Unique Aspects of Feline Lymphoma

Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of this common cancer are more successful with an understanding of the many differences in the disease between dogs and cats.

Lymphoma is different in cats than in dogs, emphasized Jennifer Pierro, MS, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology), an oncologist at Veterinary Cancer Group in Los Angeles, California. Presenting at the 2017 Purdue Veterinary Conference in West Lafayette, Indiana, Dr. Pierro discussed updates in feline lymphoma and shared some unique aspects of how the disease differs in cats compared with dogs.

In dogs, the typical presentation of lymphoma is high-grade multicentric nodal disease. However, cats more commonly develop gastrointestinal (GI) lymphoma, typically without generalized lymphadenopathy. Clinical signs of lymphoma in cats also tend to be nonspecific, mimicking those of a range of other conditions such as pancreatitis and renal failure.

PROGNOSIS

“The prognostic factors in cats are very frustrating and not quite as cut-and-dried as in dogs,” Dr. Pierro said. In dogs, lymphoma immunophenotype (B cell vs T cell) is the most important prognostic factor: “B is better, and T is tougher,” she said. However, in cats, different lymphoma immunophenotypes tend to be “associated with different disease locations but don’t affect the outcome.”

According to Dr. Pierro, histologic subtype is an important prognostic factor in cats, with small cell (also known as low-grade) lymphoma carrying a better prognosis than that of large cell (high-grade) lymphoma. Small cell lymphoma is composed of proliferations of mature lymphocytes, and the disease usually has an indolent course. It most commonly arises in the GI tract but can also occur in other locations, Dr. Pierro said.

Disease location is another prognostic indicator, she added. For example, cats with nasal lymphoma can survive for years, whereas those with renal lymphoma tend to survive only months.

Response to treatment is a third prognostic indicator. Cats with lymphoma do not respond as well to chemotherapy as dogs do, Dr. Pierro said. “Between 50% and 75% of cats will go into remission, but those that go into complete remission can do better than dogs,” she emphasized.

RELATED:

- Human Resistance to Feline Leukemia Virus Infection

- Primary Mediastinal Lymphoma in Dogs

She also noted that cats with feline leukemia virus that develop lymphoma are more difficult to treat—and they are about 40 times more likely to develop lymphoma in the first place.

SMALL CELL GASTROINTESTINAL LYMPHOMA

Dr. Pierro noted that affected cats with small cell GI lymphoma typically present with a variety of nonspecific clinical signs, including weight loss, appetite changes, vomiting, and diarrhea. Ultrasonographic findings in these cases commonly include thickening of the intestinal muscularis layer, altered wall layering, and lymphadenopathy, she said.1

Dr. Pierro reminded veterinarians that a diagnosis of small cell lymphoma cannot be made on the basis of fine-needle aspiration cytology of lymph nodes alone. However, she recommended still collecting an aspirate from enlarged lymph nodes to rule out other diagnoses such as large cell lymphoma and mast cell tumor.

Definitive diagnosis of small cell GI lymphoma requires biopsy, she said, especially to differentiate it from inflammatory bowel disease. Biopsy samples can be obtained surgically or endoscopically. Endoscopy is less invasive and requires a shorter hospitalization time. Although endoscopy allows visualization of the intestinal mucosa,2 Dr. Pierro noted that it does not allow access to every region of the GI tract. Because lymphoma may arise only in the ileum in some cats, using endoscopy to obtain biopsies requires both upper endoscopic and colonoscopic approaches.3 Additionally, endoscopy does not allow for collection of full-thickness biopsy samples, she said.

In addition to enabling collection of full-thickness samples from multiple parts of the small intestine, surgical biopsy allows veterinarians to obtain samples of lymph node and liver, she added. And although the surgical approach is more invasive than endoscopy, Dr. Pierro noted that cats with lymphoma do not seem to be at high risk for postoperative dehiscence after full-thickness GI surgery.4

CHEMOTHERAPY PROTOCOLS FOR LYMPHOMA

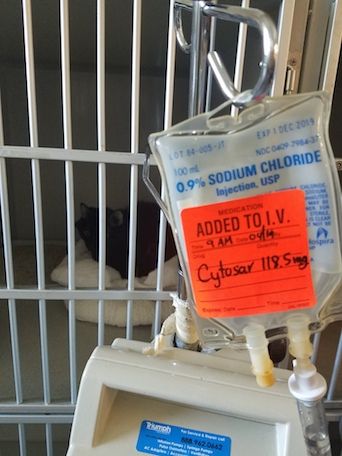

Although most dogs will achieve clinical remission with standard-of-care CHOP chemotherapy (vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) for a median survival time of 1 year, she noted that cats with large cell lymphoma that receive CHOP respond to treatment 50% to 75% of the time, with a median survival time of 6 to 9 months.

However, cats with lymphoma that do go into remission with CHOP frequently outlive dogs that go into remission, she emphasized. Data from a 2005 study showed that overall median survival time of cats treated with CHOP was 7 months, but the median survival time for those achieving complete remission was almost 2 years.5

The CHOP protocol is also generally well tolerated in cats, said Dr. Pierro. In dogs, doxorubicin is the most effective drug in the CHOP protocol and is sometimes used as single-agent therapy. However, single-agent doxorubicin does not seem to be as effective for high-grade feline lymphoma as it is for dogs with lymphoma.6

However, a COP-based protocol (vincristine, cyclo- phosphamide, prednisone) has been shown to be effective in many cases of feline lymphoma. And, as with CHOP protocols, cats that go into clinical remission with COP chemotherapy can have extended survival times, Dr. Pierro said.

Treatment of cats with small cell lymphoma includes prednisone and the oral chemotherapy agent chlorambucil. This protocol has minimal adverse effects, and most cats respond well, with a median survival of 1 to 3 years, Dr. Pierro said.7 “I find that most of these cats do not die because of their lymphoma,” she added.

Chemotherapy-Associated Toxicities

In cats receiving CHOP chemotherapy, “anorexia is by far the most common toxicity that we see,” said Dr. Pierro. Dogs receiving CHOP have unique toxicities associated with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin, she noted. Cyclophosphamide can cause sterile hemorrhagic cystitis in dogs as a result of an inactive metabolite of the drug, but this does not occur in cats, Dr. Pierro said. And although doxorubicin can cause cumulative cardiac toxicity in dogs, it does not cause clinical cardiac toxicity in cats, she added. However, it can cause cardiac muscle damage in cats, which may be seen histologically after postmortem examination. Nevertheless, Dr. Pierro stressed that doxorubicin therapy is associated with renal toxicity in cats and advised veterinarians to monitor urine specific gravity in their feline patients that receive this drug.

Lomustine tends to be associated with an unpredictable neutropenia in cats, she noted, compared with a more predictable neutropenia in dogs. However, this drug causes minimal hepatotoxicity in cats, unlike in dogs.

Myelosuppression most commonly arises in cats receiving prednisone and chlorambucil, Dr. Pierro said, although rare cases of idiosyncratic liver toxicity have been reported, as well as 1 case of central nervous system toxicity.

Other Unique Lymphoproliferative Diseases

In concluding, Dr. Pierro also discussed 2 other lymphoproliferative diseases that may arise in cats.

Hodgkin-like Lymphoma

Hodgkin-like lymphoma is similar clinically and histologically to Hodgkin lymphoma in humans. It is a localized disease that involves lymph nodes of the head and neck and typically carries a relatively favorable prognosis. Histologically, Hodgkin-like lymphoma predominantly comprises proliferations of small lymphocytes, along with the presence of characteristic large Reed-Sternberg—like cells. Dr. Pierro emphasized that this form of lymphoma is considered slowly progressive and treatment usually involves a combination of surgery, radiation, and, potentially, chemotherapy.

Cutaneous Lymphocytosis

Cutaneous lymphocytosis (also known as pseudolymphoma) presents as seborrheic and plaque-like lesions of the skin.8 In some cases, this condition can look like allergic skin disease, Dr. Pierro said. Histologically, cutaneous lymphocytosis comprises proliferations of heterogeneous but well-differentiated lymphocytes. Because the diagnosis is not always cut-and-dried, however, she advised veterinarians to submit biopsy specimens to a dermatopathologist for evaluation. This disease progresses slowly, but “we don’t really know how to treat it,” she noted. As a consequence, no established treatment protocols exist to help veterinarians manage these cases. However, according to Dr. Pierro, treatment often involves using prednisone and oral chemotherapy agents. Although chemotherapy may not always be very effective, it may help slow progression of the disease, she added. In general, this disease has a waxing and waning nature, but it does not seem to cause many problems long term, Dr. Pierro said, and most cats with cutaneous lymphocytosis can live a long time.

References:

- Daniaux LA, Laurenson MP, Marks SL, et al. Ultrasonographic thickening of the muscularis propria in feline small intestinal small cell T-cell lymphoma and inflammatory bowel disease. J Feline Med Surg. 2014;16(2):89-98. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13498596.

- Willard MD, Lovering SL, Cohen ND, Weeks BR. Quality of tissue specimens obtained endoscopically from the duodenum of dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219(4):474-479.

- Scott KD, Zoran DL, Mansell J, Norby B, Willard MD. Utility of endoscopic biopsies of the duodenum and ileum for diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease and small cell lymphoma in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25(6):1253-1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00831.x.

- Smith AL, Wilson AP, Hardie RJ, Krick EL, Schmiedt CW. Perioperative complications after full-thickness gastrointestinal surgery in cats with alimentary lymphoma. Vet Surg. 2011;40(7):849-852. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2011.00863.x.

- Milner RJ, Peyton J, Cooke K, et al. Response rates and survival times for cats with lymphoma treated with the University of Wisconsin-Madison chemotherapy protocol: 38 cases (1996-2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227(7):1118-1122.

- Kristal O, Lana SE, Ogilvie GK, Rand WM, Cotter SM, Moore AS. Single agent chemotherapy with doxorubicin for feline lymphoma: a retrospective study of 19 cases (1994-1997). J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15(2):125-130.

- Fondacaro JV, Richter KP, Carpenter JL, Hart JR, Hill SL, Fettman MJ. Feline gastrointestinal lymphoma: 67 cases (1988-1996). Eur J Comp Gastroenterol. 1999;4(2):5-11.

- Gilbert S, Affolter VK, Gross TL, Moore PF, Ihrke PJ. Clinical, morphological and immunohistochemical characterization of cutaneous lymphocytosis in 23 cats. Vet Dermatol. 2004;15(1):3-12.