I survived: Managing a veterinary practice merger

We experienced headaches, setbacks, and eventually practice success.

More than 12 years ago, I first read about veterinary practice mergers in

Veterinary Economics

. Since then, industry enthusiasm for mergers has been eclipsed by the popularity of corporate acquisitions. Either business move can be enticing to small animal practitioners who want to streamline operations, grow business, and add more expensive and sophisticated equipment.

Both models centralize management operations, enabling practitioners to return to full-time medical duties, and can provide a possible exit strategy for retirement. But of the two, I believe a merger is preferable to selling to a corporation because partners retain more control over their business. The process isn't without hard work and difficult decisions, but a successful merger is possible and can be very rewarding.

The first step: compatibility

In 2000, I began meeting with a colleague who owned a companion animal hospital just a few blocks from my hospital. We'd been sharing emergency calls and attending continuing education meetings together, and we understood each other's client base, competency level, and practice philosophy. From time to time we would meet for lunch. These meetings started off as gripe sessions. We'd both outgrown our facilities and wished to continue adding capacity and equipment for new and expanded services. Eventually our discussions turned to the possibility of merging. We could combine practice assets to save money and continue growing our client bases.

In time we brought his associate and my partner into the discussions and developed a plan to form a four-person partnership. The merger would be an opportunity to streamline operations, move into a larger shared facility, and consolidate equipment, supplies, and staff.

Thinking through prospective roles

We were all four general practitioners and active in the community and profession. One had training in ultrasonography and an interest in orthopedics; another enjoyed internal medicine as well as orthopedics. One was a whiz at interpreting laboratory test results and was trained in performing endoscopic procedures. The fourth had a special interest in dentistry. We thought the mix of interests and personalities was good. Although we would eventually hire a practice manager to help us navigate the maze of regulations, benefit plans, policy manuals, and personnel issues, one of the partners would have to be available to sign off on policies and oversee the human resources issues. We also needed a point person for the myriad of discussions with the attorneys, accountants, bankers, architects, contractors, and city officials. Since I had earned an MBA, I became that person.

Establishing a workable structure

We established a production-based compensation system for the doctors. Since that wouldn't account for the time I would have to be out of the exam room and surgery suite to deal with business-related problems and questions, we established another level of compensation for management. Under the guidance of a consultant with extensive knowledge of veterinary medicine and accounting systems, we set up three companies: the animal practice subchapter S corporation, a C corporation to develop the property and manage the new hospital construction, and an LLC to own the real estate. The structure was confusing and cumbersome to establish, but it has served us well. We are partners in all three companies.

At the same time that we were forming the three new companies, we also hired new management assistance and started a building project, so our merger was a multilevel project. The process was long, stressful, and tedious, but at the same time invigorating and exciting. After two years of working with a consultant, a lawyer, a banker, and a CPA, finally, on August 1, 2002, Augusta/Valley Animal Hospital Inc. was formed.

Finding the right facility

Ideally, in a merger of hospitals in close proximity, one hospital closes and consolidates into the other facility. That immediately cuts the overhead expenses-you pay one rent instead of two, one utility bill instead of two, and so on. As we'd already outgrown both facilities, this wasn't an option. We were both landlocked by neighboring establishments. We couldn't purchase acceptable adjacent property to add onto existing buildings. Therefore, we were forced to look for a larger existing building we could adapt or a piece of land on which to erect a new structure.

After exploring a number of options, we purchased a 15,000-square-foot former auto parts warehouse located behind one of the hospitals. The 20-year-old building was primarily a shell, which meant there would be minimal demolition. We knew some of the metal exterior walls would have to go, but the roof and superstructure were in good condition. We only needed 10,000 square feet for the hospital and boarding kennel, but we hoped to rent out the remaining 5,000 square feet. We also were able to acquire an adjacent lot for future growth.

Our design technique was pretty basic. We drew a rectangle on a sheet of notebook paper and started sketching in where we wanted doors, walls, and bathrooms. Each of the partners was given an opportunity to request anything he or she wanted. Of course, we were also looking at floor plans in books and magazines and visiting other animal hospitals to get ideas. Once we had what we thought was a good floor plan, we turned the drawing over to an architect to formalize the design.

Our builder was a local contracting firm I'd used previously for some renovation projects. The company had also built another animal hospital and had renovated a shopping center space for our local emergency clinic. This firm had a good reputation for being reliable, and they didn't disappoint. They showed up when they said they would and, once the project was started, stayed with it until completion. Soon our new space was alive with activity, a flurry of hammers and saws at work.

Inevitable construction problems

Any construction project brings unexpected problems, and ours was no different as we worked through a maze of building permits and licenses. We included an efficiency apartment in one corner of the building to accommodate veterinary student externs. This necessitated a special use permit from the city. All plans and revisions had to go through the city building inspector's office, which was time-consuming and tedious.

We'd decided on an in-state architectural firm that had done some renovation work for two local veterinary hospitals. However, the firm hadn't worked with or drawn a plan for a veterinary facility to be built from the ground up. I found myself doing much of the research about building materials for animal hospitals to ensure ease of cleaning and sanitation. For example, air exchanges needed to be planned to keep odors under control. If I were starting over, I would look more seriously at architects who have extensive experience with veterinary facilities, even if their offices are located in other parts of the country. The HVAC system in our new facility was so flawed it took a local heating contractor a full year to correct all the design errors.

Hiring key support staff

As I've mentioned, our first change to the staff was to hire a practice manager. Our goal was for this person to oversee the details of merging two systems and policies into one combined entity. Since the official merger occurred almost two years before anyone moved into the new building, the manager split her time between the two hospitals. She established office hours at both facilities and carried her computer and files back and forth. With equal time at each hospital, she became familiar with the personalities and work habits of all team members. This was especially beneficial to working together after the merger, and I regret that we didn't encourage more employees to do the same. Physically moving all the doctors and employees into the new building took almost two years, and when we did finally all come together, there was friction among the support staff. They didn't know each other or the different procedures used by the two hospitals.

The practice manager was meticulous in organizing job descriptions, policies, and procedures. She was tireless when it came to interviewing vendors about computer systems, filing systems, and office furniture. Her attention to detail was often exasperating, but it's what helped her get the job done right the first time. An added bonus was her knowledge and skill in bookkeeping, as she set up three sets of books for the three companies.

Working through team conflict

At the new facility, we extended the office hours, which meant everyone, including the doctors, had to deal with schedule changes. Most were relatively minor, but some people had special needs, such as childcare and transportation problems. These issues were settled with patience and some give-and-take on everyone's part.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect for our employees was trying to work through the changes brought about by the merger without letting emotions get out of hand. We set up teams and used a balanced scorecard approach to solving problems and establishing procedures. We did, however, lose staff members because of the merger. One technician became overwhelmed by the responsibility of merging inventories from both hospitals. A customer service representative was not able to take direction from the new manager and tried to undermine cooperation. One manager-technician left because she lost some job responsibilities when the new manager came on board.

And, of course, we faced a major “us versus them” attitude. Each of the hospitals employed committed and loyal staff members, some of whom had been on board for years, so even the most basic duties-filing records, recording laboratory results, inputting charges-became emotional touch points. We dealt with passive aggression on a weekly basis. Turf wars developed over some supposedly minor decisions such as where to store instruments and dog food and how to arrange the laboratory machines. There were seemingly endless discussions about what forms needed to be revised and in what order they should be placed in the patient file. It took three years to work the phrase “That's not the way we did it” out of the staff vocabulary.

Clients' reaction to the change

Based on our experience, clients fall into one of two camps when faced with choosing a new animal hospital for their pets. One type of client finds it a pleasure and a comfort to bring pets into a modern facility with the newest and best equipment and a large staff with multiple skills and levels of knowledge, experience, and expertise. At the other end of the spectrum is the client who's intimidated by change and equates larger space with increased costs for care.

Both hospitals had previously been small facilities with relatively small staffs. Almost every client who came into one of the smaller hospitals would get to know all the members of the staff because the work areas mixed with the client areas. Although surgery was out of the traffic flow, the exam rooms, laboratory, and animal areas were by necessity easily seen and accessed by almost everyone who came in the door.

The new facility, by contrast, is roomy and spread out. The departments are formally separated by walls and doors. Employees communicate by private phone or intercom instead of face to face. If technicians are assigned to surgery, radiology, or laboratory for the day, they may treat multiple patients without ever coming into contact with a client.

Since we're open more hours at the new facility, clients may see different assistants or doctors at each visit. Having multiple doctors on staff assures easy access to veterinary care, but it can take a toll on client relationships. The lack of consistency decreases intimacy and clients' familiarity with the staff. This is a major hurdle to overcome, and in some cases, it can't be remedied. Yes, we lost some clients. Providing exceptional care and monetary value is a balancing act for practices.

Improved patient care

Patient care is without a doubt measurably better in the new merged facility. We were able to select the best equipment from each hospital to bring into the new practice. We've also been able to upgrade equipment as the need for new procedures has arisen. There's some redundancy with surgical instruments and equipment in certain areas of the hospital, but when the caseload is large and there's little time to clean instruments between cases, the extra equipment comes in handy.

I find the collegiality among our doctors reassuring, especially when one of us is dealing with difficult cases or intricate procedures. Clients and doctors alike appreciate having access within a few moments to an additional opinion or skill set. We can resolve difficult questions and treatment regimes in a few moments' huddle over a laboratory report or radiographic study. Plus, there's no comparison to the peace of mind we all experience when the weekend comes, knowing that while we're on the golf course or trout stream, our patients are being monitored and cared for by a colleague who'll do whatever's necessary to ensure the best outcome. It's also gratifying to know that we have enough team members to provide follow-through with elaborate treatment plans and nursing care. We use the local emergency clinic for cases that need 24-hour care, but some patients are fine in our hospital overnight or over the weekend, since we can share the responsibility of coverage.

Because we have a larger facility, we're able to provide specialized services on a referral basis for other hospitals in area. We have an ophthalmologist on board one day a month, a dermatologist two times a month, a dentist two times a month, and an acupuncturist twice a month. Many of their cases are referred by area veterinarians.

Slower-than-expected financial gain

One of Murphy's Laws states, “It always costs more than it costs.” That was certainly the case with our project. We made a business plan with timetables, budget projections, and cost estimates for organizational expenses and construction. When I took our portfolio to three banks, all three offered us favorable financing. When we got into the project, however, the costs mounted very quickly. We had to go back to the bank twice. Each time our lender was understanding and accepted our revisions and increased needs, but the changes took their toll our bottom line.

Operating a large, modern veterinary hospital isn't cheap. The utility bills for a facility with pleasant, spacious exam rooms, multiple treatment areas, and roomy surgery suites can seem staggering compared with a cramped facility one-fourth the size. Even if the staff is meticulous with sanitation and cleanliness during and after procedures, someone must be available during down hours to sweep, mop, and wipe down flat surfaces. Landscaping must now be done by professionals. In addition, the 5,000 square feet we'd planned to rent wasn't filled for some time.

Going into this project, we were told by experienced people that it would be three years before we saw financial benefit. It's actually taken us five years to see a profit. We're still burdened with long-term debt that at times seems overwhelming, and we agonize over accounts payable at certain times of the year, depending on fluctuations in the economy. Our consolation is in working in a state-of-the-art facility and knowing we're investing our lives in a growing venture.

We didn't decrease staff size or payroll with the merger. In fact, since we were able to expand our services and hours, we have more staff now than we did in the two smaller hospitals. Not only that, our staff now is more skilled, more knowledgeable, and more highly paid than before the merger. We select and keep only the best, most motivated workers because we feel we deserve the best assistance in providing patient care and our patients deserve the most conscientious caregivers.

Was a merger the right decision?

I would absolutely do the merger again. The business model is valid and I think future economics will inspire more small practices to consider consolidation. In recent years, practitioners have seemed more willing to work together. I see less jealousy and mistrust when everyone involved has the best care of the patient at heart. Though the process requires hard work and some difficult decisions, a successful merger can be very rewarding. The availability of proper equipment and staff ensures the veterinarian that he or she is able to practice high-quality medicine and find fulfillment in a busy profession.

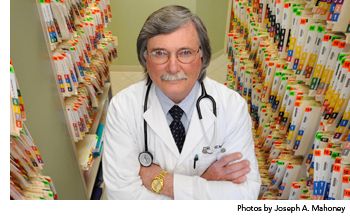

Dr. Donald Henry, MBA, is co-owner of Augusta/Valley Animal Hospital in Staunton, Va.