in sport horses, rehabilitation and other performance issues.