Guide your employees to better performance

Sometimes these employees are simply in the wrong job. If so, just redeploy them.

SO YOU'VE FOUND THE PERFECT TECHNICIAN, and things are going great. Then, a few months go by, and her performance starts to slip. She's late to work, calls in sick, doesn't follow directions well, and falls behind on her duties during your appointments. Unfortunately, you're likely more comfortable managing that horse you're vaccinating than that employee who's digging through the truck, looking for the syringes you asked her to pack earlier. But part of your job as a practice owner is to manage your staff members' performance.

To do that, you need to explain your expectations clearly. Then, when a problem comes up, you need to address it promptly—and document your conversation so there's a clear paper trail if you ever reach the point that you need to terminate an employee. After all, says Dori Villalon, executive director of the Cleveland Animal Protective League, "Conversations that weren't documented didn't happen." Here's a closer look at how you can better manage your employees' performance.

Setting expectations

First, you must tell your employees what you expect. Your best strategy: Put your expectations in writing, says Villalon. At the Cleveland Animal Protective League, new employees sign an expectations document, which the Dumb Friends League shared with Villalon, among other human resources tips. The document says, in part:

Preparing a written warning

We have the right to expect that you will attend work regularly, on time, and give a day's work for a day's pay as well as respond positively to direction, get along with co-workers and clients, and adhere to the policies and procedures of the Cleveland Animal Protective League. We have the right to discipline you if you violate this agreement.

The bottom line

You have the right to expect that the Cleveland Animal Protective League will provide safe working conditions, fair treatment, responsible leadership and consistent responses to rule violations. You have a right to know what is expected from you, as well as what the consequences are for not meeting those expectations.

In addition, all new employees sign a code of professional ethics, which outlines the organization's commitment to maintaining a professional work environment and a positive community image. By signing, employees agree to follow all policies and procedures, inform supervisors when policies aren't being followed, and engage in direct communication. "Not reporting violations is wrong," says Villalon.

Her employees also agree not to engage in malicious or speculative talk among co-workers. "It's unproductive, undermines our ethical standards, and won't be tolerated," she states.

She also hands out an employee manual that covers dress code, use of company vehicles, smoking rules, parking-lot guidelines, and other cultural points. While this level of detail may seem like overkill, Villalon says you can't assume employees know what you want them to wear, say, or do. "Tell them," she says.

Every job description at the Cleveland Animal Protective League includes the projects for which that position is responsible and lists measures of accomplishment so employees know what standards they're expected to meet. For example, the position of animal caretaker at an equine hospital might be held accountable for barn cleaning. The measures of accomplishment: timeliness, cleanliness, safety, and compliance with operating procedures.

Address problems promptly

When job expectations aren't met, Villalon recommends addressing the problem promptly. Of course, regular performance evaluations should be a part of every supervisor's tool kit, but you also need a policy for quickly handling such common performance problems as tardiness, poor attendance, failure to perform duties as instructed, personal hygiene issues, disregard for safety, and conflict between employees. Equine practices may also see a technician providing free advice to a client outside the veterinarian-client-patient relationship, handling horses in an unsafe manner, or refusing to cooperate with the receptionist to schedule farm calls.

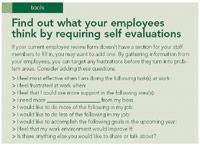

Find out what your employees think by requiring self evaluations

Villalon follows these steps to resolve performance problems:

1. Cool off. "The more potential for the conversation to become heated, the more important it is that you're prepared to stay calm," she says.

You said what?

2. Counsel in private. Schedule a time—sooner rather than later—to meet privately with the staff member. The only exception: There should be a witness if you're terminating an employee. Otherwise, Villalon encourages employers to praise in public and criticize in private.

3. Be humane and professional. Sit next to the employee rather than behind your desk, maintain eye contact with the person, have tissue available, and, in general, be kind.

4. Use "I" statements instead of "you" statements. Saying, "I'm feeling concerned about the way some horses are being handled lately," is better than saying, "You're going to get somebody hurt if you don't start handling these horses properly."

5. Show how the employee's behavior affects others. Saying, "When you schedule farm calls for one of the doctors and don't write it in the appointment book, the receptionist doesn't know which time slots are filled," may help the staff member realize how her actions affect others' work.

6. Remind the employee of his or her knowledge of your expectations. Revisit those documents that outline the job description, your expectations about team members' work and behavior, and code of ethics. If applicable, pull statements directly from them to remind employees what they agreed to. For example, you might say, "As you know from the job description, we expect technicians to help educate owners about horse health, but we also expect that you won't diagnose or treat conditions on your own."

7. Ask how you can help, and agree on a plan of action. Close the meeting by offering to help the employee get back on track. And outline the consequences if the employee doesn't improve. Finally, ask for an agreement that he or she understands what's been said and will make adjustments. If this is your second or third conversation on the same subject, prepare a written document that outlines the problem and your proposed course of action. Ask the employee to sign the document, and put it in his or her file.

Making a paper trail

Villalon likes to maintain a supervisor's file on all employees in addition to their regular personnel file. She records all discussions, remarks, and behaviors that may be important. For example, a first conversation with an employee about not re-stocking the ambulatory vehicle on its return to the clinic would be recorded in her supervisor's file for that employee as a verbal warning. A second conversation about re-stocking would result in a written warning that the employee would initial or sign and would be included in his or her regular personnel file. A third conversation about re-stocking could lead to termination.

Suggested reading for supervisors

"Each time, document why you met, when you met, who was there, and what was said or done," she says. "Having a paper trail of warning documentation may help ward off claims of discrimination or unfair termination."

Villalon also recommends keeping track of improvement, special effort, and client comments in the supervisor's file. These notes will be helpful when you prepare evaluations.

Knowing when firing's the right choice

Sometimes an employee commits an act, such as embezzlement, that's so egregious that you must fire him or her immediately. Other times, an employee either can't or won't comply with your standards, and you can use the three-strikes-you're-out method described above.

But what about the employee who performs well but is always late? Or the receptionist who's been with you 20 years, but refuses to learn how to use the new computer system?

"Admit that some employees are holding you back," urges Villalon. "And take action. Address the issue with them, and give them an opportunity to grow. If they stay and improve, great. And if they decide that your practice is no longer a good fit for them, that's probably fine, too."

Sometimes these employees are simply in the wrong job. In these cases, just redeploy them to an existing position that's a better fit. "But don't create a job for them," she cautions, "unless you really need a new position to fulfill certain job functions."

If these options don't work, then bite the bullet and fire the employee. Villalon recommends preparing a termination checklist that you can follow when it's time to let an employee go. Such situations are often difficult and having a clear-cut list of what you need to do will make things easier, she says.

"Again, at this point you want a clear paper trail that shows that you gave the employee a fair chance to meet your expectations," says Villalon. "When the time comes to fire, you're really done talking about the issue. So if your employee pleads for his or her job or starts to argue, just keep saying, 'I've made my decision.' You don't want to prolong the pain at this point."

Like many aspects of personnel management, addressing performance problems requires good communication skills. These are some of the hardest situations you face as a supervisor. But you can at least feel more prepared to tackle this challenge. So follow the advice given here and seek additional training to fill in any gaps in your skills. And make team leadership a new area of strength.

Veterinary Economics Editorial Advisory Board member Dr. Lydia F. Gray, MA, is a consultant in Elburn, Ill. Please send questions or comments to: ve@advanstar.com

Dr. Lydia F. Gray, MA