Sinoscopy in the standing horse

Sinoscopy is a minimally invasive diagnostic procedure that can be performed on the standing horse. The technique can allow good visualization and treatment of paranasal sinus disease and eliminate the need for more invasive procedures such as large bone flaps. Knowledge of the paranasal sinus anatomy is the most important aspect of the procedure.

Paranasal sinus disorders include primary or secondary sinusitis, progressive ethmoid hematoma, sinus cysts, and less commonly neoplasia. Due to the size and complex anatomy, these disease processes can sometimes be present for weeks or months before clinical signs such as nasal discharge or facial swelling are evident.1 Treatment of chronic equine paranasal sinus disorders can be frustrating, but the long-term prognosis is generally excellent unless the diagnosis is neoplasia.2

Imaging of the paranasal sinuses is critical for diagnosis and surgical planning in affected horses. Radiography and computed tomography (CT) are most commonly used. Sinoscopy is a simple procedure and is minimally invasive compared with traditional surgical approaches to the paranasal sinuses, potentially reducing the incidence of complications. It also provides a way to diagnose more accurately, and subsequently treat, some underlying conditions. Sinoscopy was reported as the most helpful diagnostic tool when compared with radiography and endoscopy in horses with sinus pathology. It provided an exact diagnosis in 70% of patients, compared with endoscopy, at 20%, and radiography at 36%. Changes, including thickened or inflamed sinus mucosa, space-occupying lesions, exudate, dental associated abscesses, and mycotic lesions, can be diagnosed using this modality.1

The horse has 6 paired paranasal sinuses (frontal, rostral maxillary, caudal maxillary, sphenopalatine, and the dorsal and ventral conchal sinuses) that communicate with one another and the nasal passage directly or indirectly. The frontal sinus and the caudal maxillary sinus communicate via the frontomaxillary aperture; the sphenopalatine and the caudal maxillary sinus communicate via the sphenopalatine aperture; and the rostral maxillary and ventral conchal sinus communicate via the conchomaxillary aperture. A thorough understanding of the spatial structural relationships is crucial for successful surgery in the region.3

Sinoscopy can be performed under standing sedation using an arthroscope or sterile flexible fiberoptic or video endoscope via a conchofrontal or rostral maxillary trephine opening. The trephination site is prepared for surgery and desensitized by subcutaneous injection of local anesthetics. Sinoscopy portals are made in the frontal or maxillary bone following skin incisions, by use of a 9.5-mm to 15-mm Galt trephine. Initial irrigation or suction may be necessary to improve visualization if the sinus compartments are filled with exudate. The skin incision is closed with staples or skin sutures after the sinoscopy has been completed.

Sinus compartments that can be viewed directly through a conchofrontal trephine portal include the frontal, caudal maxillary, and dorsal conchal sinuses. The ethmoid turbinates, frontomaxillary aperture, and nasomaxillary aperture are also visible. Structures seen in the caudal maxillary sinus include the infraorbital canal, apices of the maxillary 10th and 11th cheek teeth, the maxillary septum, and the entrance to the sphenopalatine sinus.4 The same structures can be observed via a rostral maxillary trephine opening, but the entrance to the sphenopalatine sinus may not be accessible.

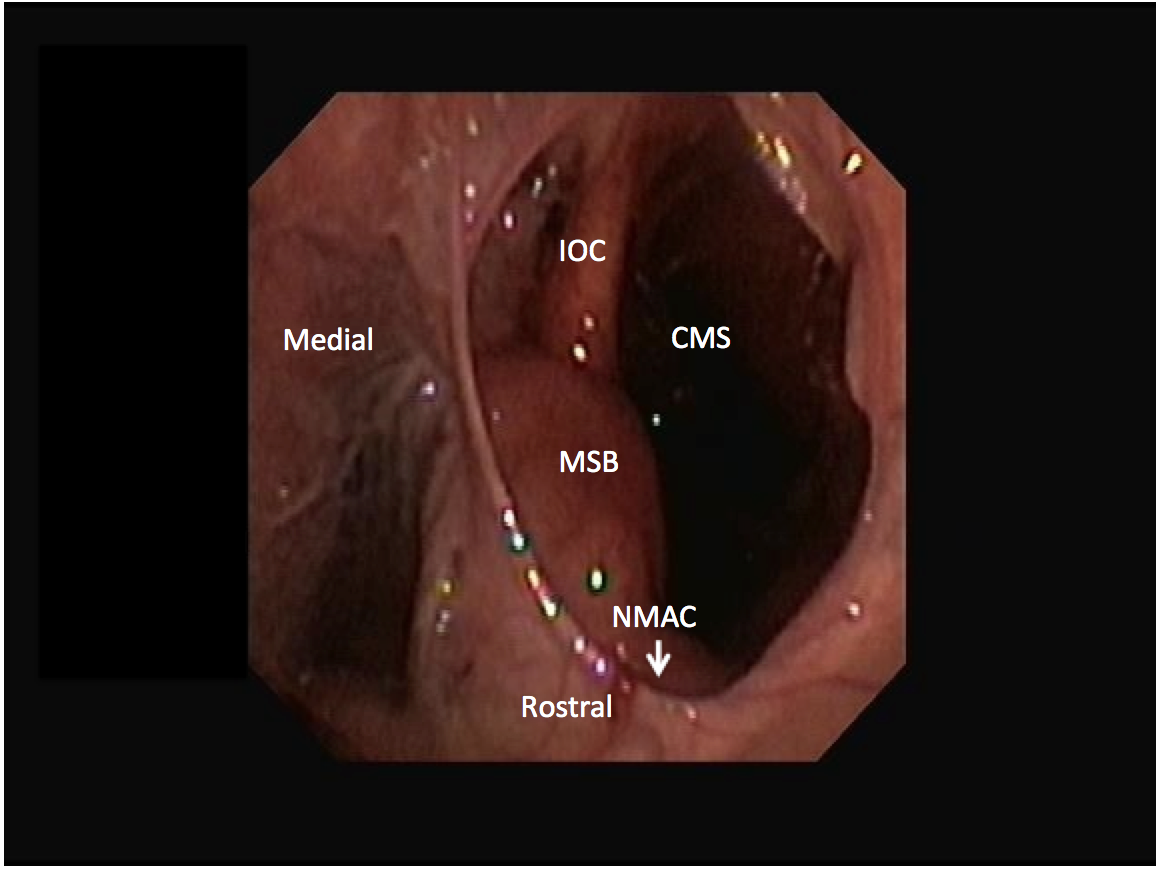

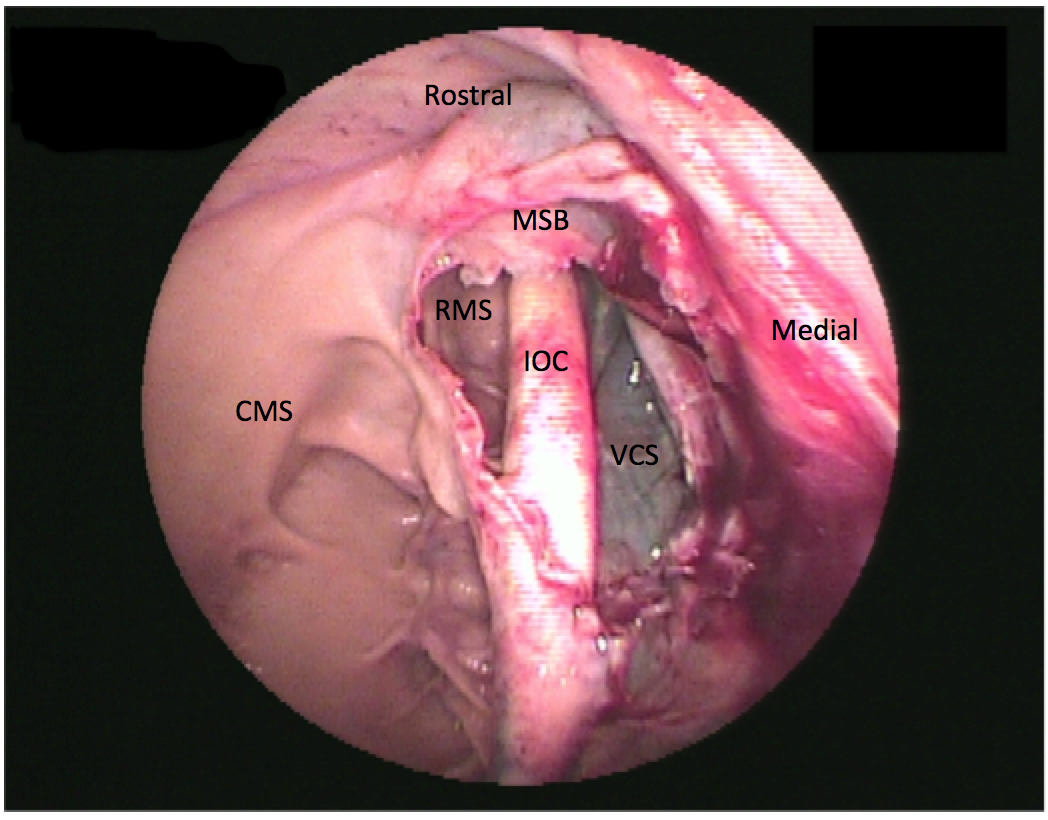

The rostral maxillary sinus and the ventral conchal sinus are frequent sites of infection caused by apical dental infection or inspissated exudate, respectively. However, these sinuses are not directly accessible from trephine holes into the conchofrontal or caudal maxillary sinuses (Figure 1). The rostral maxillary sinus can be examined independently through a rostrally placed maxillary bone trephination. However, this is generally not recommended in young horses to avoid iatrogenic damage to the reserve crowns of the ninth and 10th maxillary teeth. The ventral conchal sinus and rostral maxillary sinus can both be evaluated through a portal into the conchofrontal or caudal maxillary sinuses after fenestration of the cartilaginous maxillary septal bulla (formerly termed ventral conchal bulla). The maxillary septal bulla is desensitized with topical local anesthetics and fenestrated with endoscopic guidance using a Ferris-Smith arthroscopic rongeur, crocodile forceps, or diode laser via the same portal as the endoscope (Figure 2). If fenestration of the bulla causes bleeding that obscures observation, sinoscopy should be repeated after 24 to 48 hours. Lavage of all compartments is possible after fenestrating the bulla.4

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

References

- Tremaine WH, Dixon PM. A long-term study of 277 cases of equine sinonasal disease. Part 1: details of horses, historical, clinical and ancillary diagnostic findings. Equine Vet J. 2001;33(3):274-282. doi:10.2746/042516401776249615

- Dixon PM, Parkin TD, Collins N, et al. Equine paranasal sinus disease: a long-term study of 200 cases (1997-2009): treatments and long-term results of treatments. Equine Vet J. 2012;44(3):272-276. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00427.x

- Tatarniuk DM, Bell C, Carmalt JL. A description of the relationship between the nasomaxillary aperture and the paranasal sinus system of horses. Vet J. 2010;186(2):216-220. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.07.023

- Perkins JD, Windley Z, Dixon PM, Smith M, Barakzai SZ. Sinoscopic treatment of rostral maxillary and ventral conchal sinusitis in 60 horses. Vet Surg. 2009;38(5):613-619. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950X.2009.00556.x

Drs Lindsey Boone and Fred Caldwell are associate professor’s of equine sports medicine and surgery in the department of clinical sciences at Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Dr Zetterström graduated from the University of Copenhagen in 2015 and then worked at a private equine practice for 2.5 years before completing an internship in equine surgery at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute in Lexington, Kentucky. She completed an equine surgery residency at Auburn University in 2021 and is now working at Hallands Djursjukhus, a large private equine practice in Sweden.

Editors note: All veterinary technician content for this month is supported by Banfield Pet Hospital.