Use of photodynamic therapy to treat equine periocular squamous cell carcinoma

Emerging modality shows promise in this difficult-to-treat veterinary ophthalmic condition.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common neoplasm of the equine eye and ocular adnexa and the second-most-common tumor in horses overall.1-5 Horses older than 10 years of age seem to be most predisposed, with Belgians, Clydesdales and other draft horses experiencing the highest prevalence, followed by Appaloosas and paints. Arabians, thoroughbreds and quarter horses have the lowest prevalence of SCC. Horses with less skin-coat pigment-white, grey and palomino hair coats-also have a greater prevalence of periocular SCC (PSCC). Lower prevalence occurs in horses with bay, brown or black hair coats.

Early squamous cell carcinoma of the lower eyelid. All photos courtesy of Dr. Caryn Plummer, University of Florida.

Clinical signs vary according to the location and type of SCC. Carcinoma of the conjunctiva or limbus may be asymptomatic, with the only visible sign of the tumor a small white to light pink mass.1 Limbal and corneal SCCs have a “cauliflower” appearance. Most often the lesions are light pink and begin at the lateral limbus, extend into the cornea, and occasionally reach into the conjunctiva. Early lesions are flat and rough. Corneal lesions can sometimes mimic a scar, eosinophilic keratitis or granulation tissue. PSCC of the third eyelid can be proliferative or erosive, beginning at the eyelid margin. Eyelid masses tend to be more varied in appearance, are often ulcerative, and usually occur on lightly pigmented eyelids but also may occur on darker eyelids.

Corneal squamous cell carcinoma.

“Upper eyelid SCC is more problematic than lower eyelid SCC in many cases because the upper eyelid is more mobile and provides greater protection of the globe,” says Caryn Plummer, DVM, DACVO, associate professor of comparative ophthalmology and service chief of ophthalmology at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine. “Resections that result in limited mobility can significantly impact the function of the eyelid and result in exposure issues for the eye.”

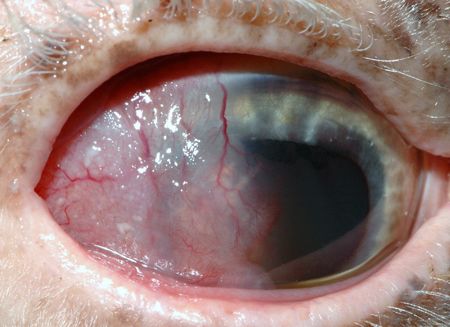

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lateral canthus eyelid.PSCC may be invasive and result in blindness. In 10 to 15 percent of horses it metastasizes to other organs, notably the local lymph nodes, nose, salivary glands and lungs. PSCC may require removal of the visual globe with significant obvious adverse effects on a horse's performance and function.

Advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the medial canthus eyelid.

PSCC has been correlated with exposure to UV sun radiation, a low degree of periocular pigmentation and genetic factors that have not yet been determined. Light-colored horses exposed to high levels of sun-those at higher altitudes or other areas with more intense sunlight-are especially at risk for PSCC.

Third eyelid squamous cell carcinoma.

“PSCC is very frustrating because it is locally aggressive and destructive,” Plummer says. “It does not metastasize very commonly, though it sometimes travels to the nasal passages, to the lungs and to the brain. PSSC can invade deep structures of the eye and orbit, leading to loss of function and to significant impact on the animal's quality of life and lifespan.”

Diane Hendrix, DVM, DACVO, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine, says PSCC is usually diagnosed on the basis of biopsy results, although its appearance is quite characteristic. Some horses may have SCC elsewhere on the body at the time of ocular SCC diagnosis.

“When the lesions are ulcerated, mucopurulent or serous discharge is often present,” Hendrix says. “It's not unusual to have more than one part of the eye affected with SCC. Local invasion can extend into the orbit, guttural pouch or nasal cavity, causing bony destruction. Third eyelid tumors and eyelid SCC tend to spread and metastasize more frequently than limbal SCC.”

PSCC must be differentiated from other tumors such as papilloma and sarcoid, from parasitic disease and from inflammatory lesions such as abscesses, granulation tissue and foreign-body reactions.

Treatment

Diagnosing SCC early is important, when the tumor is relatively small or limited, so therapy can be effective. The main differential for SCC is granulation tissue. “If a veterinarian tries treatment with a topical steroid, no effect will be seen if the lesion is squamous cell carcinoma,” Hendrix says.

Existing treatments for PSCC are somewhat limited in their effectiveness. Surgical resection is especially problematic, experts say. According to Giuliano and colleagues,2-6 the periocular skin in horses adheres tightly to the underlying fascia and bone, which often precludes successful reconstructive eyelid surgery. If surgical reconstruction is unsuccessful, it's likely that the globe will be lost to the consequence of keratitis and tear film maintenance and distribution.

“Around the equine eye there's not a lot of extra skin that can be harvested for reconstruction, making surgical repair difficult,” Plummer says. “So it's very important when doing an excision for SCC, especially with a large neoplastic lesion, that function of the remaining tissues be taken into consideration and that enough functional tissue is left to provide adequate protection for the globe. However, this can make achieving clean margins difficult or impossible.”

In addition to surgical excision, several other therapies are used for more advanced SCC, including cryotherapy, topical and intratumoral chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Efficacy varies among patients.

Surgery. Surgery can be successful in some cases, especially when the lesion is on the third eyelid. “Removing all of the third eyelid will remove all the tumor,” Hendrix says. “Or, if corneal or eyelid SCC is so extensive that blindness has occurred, enucleation may be curative. Additionally, carcinoma in situ in the conjunctiva may be surgically excised.”

However, in other locations surgery can leave damaged or precancerous areas adjacent to the mass. “Leaving neoplastic cells behind that are not grossly obvious is one reason that surgical excision itself is not frequently warranted,” Hendrix explains. “In dogs, one can use extensive blepharoplastic techniques using skin grafts

to create a new eyelid, but horses do not have that redundant skin, so it is not an option.”

Cryotherapy. Cryotherapy is often available to general practitioners. For lesions that affect the eyelid, third eyelid or cornea, the mass is debulked and a double freeze-thaw cycle with liquid nitrogen (using a probe rather than spray) is performed. This treatment can be effective and create a cure.

Radiation. Two forms of radiation therapy can be effective: strontium-90 and iridium beads. With strontium-90 therapy, the mass is debulked and a probe is placed directly onto the affected area. If the remaining tumor is very superficial, strontium-90 therapy can be highly effective. This modality is primarily used for corneal, corneolimbal and conjunctival SCC. It is a referral procedure and not typically available to the general practitioner.

Iridium beads can also be placed into eyelid tumors, which is very effective for treating eyelid SSC. However, their use is offered only at a few university facilities, Hendrix says. The horse has to be placed in isolation and personnel are exposed to the radiation, so the procedure is falling out of favor.

Chemotherapy. Intralesional chemotherapy with carboplatin and cisplatin can be effective on eyelid SCC, Hendrix says. Five-fluorouracil can be injected every two to three weeks but will only palliate the tumor and not cure it. Piroxicam may be useful against corneal SCC based on increased COX-1 and COX-2 levels, but no research has been published evaluating its use.

Even with these available treatments, if PSCC is not treated early while the tumors are small, they become larger and much more difficult to treat, with a poorer prognosis.

New treatment: Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy is currently under study as a potential replacement for these therapies or as an adjunct to provide better resolution of PSCC in horses. Researchers hope that photodynamic therapy will enhance residual cell destruction and prevent tumor recurrence.4

“PSCC is one of those diseases where there are several therapeutic options available, but there is not one ‘gold standard' effective therapy,” Plummer says. “Photodynamic therapy is a big boost to our treatment options.”

According to Giuliano and colleagues,4-6 photodynamic therapy entails the use of light and light-sensitive compounds in an oxygen-rich environment to cause localized tissue necrosis. The technique involves injection of a photosensitizing agent, and when the agent is exposed to light of a certain wavelength, energy is transferred in the form of electrons to SCC cell components to induce their destruction.

Injecting the photosensitizing agent for photodynamic therapy (PDT).“Prior to using photodynamic therapy, one excises as much of the tumor as one can,” Plummer explains. “After surgery, you inject a ‘dye' or photosensitizing agent that is taken up by the tumor cells. Once the agent is injected into the tumor bed, it is activated by a light source, a specific wavelength that activates that particular photodynamic therapy agent. In that it only ‘attacks' the rapidly reproducing tumor cells, there is not a lot of collateral damage to adjacent normal cells, because they won't uptake this particular product-that's the advantage of the technique.”

Applying the light source for photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Photodynamic therapy allows clinicians to affect tissue that they would not be able to otherwise, Plummer continues. It does not require extensive resections to achieve clean margins, which allows for more tissue to be functional after treatment.

Photodynamic therapy is still in its early stages with companion animals, but it's being used in people with squamous cell carcinoma tumors with good success, Plummer says. “In small animals and humans the agent is given intravenously, with the light shined solely on the tumor bed,” she notes. “With horses, since they are a much larger animal, the use of IV administration would be cost-prohibitive. That's why local injection into the wound bed is being studied.”

The University of Florida has only begun offering photodynamic therapy recently, “but our cases have been going beautifully,” Plummer continues. “Dr. Giuliano at the University of Missouri has been using photodynamic therapy for a couple of years and had some really nice successes. She hasn't had recurrence of periocular squamous cell carcinoma, as is commonly seen with other modalities. We're not pinning all our hopes on it, but we're cautiously optimistic.”

At this point in time, photodynamic therapy is a referral procedure, currently applicable for eyelid SCC only, but its early success has been encouraging. It may soon become a widespread and valuable new tool available for equine practitioners to effectively treat periocular squamous cell carcinoma.

References

1. Hendrix DVH. Equine ocular squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Tech Eq Pract 2005;4:87.

2. Giuliano EA, MacDonald I, McCaw DL, Dougherty TJ et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of periocular squamous cell carcinoma in horses: a pilot study. Vet Ophthalmol 2008;11 (Suppl 1):27.

3. Giuliano EA, Johnson PJ, Delgado C, Pearce JW. Local photodynamic therapy delays recurrence of equine periocular squamous cell carcinoma compared to cryotherapy. Vet Ophthalmol 2014;17 (Suppl 1):37.

4. Barnes LA, Giuliano EA, Ota J, Cohn LA, Moore CP. The effect of photodynamic therapy on squamous cell carcinoma in murine model: Evaluation of time between intralesional injection to laser irradiation. Vet J 2009;180:60.

5. Ota J, Giuliano EA, Cohn LA, Lewis MR, Moore CP. Local photodynamic therapy for equine squamous cell carcinoma: Evaluation of a novel treatment method in a murine model. Vet J 2008;176:170.

6. Barnes LA, Giuliano EA, Ota J. Cellular localization of Visudyne as a function of time after local injection in an in vivo model of squamous cell carcinoma: an investigation of tumor cell death. Vet Ophthalmol 2010;13(3):158

Ed Kane, PhD, is a researcher and consultant in animal nutrition. He is an author and editor on nutrition, physiology and veterinary medicine with a background in horses, pets and livestock. Kane is based in Seattle.