What is and is not trauma and compassion fatigue

Heres an overview of what psychology experts say constitutes trauma, plus some examples that place these definitions firmly in the world of veterinary professionals.

Orawan/stock.adobe.com

Every year, Bessel Van Der Kolk, MD, founder and medical director of the Trauma Center in Brookline, Massachusetts, holds an international trauma conference in Boston. As with veterinary conferences, leading research is presented, problems are discussed and solutions are explored. I attended the event this year with the goal of asking some of the experts if they thought veterinary professionals were exposed to significant traumatic stress. The short answer from Dr. Van Der Kolk? Yes. The long answer is a bit more complex, but it starts with definitions.

“One does not have to be a combat soldier, or visit a refugee camp in Syria or the Congo to encounter trauma. Trauma happens to us, our friends, our families and our neighbors. Trauma by definition is unbearable and intolerable.” -Bessel Van Der Kolk, The Body Keeps The Score

These definitions are not provided for self-diagnosing, or diagnosing others, but they will provide you with a better understanding of traumatic stress. This information can provide a starting point for a conversation with a mental healthcare professional if you recognize any of these symptoms in yourself or others. These are paraphrased, and if you would like to see full definitions outlined exactly, please refer to the most current version of the DSM.

Primary stress injuries

Primary stress injuries are brain and body changes that happen directly to you. Secondary stress injuries, which I'll cover later, happen to someone else, but they create brain and body changes in you.

Acute stress is the most cost common form of stress. In the short term, it doesn't have enough time to do the extensive damage associated with long-term stress. The most common symptoms are:

- Emotional distress, a combination of the three stress emotions-anger or irritability, anxiety, and depression.

- Muscular problems, including tension headache, back pain, jaw pain and tensions that lead to pulled muscles and tendon and ligament problems.

- Stomach, gut and bowel problems, such as heartburn, acidic stomach, flatulence, diarrhea, constipation and irritable bowel syndrome.

Acute stress can lead to transient overarousal, which manifests physically as elevation in blood pressure, rapid heartbeat, sweaty palms, heart palpitations, dizziness, migraine headaches, cold hands or feet, shortness of breath, and chest pain.

Acute stress can crop up in anyone's life, and it's highly treatable and manageable.

Acute stress disorder (ASD) is the initial reaction to witnessing or experiencing psychological trauma. The DSM characterizes ASD with these principal criteria:

- Experiencing intense fear, helplessness or horror in response to a traumatic experience.

- Displaying three or more of the following dissociative symptoms:

- Emotional numbing

- Detachment or absence of emotional responsiveness

- Reduced awareness of surroundings

- Derealization (a feeling that the external world is unreal) or depersonalization (a feeling of being detached from oneself or one's surroundings)

- Dissociative amnesia (blocking out memory of personal information).

- Exhibiting at least one symptom from each of the following groups:

- Re-experiencing the event (recurring thoughts, memories, dreams or flashbacks)

- Avoidance of trauma-related stimuli (deliberately avoiding reminders of the trauma)

- Anxiety or increased arousal (increased autonomic nervous system activity)

- Significant distress or functional impairment that persists.

- Lasts more than two days but less than four weeks

- If the duration of ASD exceeds four weeks, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be diagnosed.

Psychological trauma has two prerequisites-so-called A1 and A2:

A1. A direct personal experience of an event that involves actual or threatened death or serious injury, or other threat to one's physical integrity; or witnessing an event that involves death, injury or a threat to the physical integrity of another person; or learning about an unexpected or violent death, serious harm or threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or other close associate.

A2. An experience of “intense fear, helplessness or horror” following the event.

Primary traumatic stress happens directly to you. If you can't cope, you may develop PTSD.

Examples in the world include traumatic accidents, death, rape or sexual assault, war, violence and even neglect.

More specific examples in veterinary medicine might include being attacked or bitten by animals, threatened by clients or other people, anesthetic deaths or other procedure-related deaths, as well as professional mistakes such as surgical errors or drug overdoses.

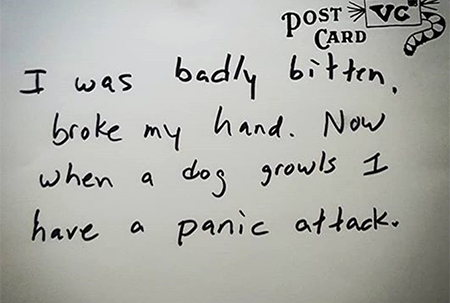

Consider this example from the Veterinary Confessionals Project:

I was badly bitten and broke my hand so when a dog growls, I have a panic attack.

This could be an example of PTSD (if it last more than four weeks), because the response to a dog growling is “exaggerated.” Having a self-described panic attack every time a dog growls would severely impede your ability to effectively deal with the situation. A more appropriate response would be to back off and consider sedation or a muzzle.

Secondary stress injuries

Remember, secondary stress injuries happen when you observe something happening to another but feel effects in your own brain and body. The difference between primary and secondary stress injuries are in relation to how they occur, but the end result is the same.

To understand secondary stress better, we need to understand mirror neurons, a strange category of neurons that function through observation. For instance, if I see you smile, my own neurons fire like they would if I were smiling-this would be observable on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This works the same with pain: If I see you get hurt, my brain lights up like I got hurt. The way mirror neurons function and their role is still a topic of controversy (I talk about them here regarding anesthesia cases), but experts believe they're linked to empathy, because they “light up” on brain imaging studies and affect how we respond when we see or hear something.

How does this translate to veterinary medicine? Well, there are both positive and negative impacts. When we see a happy, cute, bouncy puppy, we also get happy, cute and bouncy. Even if we don't outwardly display this, we feel it. However, when we see a sick, emaciated, dying animal that appears to be in pain, we also take on that pain. We may seek to give it pain medication right away or euthanize it in an effort to stop the pain. We end up taking on secondary trauma not only from animals, but also from our clients and coworkers.

So, secondary traumatic stress occurs when you observe something traumatic happening to someone else. If you can't cope, you may develop secondary traumatic stress disorder (STSD, aka compassion fatigue).

Recently I saw this comment on Instagram from a veterinary colleague: “Doctor was being mauled in the [exam] room and I was at the far end of the hospital on the microscope. I still get the shakes if there is a loud noise and I am at the scope.”

In this example, the person is “triggered” to relive somebody else's traumatic event by any loud noise they hear when they're at the microscope. If symptoms like "the shakes" have lasted more than four weeks, a mental health professional may diagnose this individual with STSD. You can see how crucial it is to understand how trauma affects our team: This person may avoid performing tasks at the microscope, and that could negatively affect their ability to work.

Controversies surrounding trauma definitions

Clinicians and researchers have criticized some aspects of the definition of psychological trauma. The debate over what constitutes a traumatic event emerged with the first inclusion of the diagnosis in the third edition of the DSM and has persisted. Some postulated that weakening the A1 criteria (direct experience of a trauma) had detrimental outcomes in client care and supported a too-narrow definition that didn't include those with secondary traumatic stress. They argued that the fourth edition DSM's broad definition of trauma led to overdiagnosis of PTSD resulting from less-threatening events. Others starkly disagreed, suggesting that what may be traumatic for one individual may not be for another, and that an attempt to include all possible traumatic events within the context of a diagnosis was futile.

Unfortunately, experts don't currently agree on what definitively counts as a traumatic event or situation-the individual perceives it as traumatic or nontraumatic. In other words, trauma is in the eye of the beholder. For instance, when I'm working in the ER, I may not be traumatized when I see a brachycephalic dog whose eyeball popped out after the dog was stepped on. As a matter of fact, I see it as an exciting challenge because I love trying to replace that eyeball. It can be gratifying. However, to the pet owner, or even someone else working in the hospital, that same event may be perceived as traumatic. With the last case of this I saw, I sent a picture to my sister and a friend before and after tarsorrhaphy. They were disturbed and requested no more photos of that ever again.

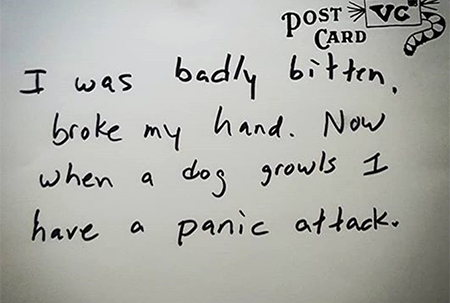

Compare our example from earlier to another post from the Veterinary Confessionals Project:

I was badly bitten and broke my hand so when a dog growls, I have a panic attack.

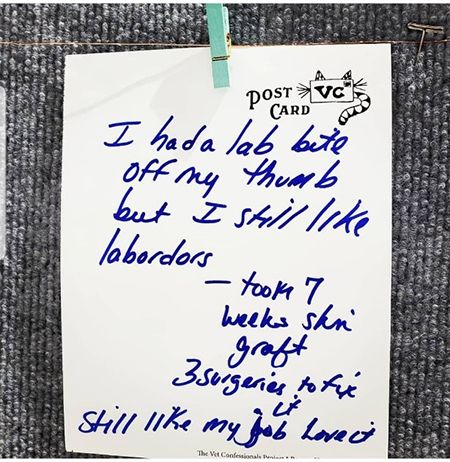

I had a Lab bite off my thumb but I still like Labradors. Took 7 weeks of skin grafts and 3 surgeries to fix it. Still like my job. Love it.

These are two similar events that could have been equally traumatic. Yet it seems the first person was traumatized, and the second person wasn't.

And animal trauma?

The brachycephalic dog with proptosis may be traumatized or it may not be. We know that psychological trauma likely exists in mammals with similar brain structure to ours. We all have seen some animals that are extremely resilient and can bounce back from anything and others that seem traumatized by the smallest event. Yet our knowledge in this area is still infantile. Perhaps once we learn more about psychological trauma in humans, we can dive deeper into exploring what it might be like for the animals we treat. In turn, perhaps similar healing methods used to heal psychological trauma in people could be used someday to help heal psychological trauma in animals.

Frequent Fetch dvm360 speaker Dr. Hilal Dogan practices medicine in Denver, Colorado. She started the Veterinary Confessionals Project as a senior veterinary student at Massey University in New Zealand.