Treating diabetes mellitus in cats and dogs: What are your goals?

Nearly all veterinary patients with diabetes are managed with a combination of insulin therapy, diet, and weight management. Here’s the latest.

Nailia Schwarz / stock.adobe.com

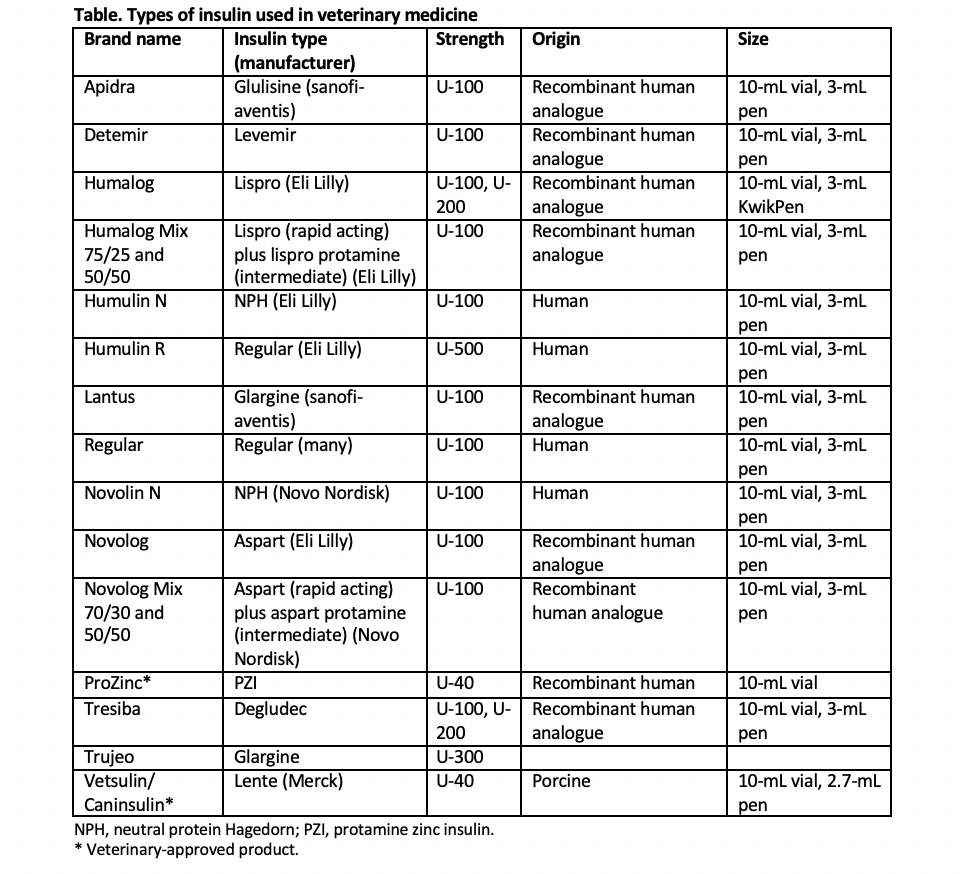

Human and veterinary insulins are categorized by their onset and duration of action, as well as by the protein source from which they are derived. Short-acting insulins are typically used in the veterinary hospital for intensive blood glucose (BG) control, whereas intermediate-and long-acting insulins are used both in hospital and at home for long-term, daily glycemic control. Based on protein source, insulins are human, human analogue (synthetic insulin that is altered from the natural form but retains biological function), bovine, or porcine. Porcine and canine insulins have an identical amino acid sequence, whereas bovine and feline insulins differ by a single amino acid.

Traditionally, veterinarians have managed diabetes in dogs and cats with a variety of veterinary and human insulins (Table). Veterinary insulins include porcine lente and protamine zinc human recombinant insulin (PZI). Human insulins or insulin analogues include neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH), glargine, detemir, and degludec. Pre-mixed combinations of short-acting lispro or aspart insulin with longer-acting protamine insulin are also available as intermediate-acting insulins.

Table 1

Controlling diabetes in dogs

The overall goals for the treatment of canine diabetes include resolving polyuria and polydipsia, maintaining ideal body weight, preventing diabetic ketoacidosis, decreasing the risk for urinary tract infections, and slowing the development of complications (eg, diabetic cataracts) through excellent glycemic control. Ideally, these goals are accomplished while avoiding clinical hypoglycemia. For dogs, the American Animal Hospital Association recommends the use of porcine lente, PZI, or NPH insulin, plus a complete and balanced diet that lacks simple carbohydrates.1

A stable routine for meals, snacks, and exercise is crucial for good glycemic control. Advise pet owners to avoid frequent changes in types and amount of food. Although the ideal diet for diabetic dogs has yet to be determined, recommendations include the following:2-4

- High-fiber, restricted-fat diets, which are high in complex carbohydrates (>45%)

- Diets with moderate fiber and restricted carbohydrates (< 30% metabolizable energy [ME]), which are higher in fat and protein

High-fiber diets may help delay glucose absorption from the gastrointestinal tract and reduce postprandial hyperglycemia. A number of prescription canine diabetic diets with increased fiber are available, although most have carbohydrate levels less than 45% ME. If used with NPH insulin, these high-fiber diets may exacerbate postprandial hyperglycemia in some dogs because peak gastrointestinal glucose absorption occurs after peak insulin action. High-fiber, moderate-fat diets may cause significant weight loss in some diabetic dogs, and thus are not suitable for most lean or underweight dogs.

A variety of commercially available, nonprescription, grain-free diets are lower in carbohydrates and higher in protein and fat, but they have not yet been used in clinical trials with diabetic dogs. Dietary fat restriction (<30% ME) should be considered for diabetic dogs with concurrent chronic pancreatitis or persistent hypertriglyceridemia. It is generally recommended that insulin be given within 1 hour of a meal and, in most cases, for convenience, the meal and the insulin injection are given at the same time.

Controlling diabetes in cats

The primary goal of treatment in feline diabetes is to obtain remission (ie, maintenance of euglycemia without the need for insulin therapy or other hypoglycemic drugs). Remission is possible in about 80% of cats newly diagnosed with diabetes if normal or near-normal BG concentrations are achieved shortly after diagnosis. The probability of remission is increased when a low-carbohydrate (<15% ME), high-protein diet (Hill’s m/d, Purina DM, or others) is used in combination with a long-acting insulin such as glargine or detemir administered twice daily. Lower remission rates are reported using PZI or porcine lente insulin, or when a moderate-carbohydrate diet is fed. Rapid institution of excellent glycemic control, ideally in conjunction with home monitoring, contributes to remission, while institution of tight control (around 6 months or more) following diagnosis is associated with significantly lower remission rates (84% vs 34%).5,6

Because remission often occurs between 4 and 8 weeks of therapy when cats are managed optimally, weight loss is not a major factor in achieving remission. However, weight management is critically important for maintaining remission. Eating does not need to be coordinated with insulin administration in cats, especially if a low-carbohydrate diet and long-acting insulin are used. The type and amount of food and snacks should be consistent each day; snacks must be low in carbohydrates.

Patient monitoring

It’s imperative to consider owner-derived clinical information in conjunction with history and physical exam. Monitor the patient’s water intake, urination, body weight, physical activity, and signs of clinical hypoglycemia. Urine glucose and ketone measurements may also be useful, but BG measurements are the most valuable, particularly when performed at home.

Fructosamine concentration can be useful if there is conflicting evidence for glycemic control (eg, the client reports good clinical control but in-clinic measurements indicate poor glycemic control). Fructosamine can also be useful when clinical information is inadequate or unreliable, or if the owner is unable to measure BG at home. Fructosamine concentrations are more useful for adjusting insulin in relatively stable diabetic cats that have been diabetic for months or years and are unlikely to go into remission. This is because insulin dose is adjusted less frequently in these animals, and knowledge of the average BG concentration over 2 to 3 weeks reflected by fructosamine is more relevant in these cats, but it is not useful for day-to-day insulin dose adjustments in newly diagnosed diabetic cats. Fructosamine concentration gives no information on nadir or pre-insulin BG, only mean BG over weeks.

Monitoring BG at home is invaluable for maximizing the probability of remission. Home BG measurements are typically more accurate because they avoid the spurious effects of patient stress.7-9 At-home monitoring for feline patients also provides more data on which to base insulin dose adjustments, enables accurate assessments for cats that are responding as expected, and is convenient for the owner.

Interest in measurement of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) has seemingly been renewed, possibly given the significance of type 2 diabetes in humans and much commercial advertising of new pharmaceuticals intended to lower the HbA1c of people with diabetes.10 Glycosylated hemoglobin is a hemoglobin product with a glucose molecule attached to its N-terminal amino acid valine. Glycosylation is irreversible and concentration of HbA1c within the circulation is approximately 2 to 3 months (the lifespan of a red blood cell). A dried blood spot test is currently offered (Baycom Diagnostics), yet published data on its performance remain unavailable.

As for cats, single sporadic BG measurements in dogs provide little useful clinical information for monitoring glycemic control. Instead, serial BG concentration curves that follow the same protocol as those obtained in hospital are required. Results must be related to the dog’s clinical signs; interpretation requires an understanding of the complex interactions involved in glucose homeostasis in diabetic dogs.

There is considerable day-to-day variability in BG measurements in diabetic dogs,11 and home-generated serial BG curves are as reliable as hospital-generated curves and have many of the same limitations.

For both dogs and cats, a practical approach incorporates knowledge of clinical signs to guide the timing of home-generated BG curves. If clinical signs are consistent with hypoglycemia occurrence at home, owners must be accustomed to measuring their dog’s BG concentration. This can confirm whether hypoglycemia is present and whether timely treatment is needed.

Samples can be obtained from the marginal vein of the lateral pinna, by collection of capillary blood, or by direct venipuncture. Once the owner becomes familiar with the technique, they usually require considerable practice collecting samples at home before they develop sufficient skill to generate a serial BG curve.

Selecting an appropriate glucose monitor and obtaining reliable glucose readings are essential. Some monitors read whole blood concentration as opposed to serum or plasma values. This causes an “under-reading” effect, in which a true serum concentration of 65 mg/dl will be read out as 50 mg/dl.12 In addition, the distribution of glucose between red cells and plasma is different for cats and humans,12 so human-calibrated plasma monitors may be misleading. Owners should be encouraged to purchase a veterinary-specific BG meter. I recommend the AlphaTRAK (Merck), as this has been well validated.

David Bruyette, DVM, DACVIM, was medical director at VCA West Los Angeles Animal Hospital and is currently chief medical officer at Anivive Lifesciences. He is also CEO of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation and Consultation, and editor of the just-released Clinical Small Animal Internal Medicine.

References

1. Behrend E, Holford A, Lathan P, Rucinsky R, Schulman R. 2018 AAHA diabetes management guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2018;54(1):1-21. doi:10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6822

2. Rucinsky R, Cook A, Haley S, et al. AAHA diabetes management guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2010;46(3):215-224. doi:10.5326/0460215

3. Sparkes AH, Cannon M, Church D, et al. ISFM consensus guidelines on the practical management of diabetes mellitus in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17(3):235-250. doi:10.1177/1098612X15571880

4. Zoran DL, Rand JS. The role of diet in the prevention and management of feline diabetes. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2013;43(2):233-243. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2012.11.004

5. Bloom CA, Rand J. Feline diabetes mellitus: clinical use of long-acting glargine and detemir. J Feline Med Surg. 2014;16(3):205-215. doi:10.1177/1098612X14523187

6. Roomp K, Rand JS. Management of diabetic cats with long-acting insulin. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2013;43(2):251-266. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2012.12.005

7. Casella M, Wess G, Hassig M, et al. Home monitoring of blood glucose concentration by owners of diabetic dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2003;44(7):298-305. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2003.tb00158.x

8. Van de Maele I, Rogier N, Daminet S. Retrospective study of owners' perception on home monitoring of blood glucose in diabetic dogs and cats. Can Vet J. 2005;46(8):718-723.

9. Alt N, Kley S, Haessig M, et al. Day-to-day variability of blood glucose concentration curves generated at home in cats with diabetes mellitus. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;230(7):1011-1017. doi:10.2460/javma.230.7.1011

10. Kim NY, An J, Jeong JK, et al. Evaluation of a human glycated hemoglobin test in canine diabetes mellitus. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2019;31(3):408-414. doi:10.1177/1040638719832071

11. Fleeman LM, Rand JS. Evaluation of day-to-day variability of serial blood glucose concentration curves in diabetic dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222(3):317-321. doi:10.2460/javma.2003.222.317

12. Cohen TA, Nelson RW, Kass PH, et al. Evaluation of six portable blood glucose meters for measuring blood glucose concentration in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235(3):276-280. doi:10.2460/javma.235.3.276

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.