Pets, Vets, and Opioids

Remaining knowledgeable and observing relevant legal requirements will enable veterinarians to be strong advocates for the responsible use of opioids.

Strange Cast of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, written by Robert Louis Stevensen, describes a medical doctor who swallows a potion that transforms him from a rational, intelligent human into an evil monster. Although it was written in 1886, the novella strikes an ominous chord today. Opioids—the modern equivalent of the doctor’s potion—can create dependency, transform people into strangers sometimes given to harmful deeds, and bring on the distinct possibility of death.

Today’s nationwide opioid epidemic is turning families and entire communities upside down. The most recent report from the American Society of Addiction Medicine states that prescription medication overdose is the leading cause of accidental death among people under 50. The group also noted that opioid addiction is driving this epidemic, with over 20,000 overdose deaths related to prescription pain relievers in 2015.1

Opioids in Veterinary Medicine

How does this very human problem relate to the veterinary profession? After all, veterinarians prescribe opioids for animals—period. “They cannot and do not prescribe for people,” said Larry J. Nieman, DVM, co-owner of the veterinary consulting firm Essential Elements. Licensed in 6 states, Dr. Nieman has been a veterinary clinician for 42 years and has had a Controlled Dangerous Substance license from the US Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). He is past president of the Connecticut Veterinary Medical Society and served on the legislative council of the Oklahoma Medical Association.

RELATED:

- Treating Joint Pain With Tramadol

- Effectiveness of Transdermal Lidocaine After Canine Ovariohysterectomy

Veterinarians are not a part of the problem, Dr. Nieman said, and they typically do not prescribe the most commonly abused opioids, such as oxycodone and fentanyl.

Still, the opioid epidemic does affect animals, their owners, and even veterinary teams. Recent reports and expert insight show clearly how this crisis affects today's veterinarians.

Abuse Among Pet Owners

The most common opioid carried by veterinary practices and targeted by addicts is tramadol, which is prescribed to both animals and humans. There have been just enough reports of abuse or misuse to cause concern and prompt some states to increase regulations. Last fall, for example, following an investigation by the research firm Aurelius Value, the website Mercola reported that PetMed Express (also known as 1-800-PetMeds) was accused of selling pet opioids for use in people.2 PetMed Express denied the allegation.

Then there is the issue of pet owners supporting their own addictions by taking medications intended for their pets. In a 2017 NBC News report, David Gurzak, DVM, an associate at Brackett Street Veterinary Clinic in Portland, Maine, said that to him, the first sign that something is amiss is when a pet owner asks for a drug by name.3 He recalled a client who repeatedly requested a prescription for tramadol. “It was for a dog that had a condition...that normally would not require any medication at all,” Dr. Gurzak said. “I suspected that she was using it herself.”

Eli Landry, DVM, CVA, owner of Seminole Veterinary Hospital in Oklahoma, reported seeing pet owners coming into the practice looking for opioids for themselves. “Generally,” he said, “it’s a new client we’ve never seen before who comes with an old patient, and they’ll ask for the drugs by name, like ‘Oh, my ailing and aging dog really needs some tramadol for his lame leg.’”3

In a report on Florida’s WPBF News, Lisa Ciucci, DVM, owner of Gardens Animal Hospital in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, told the reporter about “blacklisted” clients who go from veterinarian to veterinarian seeking medications such as tramadol, Xanax, and Valium by name.4 Some owners give excuses for why they need another refill of pills, such as spilling them on the floor, she said, while others go so far as to physically harm their pets to get a new prescription.

Jim Arnold, chief of policy and liaison for the DEA’s Diversion Control Division, told the New York Post: “They’ve gotten very sophisticated in how they obtain drugs and go about their activities...It’s an area that allows drug seekers to fly under the radar. We know it’s happening, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a lot more activity than we’re aware of.”5

Tramadol, prescribed for both pets and people, is the

opioid carried by veterinary practices.

Marsha Mercer reported in The Washington Post in September 2017, “Last year in Virginia, a dog owner took his boxer to 6 veterinarians to get antianxiety pills and painkillers for his own use before he was caught.” Eventually, according to Fairfax County police, the owner was charged with prescription fraud. Mercer also reported on other cases: “In Kentucky in 2014, a woman was accused of cutting her golden retriever twice with a razor so she could get drugs. And in the early 2000s, an Ohio man allegedly taught his dog to cough on cue so the owner could buy hydrocodone.”6

The Potential for Pet Overdose

Another concern for veterinarians: the risk of accidental opioid overdose in pets. In a bizarre but true story from New Hampshire, a 3-month-old puppy named Zoey ingested an opioid while on a walk with her owner around her neighborhood. Zoey was rushed to the hospital and given naloxone to revive her. The hospital owner, pleased with the outcome, noted that the incident indicates the extent of the opioid crisis.7

Abuse by Veterinary Practice Employees

The rampant abuse of opioids creates yet another risk: staff access to these drugs, according to Kimberly Hammer, VMD, DACVIM (SAIM), a medical director at NorthStar Vets Veterinary Emergency Trauma & Specialty Center in Robbinsville, New Jersey. Checks and balances within a veterinary hospital are essential with respect to ordering, storage, administration, and dispensing for the health and protection of the staff, as well as the legal protection of the doctor and hospital, Dr. Hammer said.

Legal Responses

The opioid epidemic has prompted many states to sign control measures into law. In Maine, for example, professionals—including veterinarians—who can prescribe drugs are required to check a statewide database called the Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) before prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines. This measure ensures that doctors notify the proper authorities if certain criteria are met when a patient comes in and has reason to leave with opioids.

Other states have variations of the PMP and are passing legislation with more stringent requirements for dispensing and reporting opioid prescriptions. For example, a New Jersey law limits initial opioid prescriptions to a 5-day supply, one of the strictest prescribing limits in the country.8 Pharmacies in the Garden State are required to report prescription data that is shared with 14 other states. Guidelines related to the legislation urge veterinarians who prescribe potentially addictive opioids, such as tramadol and oxycodone, to use the New Jersey PMP.9 Nine other states, including New York and Massachusetts, have legislation that limits opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less.10 A review of current prescription drug abuse legislation in the United States can be found on the National Conference of State Legislatures website.11 Pushback Among Veterinarians

The Maine Veterinary Medical Association (MVMA) put out a position statement against the state’s PMP law, writing that while the “opioid epidemic is a serious public health crisis that requires all prescribers and dispensers of opioids and benzodiazepines to assist in preventing the misuse or diversion of these drugs, [veterinarians] are ineffective participants in reducing drug abuse by the public [because they] do not have the human medical exposure or back- ground to review medical prescription information for animal owners.” In an interview with American Veterinarian®, Katherine Soverel, executive director of the MVMA, said that including veteri- narians could dilute the data and make the PMPs less effective.

Having advocated for veterinarians to have a seat at the table when such laws are drafted, Soverel is now working to change the law as it pertains to veterinarians. A bill under consideration in Maine would exempt veterinarians from the PMP and expand the types of continuing education (CE) that would meet the current requirements. The MVMA strongly supports this bill, according to Soverel. New Hampshire veterinarians who share that view worked successfully to get their state legislature to pass a revised bill exempting veterinarians from PMP requirements.3

“I’m a veterinarian, not a physician. I shouldn't have access to a human's medical history,” said Kevin Lazarcheff, DVM, president of the California Veterinary Medical Association. He objects to checking a client’s use of controlled substances and points out that there is no protocol directing veterinarians if they suspect that a client is abusing drugs.6

Amanda Bisol, VMD, director and legislative chair for MVMA, knows well that many consider the new legislation unfair to their profession, but she says veterinarians should take the problem seriously and consider how they can help. She urges veterinarians to look for a balance of drugs for in-hospital use, including drug classes such as nonopioid analgesics and steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. When prescribing opioids for external use, she said, veterinarians should make sure they understand and comply with the strictest state and federal standards. Even if they seem too strict, she said, veterinarians must comply. “It’s better to be part of the solution than to risk being a part of the problem,” she said.

Training Response

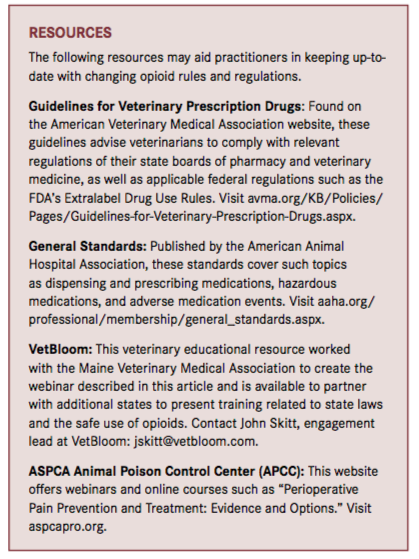

Veterinarians in all states need to be aware of new legislation—including laws under consideration—regarding the use and prescription of opioids, which might entail training. Maine’s new law requires that veterinarians, along with other prescribers and dispensers of opioids, receive 3 hours of opioid CE every 2 years. As a result, MVMA has partnered with VetBloom, an educational platform owned by Ethos Veterinary Health, a network of hospitals providing specialty and emergency pet care. Directed by Patrick Welch, DVM, MBA, DACVO, VetBloom developed a variety of curricula to meet the needs of veterinarians in New England. Completing an online webinar, created for and with MVMA, enables MVMA members to maintain their state license.

The course consists of 2 sections. The first, created by Dr. Bisol, outlines what state-licensed veterinarians must do comply with the law. The second section is divided into 2 parts; the first deals with the safety and use of opioids. Created by Andrea Looney, DVM, DACVAA, DACVSMR, CCRP, an anesthesiologist with Ethos Veterinary Health, it addresses definitions related to opioid use in veterinary patients, including:

- What drugs constitute agonists and antagonists

- Opioid indications and contraindications

- How receptors and receptor subtypes translate into physiologic and pharmacologic effects

- How opioids are used in premedication, local blocks, postoperative and intensive care continuous-rate infusions, and in-home chronic care

The second part, developed by Jennifer Kelleher, PharmD, BCPS, FSVHP, formerly with Ethos and now a compounding pharmacist and educator, describes the legal nuances and recommendations for administering opioids in a veterinary clinic. It explains the requirements and considerations for dispensing opioids to clients, covers the steps for prescribing Schedule II—IV opioids using the Maine PMP, and discusses the requirements for electronic, hard-copy, telephone, and faxed opioid prescriptions in the state.

Other Learning

Beyond being aware of the legalities, veterinarians must understand the everyday practicalities of when and why opioids are recommended and how to avoid problems.

The most common reason cited by veterinarians for avoiding the use of opioids is the fear of adverse effects, according to Mark E. Epstein, DVM, DABVP, CVPP, director at Carolinas Animal Pain Management and TotalBond Veterinary Hospital in Gastonia, North Carolina.12 He advises veterinarians to understand how these drugs work within the peripheral and central nervous system and how to recognize and treat potential adverse effects. Veterinarians should be knowledgeable about 3 general drug categories, he said:

- Pure mu agonists (strong opioids), such as morphine and fentanyl

- Partial mu agonists and agonist-antagonists (weak opioids), such as buprenorphine and butorphanol

- Mu antagonists (reversal agents), such as naloxone, which are used in cases of overdose or severe adverse effects

With new drugs being introduced constantly, veterinarians must stay current, Dr. Epstein said. Tapentadol, for example, a new class of analgesic for humans, has shown some utility in animal models. A sustained-released injectable buprenorphine may be available soon, as well.

Conclusion

Even veterinarians who feel removed from the opioid crisis would be well served to become knowledgeable about and comfortable with the use of these drugs. By staying current with local, state, and national laws, veterinarians can be strong advocates for the responsible use of opioids and an important part of the conversation around the epidemic.

Dr. Shadle earned her PhD in interpersonal and organizational communication from the State University of New York at Buffalo. Dr. Meyer earned his PhD in communication studies and speech arts from the University of Minnesota. They write and train through Interpersonal Communication Services, Inc. (veterinariancommunication.com). They have trained veterinary professionals at numerous national and international conferences.

References:

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 20l6;65(5051):1445-1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1.

- Mercola J. Is PetMed selling opiates for people, not pets? Mercola website. articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2017/09/12/petmed-selling-opiates.aspx. Published September 12, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Edelman A. Pet connection: opioid addicts score drugs from the local vet. NBC News website. nbcnews.com/news/us-news/pet-connection-opioid-addicts-score-drugs-local-vet-n798211. Published September 3, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Kelly M. Opioid addicts turn to pet medications to get high. WPBF News website. wpbf.com/article/opioid-addicts-turn-to-pet-medications-to-get-high/10274777. Published July 9, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Morgan R. People are now maiming their pets to score drugs. New York Post website. nypost.com/2017/01/16/people-are-now-maiming-their-pets-to-score-drugs/. Published January 16, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Mercer M. When addicts steal their pet’s painkillers, what’s a vet to do? The Washington Post website. washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/when-addicts-steal-their-pets-painkillers-whats-a-vet-to-do/2017/09/15/009c5956-8cd4-11e7-91d5-ab4e4bb76a3a_story.html?utm_term=.f189f824afc9. Published September 16, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Bode K. Puppy overdoses after ingesting opioid on morning walk. Eagle-Tribune website. eagletribune.com/news/merrimack_valley/puppy-overdoses-after-ingesting-opioid-on-morning-walk/article_83b24095-9294-54b1-a62d-81971efc54dd.html. Published October 24, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Gregory J. New Jersey law limits initial opioid prescriptions to five days. HealthExec website. healthexec.com/topics/care-delivery/nj-law-limits-initial-opioid-prescriptions-five-days. Published February 16, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- King K. New Jersey seeks to expand opioid prescription monitoring to veterinarians. Wall Street Journal website. cetusnews.com/news/New-Jersey-Seeks-to-Expand-Opioid-Prescription-Monitoring-to-Veterinarians-.ryl-3cVhhW.html. Published October 11, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- O’Shea T. New Jersey enacts strict opioid prescribing law. Pharmacy Times website. pharmacytimes.com/contributor/timothy-o-shea/2017/02/new-jersey-enacts-strict-opioid-prescribing-law. Published February 20, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Prevention of prescription drug overdose and abuse. National Conference of State Legislatures website. ncsl.org/research/health/prevention-of-prescription-drug-overdose-and-abuse.aspx. Published May 23, 2016. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Epstein M. CVC highlight: opioids: the good, the bad, and the future. DVM360 website. veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/cvc-highlight-opioids-good-bad-and-future. Published December 1, 2011. Accessed February 15, 2018.