Still waters: How traumatic stress is poisoning the veterinary profession

For veterinary professionals, compassion fatigue, burnout and depression often flow from a problem far upstreampsychological trauma. And most of us dont even realize were suffering.

full frame / stock.adobe.com

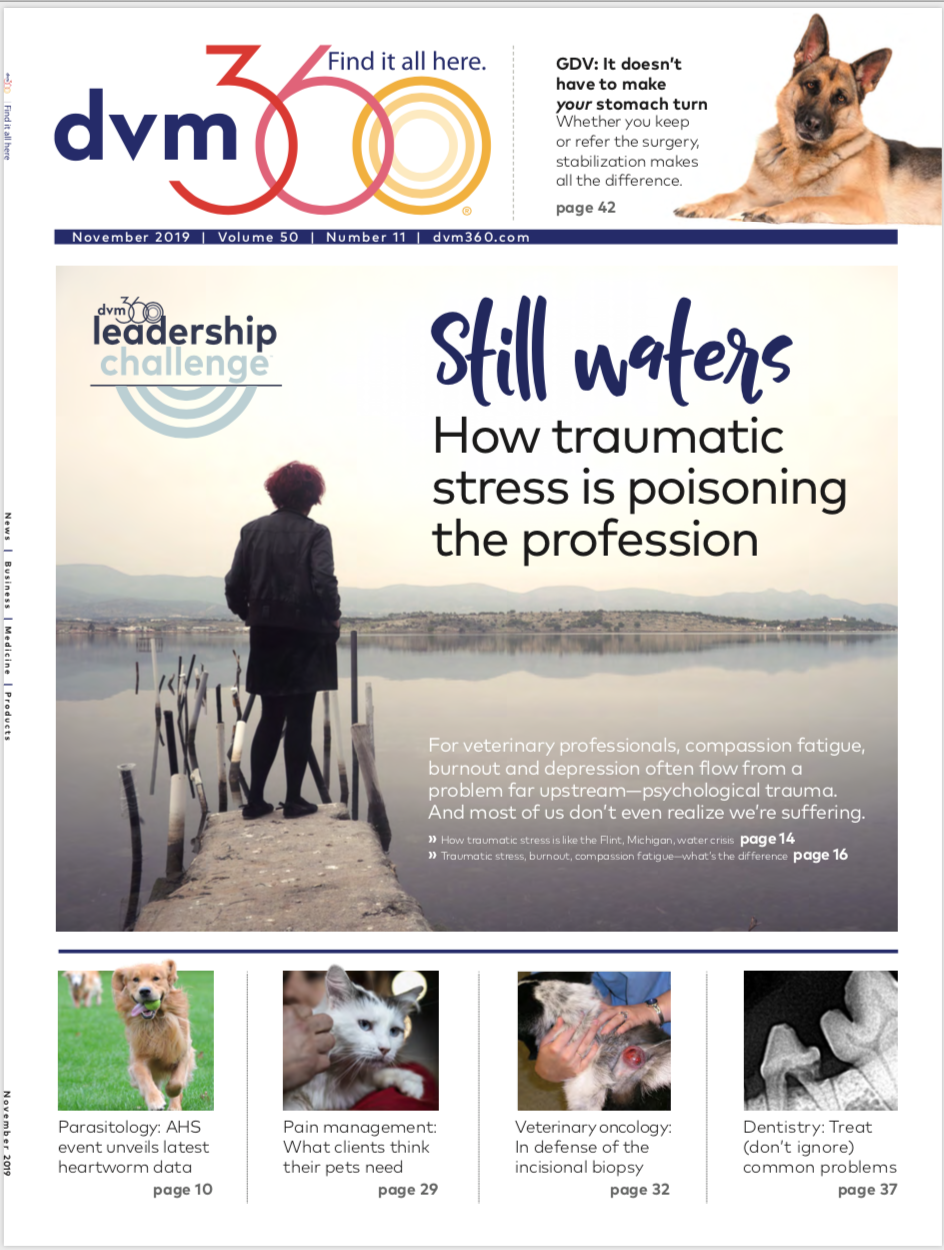

Just like a beautiful river can carry toxins that harm its surroundings, the human brain can hold onto pain in a way that damages health and wellbeing. (full frame / stock.adobe.com)Traumatic stress flows freely through the veterinary profession, but most veterinarians aren't practicing with an active awareness of this fact. And how can we solve a problem without understanding it? Simple answer: We can't.

As a profession, we've focused primarily on symptoms-compassion fatigue, burnout, even suicide-but these are actually linked to the end stage of unresolved traumatic stress. Traumatic stress precedes all of these conditions we name so commonly in veterinary medicine. Educating ourselves on the effects of trauma will improve our health, the health of our practices and the strength of our teams.

What you don't know can hurt you

It's fascinating to me as a medical professional who's undertaken years and years of schooling that there's still a vast amount I don't know about healing and medicine. I was faced with this reality when I stumbled into the field of psychological trauma. It was the first time I became starkly aware that what I didn't know could hurt me-and had likely been hurting me for years.

Within the first few years of my graduating vet school, I began to question my career choice. I found myself struggling to understand why I felt so terrible when I left work, especially after dealing with emotionally intense clients and situations involving patients. In my search for answers, I came across the book The Body Keeps The Score by Bessel Van Der Kolk. Through it I realized I was experiencing traumatic stress and, in turn, not recovering effectively from it.

Psychological trauma, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), occurs when an individual experiences an event involving death or serious injury and feels “intense fear, helplessness or horror” as a result. Once I realized this was happening in my work as a veterinarian, I sought help through therapy. Unfortunately, I couldn't find a single trauma-informed therapist where I lived at the time in Hawaii.

Eventually I realized I didn't have time to wait around for help-I needed to help myself. I contacted the International Association of Trauma Professionals and asked if I could pursue training as a veterinarian. They allowed me to enroll in an online course, which led to my certification as a clinical trauma professional.

Around this time I was also diagnosed with an illness that I would later discover was a tumor. While benign, it was causing health complications and affecting my quality of life. It took me almost three years of restorative therapy and multiple surgeries to finally resolve my health issues. I believe it was my discoveries related to traumatic stress that ultimately led to my healing and also helped me stay in a career I love. This is why I am passionately trying to spread the word about this epidemic that is quietly destroying us.

A poisoned river

As an analogy, we can compare psychological trauma to the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. On April 25, 2014, officials in Flint switched the city's water supply to the Flint River in an effort to cut costs. This change introduced water contaminated with lead and other toxins into homes and businesses. The city of Flint was ill-equipped to handle its financial crisis, so officials made a decision that appeared to be sound initially. But they didn't have enough support or resources to make sure their decision was safe, and eventually this led to an even greater crisis-one that threatened the health of the city.

In this scenario you can think of your brain as the city officials-the ones in charge-and your body as the city. The brain likes to be efficient and economical. It commands decisions that affect the rest of the body. After a traumatic experience, if the trauma is not successfully resolved, the brain often employs a “diversion” tactic. This helps the brain save on costs associated with dealing with the pain of the trauma. However, this can lead to more serious consequences downstream.

Our brains are often not equipped to process trauma effectively. Some people have better resources (such as a personal support system), and some have what is known as inherent resiliency (systems in place to quickly mitigate adverse situations). Likewise, some cities have better financial health and community support while others do not. Luckily for your brain (and the city of Flint), help can come from elsewhere, and you can heal even after trauma. However, if you continue to be unaware that the well is poisoned, or ignore signals of distress, you could be harmed irrevocably.

A coverup of the brain

It's interesting how, when the water change initially occurred in Flint, some residents tried to alert officials but were silenced. This coverup led to even more sickness in Flint, even after the truth came out. If the facts had been revealed sooner, fewer people would have had to suffer, and the damage may not have been as catastrophic.

Similarly, the brain likes to protect itself if it feels like it's under attack, so it hides facts and keeps secrets, hoping things will move along undisturbed. Often with trauma, the body feels or senses something is wrong and tries to alert the brain. But the brain shuts off or ignores these alerts because it's too busy worrying about other things coming its way, and it has a difficult time distinguishing what to prioritize. In the end, the poison continues to flow downstream, causing residual effects for years to come. This is how secrets can continue to poison the well.

Lovely on the surface

A person who's passing by the Flint River and doesn't know its history might see it as beautiful and refreshing. They might want to take a dip in the river or fish from it. But in the depths is poison. It can also poison things around it: soil, foliage and so on. Often you can't tell just by looking at something if dangers are hidden beneath the surface. Some things are hidden so well that even the person who did the original hiding has forgotten where and what it is.

Just as with lead poisoning, the effects of unresolved traumatic stress build up over months or years before outward manifestations of the toxicity appear. Symptoms can include developmental delays, learning difficulties, irritability, loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, abdominal pain, high blood pressure, joint and muscle pain, headaches and mood disorders. These are symptoms of lead poisoning-but they can also be symptoms of unresolved traumatic stress.

What you do know can heal you

What is the cure for lead poisoning? Treatment involves avoiding further exposure to lead, chelation therapy (if blood levels are confirmed around 45 micrograms/dl) and dietary changes (such as making sure your iron and calcium levels are adequate, as this prevents lead from being able to bind, be absorbed or be stored). There you have it: (1) Reduce exposure. (2) Therapy. (3) Protectants.

What is the cure for psychological trauma? The exact same steps.

Reducing exposure. Unfortunately in the veterinary field, we are repeatedly exposed to traumatic situations and are at risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; sometimes referred to as “primary traumatic stress disorder”) and secondary traumatic stress disorder (STSD). Therefore it can be a struggle to reduce our exposure to sources of traumatic stress, especially if we don't even realize we're suffering. Just like the people of Flint, we can't resolve our crisis until we know our level of exposure. This dvm360 Leadership Challenge includes many examples of how traumatic stress can manifest in veterinary medicine; find more on my author page at dvm360.com/hilaldogan.

Treatment and protection. The most healing treatments for trauma involve knowledge and support. Understanding causation and knowing what to do empower us to get back in the driver's seat after our brains have been on autopilot. Having people around us who can support us-whether it's in our workplace culture or with the help of a professional therapist-will help us find our blind spots.

I hope you will continue to explore this topic through a deep dive into this dvm360 Leadership Challenge. If you find yourself thinking, “Nope, this is of zero interest to me,” I still urge you to keep reading, as it might help someone you know or work with. For now I will leave you with a quote from one of the fathers of research in the area of psychological trauma:

“If you are experiencing strange symptoms that no one seems to be able to explain, they could be arising from a traumatic reaction to a past event that you may not even remember. You are not alone. You are not crazy. There is a rational explanation for what is happening to you. You have not been irreversibly damaged, and it is possible to diminish or even eliminate your symptoms.” -Peter A. Levine, Waking the Tiger, Healing Trauma

Dr. Hilal Dogan is a certified clinical trauma professional and frequent Fetch dvm360 speaker who is a veterinary relief practitioner in Denver, Colorado. She started the Veterinary Confessionals Project (dvm360.com/vetconfessions) as a senior veterinary student at Massey University in New Zealand.