Purdue 2017: Practical Tips for Avian Radiography

Radiographs are integral to the diagnosis of many conditions in pet birds, but obtaining high-quality images can be difficult in these species.

Obtaining good-quality radio-graphs of sick birds can be a challenge, according to Steve Thompson, DVM, DABVP (Canine and Feline Practice), clinical associate professor of small animal community practice at the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine in West Lafayette, Indiana. Dr. Thompson heads the community practice elective block for fourth-year veterinary students and treats a variety of pets, managing a daily caseload that includes such exotics as parrots, bearded dragons, snakes, and hedgehogs.

Presenting at the 2017 Purdue Veterinary Conference, which was held on the Purdue University campus, Dr. Thompson provided an overview of avian radiography and shared tips to help veterinarians overcome some of the challenges they face when radio-graphing sick pet birds.

Common Uses of Radiography in Birds

Radiography plays various roles in avian practice in addition to its use in assessing orthopedic trauma. “It is a valuable part of the sick bird workup,” Dr. Thompson said, “and can be used to evaluate the coelomic contents because digital cloacal examination provides only limited clinical information in smaller birds and might not be possible in very small birds.” Radiography can also help veterinarians assess air sac clarity in dyspneic birds, he added, because physical examination and auscultation of the lower airways may be limited in these patients.

Obtaining Good-Quality Radiographs

Appropriate patient positioning is critical to obtain diagnostic-quality radiographs of pet birds, Dr. Thompson said. Because manual restraint of birds can be a challenge, he advised veterinarians to consider sedating or anesthetizing avian patients to accomplish this.

Sedation

Although the use of inhalation anesthesia was once considered standard procedure in veterinary medicine to restrain birds for radiography, sedation is now more commonplace and is considered safer than general anesthesia. However, because a sedated bird can still move, Dr. Thompson reminded veterinarians to use the help of technicians to achieve correct positioning.

He stressed that the risks associated with sedating birds can be mitigated by several means: careful patient selection, appropriate drug selection and dosing, and proper monitoring of the sedated patient.

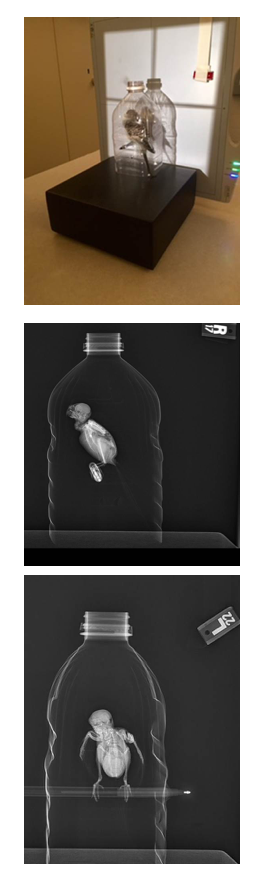

A 2.5-year-old female budgie presented for 3 days of progressive inactivity and fluffed feathers. To obtain radiographs, the bird was placed inside a plastic bottle with a pen used as a perch (top). Horizontal beam radiographs were obtained in the right lateral (middle) and anteroposterior or ventrodorsal (bottom) views.

The opioid analgesic butorphanol is currently considered the most useful agent of its class for birds, Dr. Thompson said. Doses used for birds are much higher than those used for dogs and cats, and start at 0.5 to 1 mg/kg, although some species like Amazon parrots require doses of 2 to 3 mg/kg, typically administered intramuscularly in the keel.

The benzodiazepine midazolam can be a beneficial adjunctive therapy, he noted, allowing reduced doses of butorphanol when the 2 drugs are used in combination. Midazolam helps to reduce anxiety, and its dose in birds ranges from 0.2 to 0.5 mg/kg, also administered intramuscularly. Intranasal dosing is another option with midazolam.

Both drugs can be combined in the same syringe and given as a single injection, or they can be administered separately, starting with midazolam. If veterinarians choose to administer the drugs separately, Dr. Thompson advised that “if after 5 minutes you don’t see any effect, either give a higher dose of the first drug or add in the second drug.”

He reminded veterinarians that sedation is variable across patients. Typically, onset of sedation is rapid and occurs within 2 to 3 minutes, he said. However, its duration may last anywhere from just 20 minutes to 2 hours.

Although sedation has now replaced isoflurane masking techniques as the preferred method to calm a pet bird when performing diagnostic procedures, Dr. Thompson said that if veterinarians choose to use isoflurane anesthesia, they should use nonrebreathing systems because of the small size of these patients. He discussed using a clear plastic bag, a clear syringe case mask, or a small nose cone, which may necessitate covering the bird’s entire head. He also advised veterinarians to provide supplemental oxygen via mask or flow, even to sedated birds, especially in cases of uncertain diagnosis or those involving trauma.

Positioning

Dr. Thompson noted that lateral and ventrodorsal radiographic views are typically used in avian radiography, just as they are in dogs and cats, with the right lateral view being used routinely. He advised veterinarians to pull the bird’s wings and legs away from the body to improve visualization of the coelom. “Dorsal extension of the wings on the lateral is often compromised in pet birds that don’t routinely fly and may have reduced range of motion of the shoulder,” he said. But he warned against forcing or over-extending the humerus because this can be painful or cause rotation on the lateral view.

He emphasized the importance of always following the same procedure for the down extremity. Staff should always either position the downside leg forward (right leg and wing for a right lateral view) or use the “left is left behind” technique (positioning the left wing and left leg caudally) when taking left or right lateral views.

To help stabilize the humerus for positioning, Dr. Thompson suggested that veterinarians use lightly adherent tape that is less likely to adhere strongly to the feathers and thus prevents feather plucking when the tape is removed. Using a clear plastic plate or board will allow the bird to be positioned on a mobile plate when repeat radiographs are needed to improve positioning, or if the technique needs to be changed to improve the radiograph, he said.

Radiography of Dyspneic Birds

Dyspneic birds are a particular challenge, Dr. Thompson said. He noted that these patients are now routinely examined initially with neither sedation nor anesthesia. He recommended allowing dyspneic birds to sit on a perch in a clear container that limits flight but allows use of the cross-table horizontal beam radiographic technique. However, he added that some dyspneic birds may require sedation to calm them. Butorphanol and midazolam can help to reduce the anxiety associated with the dyspnea and relax the bird. This can be less stressful to the patient than either handling or the proximity of many people.

The horizontal beam technique is simple, Dr. Thompson said, and “tells us a lot about a dyspneic animal before we even have to touch it.” However, evaluating air sacs is a major limiting factor of this technique, he said. Nevertheless, he noted that although air sac detail is severely compromised with the wings down against the body, it is still easy to rule in or rule out the presence of a shelled egg or effusion as the main cause of the dyspnea.

Interpreting Avian Radiographs

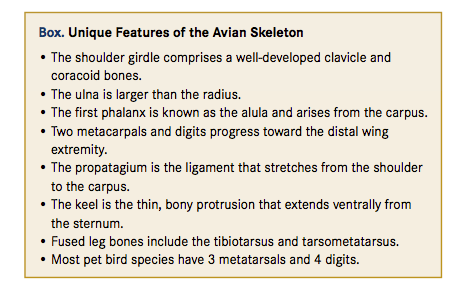

According to Dr. Thompson, it is often easiest to evaluate the skeletal system first on a radiograph and then progress to evaluate the head, neck, and coelom. He highlighted some unique features of the avian skeleton (Box) that veterinarians should be aware of when evaluating radiographs of pet birds.

Evaluating the coelomic contents can also be challenging for veterinarians who are accustomed to dealing with patients that have a diaphragm, Dr. Thompson said. The trachea is often more prominent than in cats and dogs, and there is wide variation in its prominence depending on the species-related variation in syringeal anatomy. Bird lungs do not expand, he noted, but are visible adjacent to the thoracic spine on both the ventrodorsal and lateral views. However, the air sacs are visible around the viscera, and the clavicular air sac is located just below the shoulder joint overlying the muscles. The heart is easily seen on both ventrodorsal and lateral views, Dr. Thompson said, as are 2 prominent main arteries, although the lateral projection provides the best visualization of the vessels.

The crop is seen at the thoracic inlet and varies in size depending on the amount of food or fluid it contains. The proventriculus is seen overlying the liver on both radiographic views, but the liver itself is best visualized on the lateral projection, he stressed. The ventriculus is also visible on both lateral and ventrodorsal views.

Dr. Thompson also noted that improvements in digital radiography now routinely allow visualization of the spleen on the lateral radiographic view. They also allow routine evaluation of the kidneys adjacent to the lumbar vertebrae and synsacrum, as well as ovaries and testes. In hens, reproductive structures can also be examined, he added, including ovarian follicles and calcified eggs in the shell gland. He noted that the lateral view is best to allow visualization of the cloaca.

Other Imaging Procedures

In conclusion, Dr. Thompson noted that ultrasound is typically of limited use in birds because of the presence of air sacs around the coelomic contents. Therefore, barium is still used routinely in pet birds to assess the gastrointestinal tract, especially the proventriculus and ventriculus, he emphasized.

However, he added that ultrasound does play some role in avian diagnostics. For example, the presence of effusion improves visibility and facilitates use of ultrasound to perform echocardiography to evaluate the heart and its potential involvement in causing the effusion, he said.

Dr. Parry, a board-certified veterinary pathologist, graduated from the University of Liverpool in 1997. After 13 years in academia, she founded Midwest Veterinary Pathology, LLC, where she now works as a private consultant. Dr. Parry writes regularly for veterinary organizations and publications.