Veterinary culture clash: Are you caring for man's best amigo?

For one in four veterinarians across the country, clients who don't speak English are increasingly common. Here's how two practices tried to bridge the language barrier.

Next >

Imagine a client visit that left everyone so confused you had to call a third party via speakerphone to help salvage the appointment. Or worse, having to stand by and listen while your associate explained crucial diagnostic information to a client, amidst, say, chatting about their weekend. And you had no idea what was being said either way.

Not exactly comforting scenarios. And yet it’s a reality for the nearly 25 percent of respondents to the 2012 Veterinary Economics Business Issues Survey who practice in an area with a significant number of pet owners who speak little or no English.

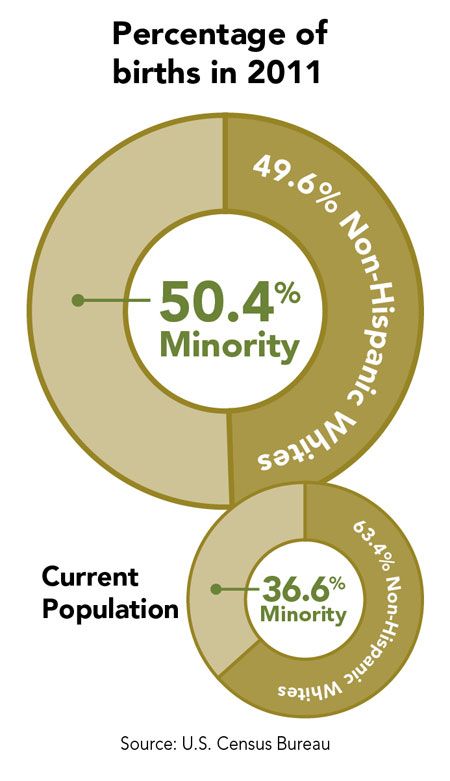

Race, ethnicity, and cultural differences among minority groups have long been sensitive issues for Americans. But they are issues we can’t ignore. New census data released in May marked a milestone—for the first time in history, racial and ethnic minorities make up more than half the children born in the United States. This data marks a tipping point that will undoubtedly change our demographic structure for decades to come.

How this may affect your practice depends on one major element—where you’re doing business. Location is everything for Dr. Jeff Werber, a Veterinary Economics Editorial Advisory Board member with a practice located in Los Angeles, where two-thirds of his staff are English-Spanish bilingual. In his case, there was a readily identifiable business need.

“If you’re practicing in Koreatown without a tech who speaks Korean, you’re losing business—end of story,” he says, “What a client needs is a comfort level that the doctor really understands the problem and knows what to do.”

If you have the client base, hiring bilingual team members to help you develop that understanding between you and your clients is key. (See our chart below for a communication breakdown.) And for Dr. Werber, building that bridge was essential. “If you can’t provide the care you promised, by oath, to the AVMA, just because you can’t communicate, everybody loses—the client, the pet, and your business.”

So what if you’re located in the middle of the map? Nebraska DVM, CVPM Jim Kramer, another Veterinary Economics Editorial Advisory Board member, hired a bilingual receptionist after identifying a large number of Hispanic residents based around a packing plant in a neighboring town. But further research showed that many in the community were relatively indifferent to veterinary medicine and valued pets little more than a neighborhood stray.

“I thought, ‘Let’s extend an arm of friendship to this community and they’ll come in droves,’” he says, until it became obvious that was not going to happen. “I have no regrets in reaching out because I wanted to learn, but protecting my business is different. We made the effort, it didn’t work, and we needed to make sure we were meeting the needs of the people who do come in.”

While these residents were perhaps wary of spending precious resources on pet care, times are changing for the country’s fastest-growing minority group, especially in longstanding communities in California, Florida, and Texas. More culturally assimilated Hispanics are replacing their apprehension toward veterinary medicine with the broader American idea that pets have emotional value to a family and deserve healthcare. By extension, their well-being becomes more of a priority than it once was. By the way, this assimilated group? They speak English, but just might prefer Spanish.

It’s clear it’s a long and winding road to find the sweet spot with minority and non-English-speaking clients. Should you hire bilingual staff members based on your location, so that you can build a solid relationship with clients? Or do your research and come to the conclusion that it’s not worth your time right now? Either way, it’s time to think about it.