Surgery STAT: Pinch and flush: Relieving urethral obstructions in male dogs

By pinching the penis and flushing the urethraand following a few more stepsyou can relieve these painful obstructions and avoid complicated surgical procedures.

Urethral obstructions in male dogs are common in veterinary practice. These obstructions can be difficult to relieve, and many patients are referred to emergency/specialty hospitals still obstructed. It doesn't have to be this way! With a few precise but straightforward steps, general practitioners can relieve most urethral obstructions with minimal fuss to the patient.

Background and diagnostic steps

Canine urethral obstruction is almost always due to urolithiasis. In most cases, the objective of treatment is to relieve the obstruction via retropulsion and extract the urolith via cystotomy. Urethrotomy can result in urine leakage into soft tissues, stricture, persistent hemorrhage, and infection, both perioperatively and long-term, and should therefore be avoided. Scrotal urethrostomy, while more invasive than most patients need, may be appropriate in certain breeds (such as Dalmatians) or in dogs with multiple obstructions. It may also be a better long-term solution in cases of multiple urethral blockages.

Still, almost all urethral obstructions can be relieved and converted to a cystotomy procedure if appropriate treatment is provided. When a dog presents with urethral obstruction, the veterinary team should immediately be aware that this is a painful condition. It's important to consider pain relief medications right away and understand that general anesthesia will be completed to relieve the obstruction. Also, every urethral obstruction should be treated as an emergency because it can lead to urinary bladder rupture.

First, conduct a thorough physical examination, obtain a complete blood count with serum chemistry profile and urinalysis with culture, and take a set of radiographs. When you perform lateral abdominal radiography, be sure to capture the entire rear end of the dog so you can evaluate the entire urethra. In addition, take lateral radiographs with normal limb positioning and also with rear limbs pulled forward to help visualize the perineal urethra.

Also note that these dogs can be azotemic and will need appropriate therapy. In addition, hypercalcemia may be present, which will typically require further diagnostic tests, such as a parathyroid panel.

The pinch-and-flush procedure

General anesthesia with intubation, although it might not seem necessary, is always recommended because it eases passage of the obstruction and relieves discomfort. When the dog is asleep and relaxed and the airway is protected, you should be able to relieve the obstruction more easily. Give a premedication of a narcotic and sedative (e.g. hydromorphone and acepromazine) before inducing anesthesia.

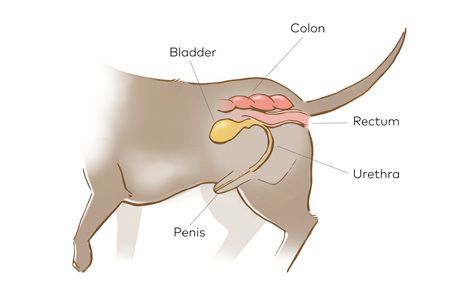

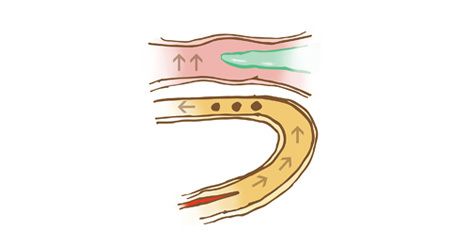

Now the dog is ready for retropulsion of urethral stones. Remember that the premise of this procedure is to flush the stones into the bladder, not to push the stones into the bladder with the catheter. I recommend that three people be involved when available; this makes it easier to maintain sterility and coordinate the procedure. One person is on the catheter, one person is flushing, and one person is rectally occluding the urethra. See Figure 1 for a review of canine anatomy relevant to this procedure.

Figure 1: Anatomical features of the male dog relevant to the pinch-and-flush procedure to relieve urethral obstruction. (All illustrations by Nicholette Haigler.)

Here are the procedure steps:

1. Select an appropriately sized red rubber catheter and a 60- or 30-ml catheter-tip syringe depending on the size of the dog. Prefill the syringes with sterile saline or a 50-50 mix of saline and sterile lubricant mixed vigorously.

2. Place the catheter at the level of the obstruction or just distal to it, adhering strictly to sterile technique.

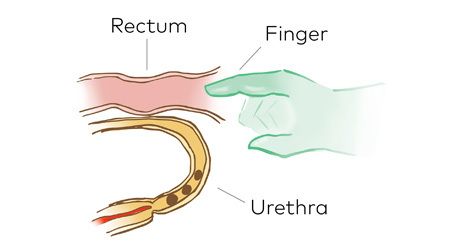

3. Have a gloved assistant place a finger rectally and compress the urethra onto the floor of the pelvis (Figures 2A-2C).

Figure 2A: With a red rubber catheter placed in the urethra, a gloved assistant places a gloved finger in the dog's rectum.

Figure 2B: The assistant presses his or her finger downward (ventrally) to occlude the urethra.

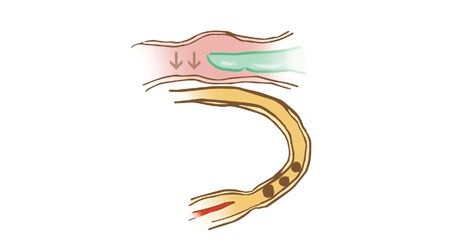

Figure 2C: From the rectum, the assistant compresses the urethra onto the floor of the pelvis. Another team member pinches the distal urethra at the tip of the penis to help distend the urethra while 5 to 10 ml saline is flushed into the catheter.

4. Attach the saline-filled syringe to the red rubber catheter. Lube can be added to the saline for additional viscosity if needed.

5. Pinch the tip of the penis to make sure the urethra is distending while flushing 5 to 10 ml saline into the distal urethra via the catheter.

6. With the urethra distended with saline, double-check that the assistant is detecting pressure rectally while still compressing the urethra. The urethra will be taut and distended distally to the rectal compression.

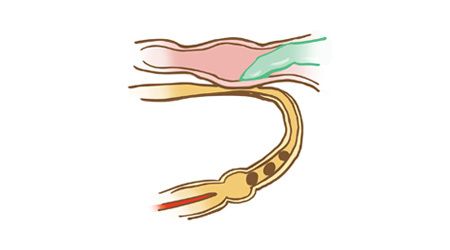

7. As a timed procedure-for example, on the count of three-release the rectal urethral compression and flush the saline with pressure at the exact same moment (Figure 3). Most obstructions will be relieved with one or two attempts.

Figure 3: At the exact same moment, the assistant releases the compression and the doctor flushes saline upward into the urethra. The retropulsion pushes the obstruction back into the bladder, where it can be relieved with cystotomy.

8. Confirm retropulsion of the stones with radiographs.

If the blockage doesn't budge

If this procedure doesn't work and you can't pass a catheter, check the urinary bladder. If the bladder is distended, relieve the pressure by manual expression or cystocentesis. Then create a 50-50 mix of saline and sterile lubricant mixed vigorously to increase the viscosity of the flush. The increased viscosity of this solution helps to increase the resistance and help with retropulsion.

If the obstruction is still not relieved, the next option to try is epidural anesthesia. Typically, placing a preservative-free morphine epidural is enough to help in this situation; bupivacaine can potentially be added for increased muscle relaxation. Repeat retropulsion as needed to relieve the obstruction.

This procedure should relieve almost all obstructions. If the obstruction is not addressed with retropulsion, you may need to perform a urethrotomy or urethrostomy. If the dog needs to be referred, perform a temporary cystocentesis first.

Conclusion

In surgery, avoiding complications is highly desirable. Cystotomy is associated with far fewer complications than urethrotomy or urethrostomy. Retropulsion of urethral calculi causing urethral obstruction accomplishes this goal and is a highly successful procedure when completed correctly. Relieving the obstruction with minimal inflammation and irritation means fewer attempts at catheterization. If you follow these steps to “pinch and flush,” you should successfully relieve the obstruction with only a few attempts.

Dr. Andrew Jackson

Dr. Andrew Jackson was born in Scotland and moved to Minnesota when he was 10 years old. He graduated from the University of Prince Edward Island's Atlantic Veterinary College, then completed an internship in Sacramento and surgical residency in Detroit. Dr. Jackson has been practicing at BluePearl Veterinary Partners in Minnesota for the last nine years. He has extensive experience in emergency, soft tissue and orthopedic surgery. He loves to replace hips, scope knees and elbows, and reconstruct wounds. He loves living in Minnesota-even in the winter.

Surgery STAT is a collaborative column between the American College of Veterinary Surgeons (ACVS) and dvm360 magazine. To locate a diplomate, visit ACVS's online directory, which includes practice setting, species emphasis and research interests, at acvs.org.