Bad things good veterinarians say

How to avoid tiny comments that wind up making big trouble for you, your veterinary clients and their pets.

"If you ever want to get rid of that dog, let me know," the veterinarian said with a wink and a smile. I winced.

This was a good veterinarian, really good, yet the words that came out of her mouth were bad, really bad. The owner of the dog exhaled with a gentle laugh and the rest of the appointment was uneventful. So why was I horrified at the joke?

In my 20-plus years of veterinary practice, I've always been a student of communication. I value the words I use with pet parents, staff and colleagues. Maybe that's why this comment struck me as odd. Are there other bad things good veterinarians regularly say?

Oh boy, are there ...

Failing food talks

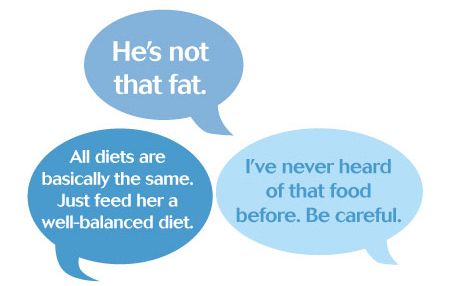

Talking about pet nutrition and excess weight can be tricky. Few subjects are as emotionally loaded as what people feed their pets. We're afraid that we'll expose how little we feel we know. Complicating matters, the "fat gap" widens each year, making clients less aware of weight problems.

Despite these challenges, it's infinitely worse to ignore these topics. Start the discussion by being honest—if a pet is overweight, tell the owner. Avoid the terms fat, chubby and other such adjectives, instead use the Body Condition Scoring system and medical terms such as overweight and obese. Steer the conversation toward the pet's daily activities, such as walking, climbing stairs and getting in and out of cars. Anything that interferes with those activities is a problem. The battle against obesity isn't about a number on a scale—it's about improving health and decreasing disease.

Minimizing medical maladies

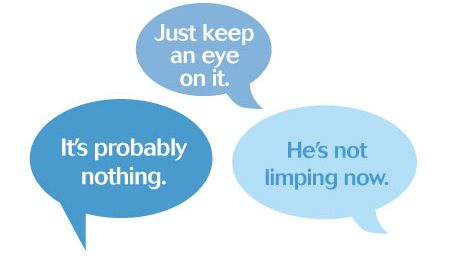

We want to ease our clients' anxiety, especially when we believe there's no need to worry. Nothing's wrong with that, except when we inadvertently minimize a client's complaint. For example, a client brings their dog in with a new lump. You examine the mass and conclude it's most likely a benign fatty tumor. "No need to worry. Just let me know if grows," is good advice—until it isn't. The client monitors the lump and sees no change. A few months later, a similar lump appears. The client remembers that it's "nothing to worry about."

Two months later, the dog comes in with a rapidly growing mass. You're worried it could be a mast cell tumor or sarcoma. You biopsy and diagnose a malignant tumor. Why in the world did this excellent pet parent wait so long? You told her to.

Subtle signs can be significant. Always trust your clients when it comes to describing pain, clinical signs and illness.

Whenever I examine a "sick" pet that fails to exhibit any symptoms during my exam, I tell the client this may be completely normal. Animals are adept at hiding pain and illness. Just because it's not limping, coughing or crying at the moment doesn't mean there's not a problem. Involve owners in deciding how far they'd like to take the diagnostics. Everyone will be happier and you just may save a life.

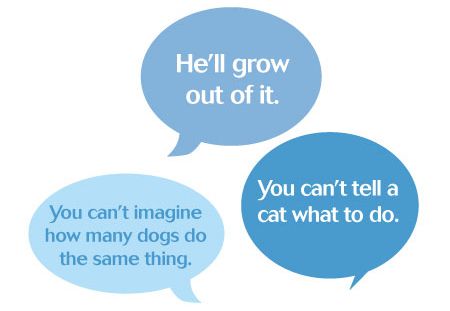

Belittling behavior

Behavior problems could account for roughly one-third of all pets relinquished to U.S. shelters, according to a study published in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. That's a big deal.

The problem with many undesired behaviors is they often escalate. Scratching turns into chewing, which results in a destroyed couch and lands a dog in a shelter. The stakes are simply too high to ignore or diminish even the slightest complaint.

At the end of every routine visit, I ask a simple question: "Is there anything Rover is doing that bugs you, even a little?" That often ignites a few minutes of discussion about seemingly innocent behaviors that could prevent a future behavioral conflagration. No matter how insignificant a habit, action or routine may appear, I'm always thinking future worst-case scenario. It's our duty to help prevent behavioral relinquishment.

Explain to clients that they're right to be concerned about whatever minor flaw they're sharing. Sweeping these conversational crumbs under the rug because you're too busy may have serious, unintended consequences. Sure, you'll occasionally have to cut short a loquacious pet lover. You're not obligated to solve every problem during a single visit. Many cases will require a separate appointment to thoroughly and appropriately address the behavior. Offer a behavioral assessment form for clients to fill out (there's one you can use at dvm360.com/assessmentform).

Finding fault with felines

We all know cats aren't seeing the veterinarian nearly as often as they should. Many cat owners say they don't feel welcome and appreciated. Others rationalize that cats don't need much care. Either way, veterinarians are at least partly to blame for this predicament.

We should be grateful each and every time a pet parent honors us with a cat visit. After all, they don't have to. So if you reframe every client interaction with a heaping dose of gratitude and humility, your practice will begin to glow with caring and compassion.

Remarks such as, "We've missed you" and "It's been a while" are full of derision and judgment. Don't be that practice. Be the clinic that says, "So glad to see you, Ms. Waters! How's Garfield?" Focus on the value of your service, let bygones be bygones and be thankful the client is with you today.

Cats require attention, some cats more than others. They need food, shelter, regular vaccinations, affection and daily litterbox cleaning. In my opinion, they're the highest-maintenance "low-maintenance" pet you can share your home with. Be careful tossing around comments that indicate otherwise. Tell clients a cat is like a dog that doesn't need to be walked outside but does require its ego stroked daily. I love cats, but I'm not trying to fool anyone that they're easy pets. We can increase feline visits by disproving the myth that cats require little care. It begins with the words we choose.

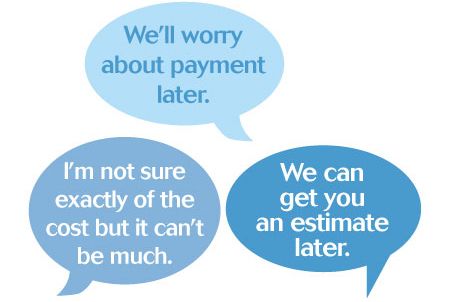

Ignoring the invoice

Most veterinarians hate mentioning the "M" word (money) to clients. We suspect it sullies our image, diminishes our authority and encumbers our empathy. Well, it doesn't—unless you let it. Delaying the cost conversation typically leads to disgruntlement and dissatisfaction.

Be upfront about costs. If you don't know how much something costs, find out. If you guess, chances are you'll err on the lower side and the client will feel cheated when the bill is higher. Worse, you usually wind up honoring the incorrect estimate and eating the costs, which chips away at your own bottom line. Clients understand that good medical care costs money, but they need to know how much so they can share in making decisions. The client must be involved in all decisions. The sooner money is confronted, the sooner your team can begin your patient.

I fully understand that not all clients will be offended, upset or even notice these spoken slips. Not everyone will agree that they're gaffes or even inappropriate. I get it. What I do hope is that you're inspired to be a little more aware of the words and phrases you use during everyday conversations. Body language can help you avoid negative repercussions from some phrases, and it is true that some phrases are worse written down than spoken. But bad is bad—and we want to be good.

Veterinary Economics Editorial Advisory Board member Dr. Ernie Ward is an author, speaker and practices at Seaside Animal Care in Calabash, N.C., a National Practice of Excellence Award winner.