Anterior stromal puncture: Recommended procedure for treating SCCEDs in dogs

Find out how to perform this technique to treat hard-to-heal corenal ulcers.

Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs) are one of the common ocular ulcers practitioners see in middle-aged dogs of all breeds. A unique characteristic of SCCEDs is an underlying problem with reformation of normal adhesion complexes between the corneal epithelium and underlying stroma.1 Making either small punctures or linear scratches in the superficial stroma likely creates channels for epithelial cells to penetrate the abnormal superficial stromal hyalinized zone noted on histologic examination of these samples.1 Anterior stromal puncture increases extracellular proteins (i.e. collagen IV, laminin, and fibronectin) that are important in epithelial adhesion and are often absent in SCCED lesions.2

In our experience, anterior stromal puncture subjectively results in less scarring and is therefore generally recommended over grid keratotomy; however, the two procedures work through the same mechanism and can be grouped together. These ulcers are often difficult to heal and can take weeks to months and sometimes up to a year to heal if inadequately treated or if left untreated.

Diagnosis

An SCCED should be a differential diagnosis in any middle-aged dog with a history of an uncomplicated nonhealing ulcer that has been present for at least one to two weeks.3 The clinical appearance of loose epithelium around these ulcers aids in diagnosis. This loose epithelium will have a less intense fluorescent color than the erosion when fluorescein stain is applied.

It is important to perform a complete ocular examination and eliminate any underlying cause that would result in delayed corneal healing (e.g. eyelid abnormalities, infection, foreign body, corneal edema, corneal exposure, tear deficiencies).

Treatment

These ulcers are usually not infected and, therefore, only require a topical broad-spectrum antibiotic every eight to 12 hours to prevent secondary bacterial infection. Multiple treatments have been recommended for SCCEDs. We will address epithelial débridement and anterior stromal puncture, also known as punctate keratotomy, multiple punctate keratotomy, and multifocal superficial punctate keratotomy.

Physician ophthalmologists developed this procedure after observing that recurrent erosions did not occur with lacerations or penetrating deep injury, but only with superficial injury.4 A meta-analysis of previous studies showed that débridement with a cotton-tipped applicator averages a healing rate of about 50% and that anterior stromal puncture increases healing rates to 80%.1

View a video of this technique by clicking on the Related Link "Video: Anterior stromal puncture" below.

Step 1. After applying topical anesthetic, use sterile cotton-tipped applicators to remove the redundant epithelium, using radial strokes to facilitate the process. Once a cotton-tipped applicator is moist, it may no longer have enough traction on loose epithelium, so use a new dry sterile cotton-tipped applicator. Continue débridement until all loose epithelial edges are removed. Normal healthy epithelium is tightly adhered to the stroma, so it will not be removed by a cotton-tipped applicator. Often you will end up with a larger erosion than indicated with the initial fluorescein staining.

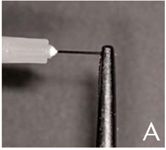

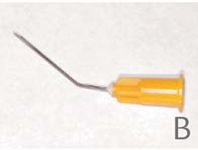

Step 2. After débridement, reapplication of topical anesthetic may be beneficial before continuing. To perform an anterior stromal puncture, clamp a 27-ga needle to a sterile hemostat so that the tip of the needle is barely exposed (Figure A). In the accompanying video, a commercially available anterior stromal puncture needle is being used (Figure B).

Have an experienced assistant stabilize the head and restrain the animal. After parting the eyelids and stabilizing or resting your hand over the patient's orbital rim, begin to make punctures 0.5 to 1 mm apart across the erosion and extending 1 mm beyond into normal cornea. Make sure the needle does not come in contact with the eyelids or third eyelid. If this occurs, discard the needle and begin with a new one to avoid the risk of seeding bacteria into the micropunctures being made.

Since it is often difficult to access defects behind the third eyelid, we recommend using a cotton-tipped applicator to move the third eyelid away or flexing the patient's head downward so that the eye rolls up to facilitate treating this area. Patients should receive topical antibiotics as described above.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kim Sherman, CVT, veterinary ophthalmology technician.

REFERENCES

1. Bentley E, Abrams GA, Covitz D, et al. Morphology and immunohistochemistry of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCED) in dogs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42(10):2262-2269.

2. Hsu JK, Rubinfeld RS, Barry P, et al. Anterior stromal puncture. Immunohistochemical studies in human corneas. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111(8):1057–1063.

3. Bentley E. Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs: a review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2005;41(3):158-165.

4. McLean EN, MacRae SM, Rich LF. Recurrent erosion. Treatment by anterior stromal puncture. Ophthalmology 1986;93(6):784-788.