Canine Body Language Basics

To evaluate fully the health and well-being of our patients, we need to understand what their bodies are communicating.

When Ariel loses her voice in Disney’s The Little Mermaid, Ursula the Sea Witch reminds her that she still has the power to influence Prince Eric without it. Ursula could easily have been talking to us about one of our patients when she said [insert smarmy tone here], “Don’t underestimate the importance of body language.”

Companion animals “speak” mostly with their bodies, often relaying very little with their vocal cords. When we miss—or worse, misinterpret—our patients’ nonverbal warning signals indicating that they are uncomfortable or worried, we can set ourselves and our staff up for a potential bite. If those of us in the veterinary profession are unable to interpret body language appropriately, how can we expect our clients to be able to understand their pets? We merely need to open our eyes and be good observers of our patients to understand what they are trying to tell us.1

RELATED:

- Scientists Closer to Understanding Animal Facial Expressions

- Do Dogs Communicate More Than We Think?

When we physically examine our patients, we evaluate each body part and diagnostic test result individually and then consider the patient as a whole. The same holds true when we evaluate our patient’s emotional state. We need to look at individual body parts to fully interpret their overall demeanor, keeping in mind that we cannot necessarily interpret a dog’s emotional underpinning without considering its environment and overall emotional history.

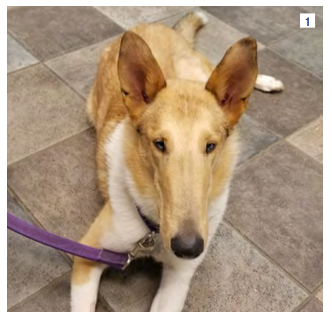

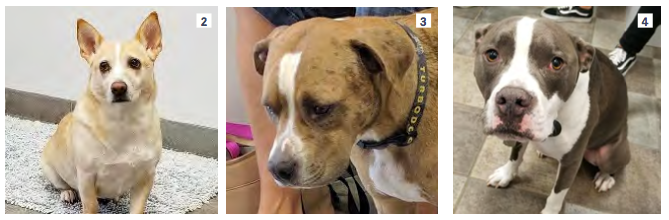

Ears

Ears can be very expressive and their position can change rapidly, so careful monitoring is a must. When the ears are held forward, the dog is alert and attentive to its environment (Figures 1 and 2). Ears held laterally indicate worry or uncertainty such as when a dog is approached by a veterinarian (Figure 3). When the ears are held tight back to the neck—an appeasement gesture—the dog is still worried or uncertain but does not mean any harm toward the person or dog with whom it is interacting (Figure 4).

Appeasement gestures are nonconfrontational body postures meant to indicate to another individual the desire to interact in a friendly way. Commonly the dog will approach with ears back, tail slightly down and wagging, looking at the individual with squinty eyes or increased blinking.

Eyes

The eyes are the windows to the soul, right? At least for our purposes, they can be the window to the limbic system and tell us a lot about how a dog is feeling.

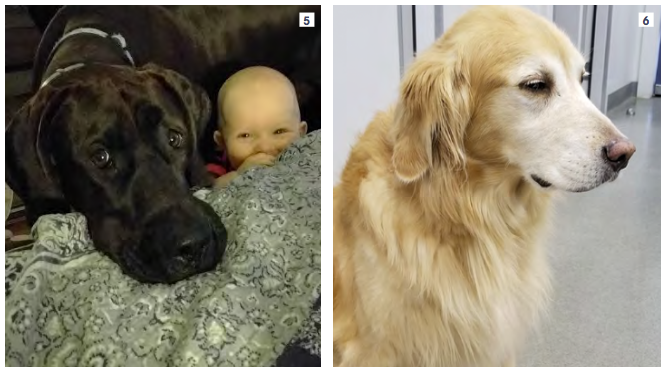

The direction in which the dog is looking can tell us what the dog is thinking and how it feels. Dogs will avoid eye contact as a means to disengage or increase the distance between themselves and others. When they look away but still want to monitor what is causing them discomfort, they will look out of the corner of their eye, causing the whites of the eye to show in the corner, which is called whale eye (Figure 5). Staring directly at something, especially for a prolonged duration, indicates a high level of intensity and interest directed toward what they are staring at and can often be a prelude to aggression.

Other signs of stress associated with the eyes include squinting (Figure 6), rapid blinking, and dilated pupils (despite appropriate cranial nerve function and bright ambient lighting).

Mouth

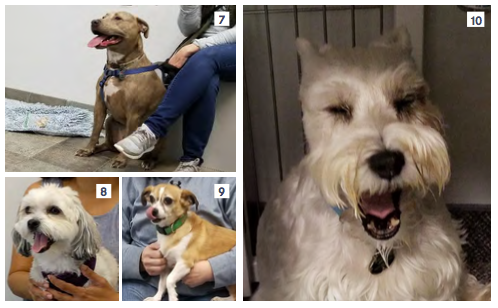

Short of the obvious snarl, many other subtle mouth gestures relay a dog’s emotional state. Tension and tight wrinkles around the commissure of the mouth convey fear and stress (Figure 7). Panting, without recent onset of aerobic activity or a need to dissipate heat, may indicate fear, stress, or conflict (Figures 7 and 8). The dog may also demonstrate several other displacement behaviors, which are coping mechanisms designed to mitigate stress. Displacement behaviors are normal behaviors that occur out of context. Common examples include panting, lip licking (Figure 9), yawning (Figure 10), sneezing, increased exploration, scratching, urogenital checks, and intense chewing.

Tail

A common misconception many people have about canine body postures is that a wagging tail means happiness. In fact, a wagging tail just means the dog is aroused. What is important to note about the wagging tail is its position and height in relation to the body, the tail wag direction, and how fast the tail is moving.

Position

A tail well above the level of the spine indicates high intensity and arousal and can be associated with assertiveness, confidence, or aggression (Figure 11). A tail that is pointing down toward the floor shows appeasement, fear, and stress and is likely the most common tail position we see 12 in our patients (Figure 12). A tail held tightly tucked under the body shows an intense level of anxiety.

Wag Direction and Speed

A dog will bias the direction of its tail wag to the right when presented with a positive stimulus such as the owner.2 The same dog will bias the direction of its tail wag to the left when presented with a negative stimulus, such as seeing a dominant, unfamiliar dog. The speed of the tail wag indicates the level of arousal as well as the dog’s comfort level. A quick, very narrow wag means the dog is highly aroused and is showing discomfort or conflict over the interaction, whereas a slow, sweeping wag indicates comfort.13

Body Position

Weight Distribution

Body weight that is distributed down toward the ground and away from the stimulus is defensive in nature and indicates avoidance, attempts to disengage, or fear. Body weight that is shifted forward and toward the stimulus indicates engagement or assertiveness and can be offensively aggressive in nature.

Rolling Over and Showing the Belly

When a dog rolls over, exposing its belly, this could be an invitation for a belly rub (Figure 13)—or it may not. A dog that shows its belly may be attempting to look very nonthreatening and trying to disengage from the stimulus. The dog in Figure 14 tucks her tail, rolls more to the side to expose her belly, and has tight wrinkles at the commissure of her mouth to indicate her discomfort with the ocular exam. If this body posture is misinterpreted and the human goes to pet a dog that is attempting to disengage, this may trigger the dog to become aroused aggressively.

Evaluating the Whole Patient

It is only after considering individual body parts and posture that we can fully evaluate a patient’s emotional state. However, we also need to be aware that the patient’s comfort level can change quickly depending on what we are doing with them, so ongoing vigilance and monitoring are key.

Signs of canine discomfort during veterinary visits should be pointed out to owners because owners are often unaware of the nonverbal signals their pets display. This knowledge may give them insight into other aspects of the pet’s life that may be causing fear and anxiety, thus preventing future episodes of aggression. Often when a pet bites “out of the blue,” there were early warning signals that were missed by the owners. If we can prevent aggression by educating owners, we preserve the human—animal bond and reduce behavioral relinquishment and euthanasia in the process. Never underestimate the importance of body language.

Dr. Pike graduated from Colorado State University in 2003 and was commissioned as a captain in the US Army Veterinary Corps. She is chief of the Behavior Medicine Division at the Veterinary Referral Center of Northern Virginia and a member of the Fear Free Advisory Committee.

References:

- Aloff B. Canine Body Language: A Photographic Guide — Interpreting the Native Language of the Domestic Dog. Wenatchee, WA: Dogwise Publishing; 2005.

- Quaranta A, Siniscalchi M, Vallortigara G. Asymmetric tail-wagging responses by dogs to different emotive stimuli. Curr Biol. 2007;17(6):R199-R201. doi: 10.1016/j.cub. 2007.02.008.