WVC 2018: Global Guidelines Put Dental Health in the Spotlight

This universal guide strives to provide clarity in an area of veterinary medicine that is widely ignored and subject to many myths and misconceptions.

Dental disease is among the most common medical issues in small animal medicine, yet oral health traditionally has been one of the most underserved areas in the veterinary field. Not only is it overlooked or underemphasized, but veterinarians also have not accepted a universal standard of care or adopted a singular mindset when it comes to treating patients and educating clients about dental disease.

Practitioners tend to give the topic short shrift. For example, the importance of early intervention to combat osteoarthritis is widely accepted, but preventive oral care is nearly nonexistent in some practices. Although veterinarians agree on the importance of engaging in discussions with clients about the ramifications of pet obesity, many experts have long disputed the level of pain associated with oral decay.

RELATED:

- One Tooth at a Time

- Myth: Dental Pain Doesn't Hurt Animals

To combat misinformation and ultimately improve the lives of animals, the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) released a comprehensive set of global dental guidelines in fall 2017. The 161-page document is divided into 9 sections that aim to support veterinarians worldwide in improving recognition of dental disease, understanding best practices for treatment, and creating realistic minimum standards for dental care. Digital copies can be downloaded from the WSAVA website.

Multiple sessions covering the guidelines were presented at Western Veterinary Conference in Las Vegas, Nevada, led by dental specialist Brook A. Niemiec, DVM, DAVDC, DEVDC, FAVD, chief of staff at Veterinary Dental Specialties & Oral Surgery in San Diego, California, and animal welfare author and speaker Kymberley Stewart, DVM—both of whom were instrumental in creating the guidelines. American Veterinarian® interviewed these 2 experts at the conference to find out more about the guidelines and how they can be used to improve practice and patient welfare.

“The guidelines, first and foremost, were created to bridge the gap of a lack of knowledge,” Dr. Niemiec said. “There is a lack of knowledge in veterinary dentistry.”

He attributes much of the misinformation to a shortage of dental curriculum in veterinary schools. When recent graduates learn about dentistry, he said, it is often from doctors who didn’t properly learn about it during their own schooling 20 years earlier. “This ongoing cycle has resulted in a subpar level of care,” Dr. Niemiec said.

“Dentistry is probably one of the most important areas for standardization because it is practiced so differently and taught so differently everywhere—if it’s taught at all,” Dr. Stewart added.

The guidelines’ protocols were developed by a committee of WSAVA members that included veterinary dentists from North America, South America, Africa, Europe, and Australia, as well as experts in academia, anesthesiology, nutrition, and animal welfare advocacy and representatives from WSAVA’s other global-focused committees. They applied their varying areas of expertise to address many of the common misconceptions associated with oral health and provide practice standards to improve the overall quality of care companion animals receive.

Periodontal Disease

In addition to being one of the most common ailments among animals, periodontal disease spreads quickly and can affect seemingly unrelated body systems. To ensure that all veterinarians share a basic understanding of oral disease and how it progresses, the guidelines provide general knowledge of dental anatomy and physiology. The first section features a breakdown of the bones, nerves, and blood systems associated with the mouth, aided by images and tables that enrich the text.

The guidelines illustrate the quick and serious progression of oral decay: Plaque forms within 24 hours; calculus, within 3 days; gingivitis sets in as early as 2 weeks. Left untreated, periodontal infections have been linked to diabetes mellitus; heart, lung, liver, and kidney disease; and even early mortality. These facts are well supported by research and similarities in comparative medicine—including in humans—but are not widely understood by veterinarians.

Pain Associated With Dental Ailments

Central to the guidelines is a discussion about the level of pain experienced by animals with dental disease or injuries. According to Dr. Stewart, dentistry is one of the least addressed areas regarding animal welfare because veterinarians have wrongly been taught that these conditions don’t hurt or that simply monitoring the affected area is an acceptable standard of care. “We wouldn’t watch an animal with a broken leg, yet we watch an animal exist every day with a broken tooth,” she said. “To the animal, pain is pain.”

Many veterinarians assume that because a dog with a broken tooth continues to eat, the animal is not in pain, Dr. Niemiec said. However, animals know they need to eat to survive and will do so regardless of oral discomfort.

It is well documented in comparative species—rodents and humans—that fractured teeth, infected teeth and gums, and impacted teeth start to ache over time, Dr. Stewart added. “As more specialists in a variety of areas investigate how animals display pain, we’re discovering that perhaps they tell us they hurt in ways we wouldn’t expect, in ways that aren’t intuitive to us as humans,” she said.

Drs. Niemiec and Stewart, along with the other experts who collaborated on the guidelines, hope veterinarians will now better understand the need to address the misconception that oral ailments don’t hurt and work to alleviate the pain—and that veterinarians who rethink their current therapies will become better advocates for their patients.

Anesthesia Is a Must

Another crucial takeaway from the guideline is that anesthesia is an integral part of veterinary dentistry. “There is not a veterinary dentist in the world [who] would say anesthesia-free dentistry is acceptable,” Dr. Niemiec said—but noted that this consensus follows a decades-long battle.

“If you don’t provide an oral cleaning under anesthesia, then you’re only scaling the surface of the teeth, which does nothing for the pet,” he continued. What appears to be a clean mouth may in fact be riddled with gum disease. “I’ve performed extractions on teeth that are perfectly clean but horribly diseased,” Dr. Niemiec said.

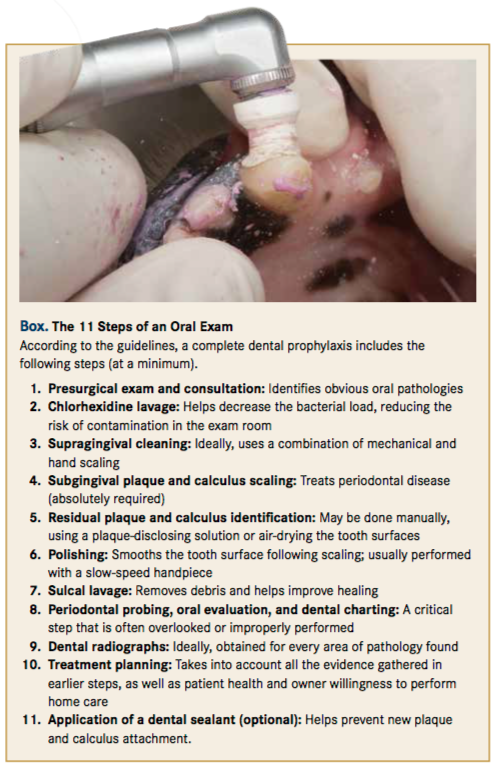

From an animal welfare standpoint, Dr. Stewart explained, a proper dental cleaning includes nearly a dozen steps and involves very sharp surgical instruments to push up and underneath an animal’s gumline, where nerve stimulation occurs (Box). The physical examination should be paired with radiographs to uncover periodontal disease that is undetectable to the human eye. And taking x-rays, she continued, requires placing plates in unusual areas deep inside the mouth. The pain involved in manipulating the mouth, the intensity of restraint required to avoid risks associated with animal movement, and the invasiveness of the procedures themselves must be taken into consideration, according to Dr. Stewart. “Subjecting an animal to a proper complete dental cleaning is absolutely unacceptable without the removal of anxiety, pain, and awareness,” she said.

Dr. Stewart said she hopes that the guidelines’ information on how to perform better oral care—and why it’s so important—will change the way veterinarians view dentistry. After all, dental disease knows no geographical boundaries.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.