Hanging with Hafen: 10 features to push for in your hospital

In order to push the envelope in veterinary hospital design, sometimes you have to be a little high maintenance.

Some people are pushy, and that’s okay with me. I like to be pushed. My pushy clients motivate me to do better and do more with less. I remember one particularly pushy veterinarian: Dr. Jon Rappaport. Keep in mind, he’s also talented, inventive, and resourceful—all things I respect in a client.

You may know him from “Ask Dr. Jon” of the PetPlace website. Jon is the founder of the “Web’s #1 Source for Pet Information.” Before he created this website he was the owner of a string of veterinary hospitals. In 1997, we designed a “just right” hospital for him in Aventura, Fla. Our goal: Pack it with as much as we could.

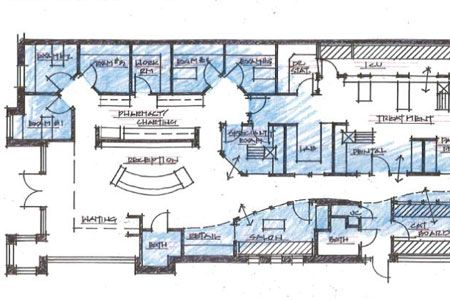

(Click here to view the entire floor plan.)

We stuffed five exam rooms, a specialty procedure room, a three-station treatment area, a one-table dental suite, a 30-cage ICU, a double surgery, retail, a grooming salon, cat boarding, and premium dog boarding all into a 4,900 square-foot leasehold hospital. As if that wasn’t enough, he also wanted to be able to house 100 animals on site. We even added a fun outdoor play area for good measure.

But what makes this a “just right” hospital isn’t just the capacity, it’s the fact that we created an inviting, engaging, exciting, upscale facility while hitting capacity. In order to accomplish our goals, we had to invent some new design ideas (well, they were new at the time). Here are 10 of them you can push for in your new hospital.

1. Install one-door exam rooms

The easiest way to maximize the capacity of any hospital is to use one-door exam rooms. By eliminating the hall behind the exam rooms, you eliminate a chunk of square footage, which is equal to the total width of the exam rooms times eight feet (the width of a hallway with cabinets). In this particular case, that translated to 6 x 8 x 8 or almost 400 square feet. Provided you can screen the doctors coming and going from the exam rooms, and provided you can live with the increased level of traffic that occurs in the one hall, then you can drive square footage out and speed up the circulation and operations within the hospital.

2. Extend the frontage

Another key to maximizing capacity in any hospital is extending the amount of frontage between the exam and medical areas and the waiting area. This is the prime real estate in the hospital. You want as many exam rooms as possible lined up along this frontage. On this plan, the frontage runs along the face of the one-door exam rooms and all the way down the hall. This lease space is only 42 feet wide, so if you had the frontage running perpendicular to the length of the building, you would be limited to four exam rooms. Instead we turned the plan sideways and the public areas extend way, way back—92 feet in fact!

With this hospital, the frontage is a double-sided hallway. I like to think of it as a mall. On either side of the mall you have events for people to see and ways for them to spend their money. The spaces from front to back on the right side of the hallway are waiting, retail, the pet salon, cat boarding, and dog boarding.

On the left side of the mall are the exam rooms, reception, specialty procedure, the lab, the dental suite, and surgery. Not bad for a 4,900-square-foot, rectangular hospital.

3. Scale back the greeter’s desk

A predecessor to the small greeter’s desk that we frequently use now, this was one of our first attempts at driving down the figurative wall between clients and staff. Our ultimate goal is to totally eliminate the typical reception desk and replace it with a staff member holding a tablet like you see at your local Apple store.

4. Let clients sneak a peek

At this point in time, we were really pushing veterinarians to let clients see into the medical areas. The biggest thing people worry about when they take their pet to a hospital is what happens when he disappears into the back. With glass walls, clients can actually see what happens.

5. Make medical theatre magic

Unique to this period of time was also a push toward designing glass-fronted specialty procedure rooms that could also be used as exam rooms. The theory was that the specialty procedure room was a great place to do procedures that clients could watch, effectively creating a medical theatre.

6. Go for the glass

This hospital also had one of the first glass-fronted ICU wards off the treatment area. What’s unique about this one is the size of the ward. Dr. Rappaport had previously practiced in a facility where the treatment area was almost completely surrounded by caging. I have seen this done before on a few hospitals and it’s a very efficient way to house and monitor animals. But it can also drive the doctors and staff crazy with the noise. This oversized, glass-fronted ICU is a great way to keep capacities up while providing visibility.

7. Craft the perfect cat condos

This was one of the first projects where we did glass-fronted cat condos facing into the lobby. This was a novel concept at the time!

8. Don’t completely isolate isolation

In case you haven’t caught on to the theme here… it’s all about client visibility! We placed the isolation ward close to the front in the building. Usually we pull isolation to the back, where it’s only somewhat visible.

9. Reach new heights

We really pushed the capacity of the ward and boarding space, primarily by going vertical. Instead of two tiers of cages in the typical ward, we went to three by putting large cages on the bottom, medium sized cages on the top, and little cages in the middle. The shorter height of the small cage in the middle brings the medium cage down to a level where it can be easily accessed. We also used double-decked runs using glass-fronted doors, which were pretty effective.

10. Run with your outdoor options

This won’t work in Minneapolis, but in Florida we were able to build a covered utility space and outdoor run areas. Dr. Rappaport effectively picked up 1,600 square feet of useable space without directly paying rent on it.

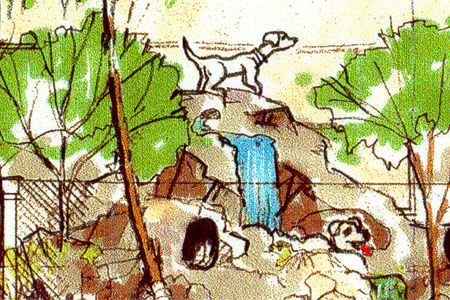

In the first iteration of the plan, we actually investigated developing a fun-filled, engaging, outdoor play yard for dogs. We had a play mountain, a concept where a dog could hang out of the window of a stationary car (equipped with a fan), and a water feature creek for wading. Today you often see play yards and bone-shaped pools, but for the most part these are not areas where dogs can be actively engaged. How about a small wave pool and a sandy beach for the dogs to enjoy?

We’re often bound by convention in what we do, what we think we can do, and for architects and owners, what we think we can design. Veterinary hospitals, much like most everything around us, are a reflection of our social values and the predominant economics.

One of the first companion animal hospitals was built in Raritan, N.J., by Dr. Mark Morris, who invented Hill’s Prescription Diet. At that point in time, most veterinarians were primarily large animal doctors. Suburban, or more precisely “sub-urban,” development was only beginning to take place, primarily as a function of housing springing up around the rail lines that extended out from large urban centers like New York City, or like Philadelphia with its Main Line suburbs of Lower Merion, Radnor, Gladwyne, and Villanova. With the suburbs came families who desired pets, and with that came small animal hospitals. Dr. Mark Morris was a trendsetter. Dr. Jon Rappaport was, too—he pushed the capacity and effectiveness of his “bricks and mortar” hospitals and expanded into the cyber world of veterinary care with his PetPlace website.

As you design and build your “bricks and mortar” facility, what can you do to push your effectiveness? The only limitation is convention. Why not push convention out the window? Don’t forget to be a little pushy.