Why associates won't buy practices-and what you can do about it

Associates are turning away from traditional practice ownership in greater numbers. Can the industry bring veterinary ownership back to life?

Once upon a time, most veterinary school graduates—weaned on a steady diet of entrepreneurial dreams and James Herriott books—dreamed of owning their own practices. After a few years of paying their dues with late nights, weekends, and emergencies, of course, they would follow the predictable path. But somehow that dream has changed. For many associates, it's dead.

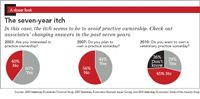

The most recent Veterinary Economics State of the Industry study (August 2010) found that nearly half—45 percent—of associates have no intention of ever buying into a veterinary practice. Only 29 percent still dream of ownership, while 26 percent are unsure. That means 71 percent of associates are unlikely to ever own a veterinary practice. The number has been rising since 2003, when the survey found just 40 percent of associates who didn't want to own. (See the chart above.)

A closer look: The seven-year itch

When I visit veterinary schools across the country, I ask students about their ownership intentions. The results, while not scientific, are very similar. Sixty percent or greater say ownership's not in their plans.

Even though the trend is clear, I personally feel it doesn't have to continue down the same path. It's up to today's practice owners and ambitious associates to set the course for a new form of ownership. This new form was up for discussion at our latest Veterinary Economics Editorial Advisory Board meeting held in conjunction with the CVC in Kansas City. There were lots of big-picture questions up for discussion:

> Who will current practice owners sell their businesses to?

> Will veterinary medicine become a part-time profession?

> What will happen to veterinary compensation when fewer practice owners bear more of the debt risk and earn more of the reward?

> Will corporations increase their ownership of practices?

> Will the entrepreneurial spirit within our profession flicker out?

The biggest question is, of course, why the decline?

Revealing reasons for an ownership decline

I don't want to be overly dramatic, but this decrease in desire for ownership can have a huge impact on our profession. During our meeting, some advisory board members argued that a decreased desire to own stems from the gender shift. A whopping 80 percent of veterinary school graduates are female. And in its study of ownership trends, the latest Veterinary Economics survey found that only 24 percent of women associates want to own a practice someday, compared to 45 percent of men.

Other board members argued that the ownership shift has to do with the diminishing returns of ownership in today's economy or the school debt that today's students now bear upon graduation. Still others said the long hours required for ownership turn off a new generation focused on work-life balance.

Personally, I think much of the problem stems from young veterinarians' lack of positive role models. I hear this all the time when I visit veterinary schools. Many students following in their veterinarian parents' footsteps have watched them work 60 to 80 hours a week while handling night shifts and emergencies. They've seen their parents sacrifice their personal lives. That's their picture of veterinary practice ownership, and they're choosing another path. One student told me, "I don't want to work as hard as my dad. I respect him, but I don't want to be like him."

Recently I received a phone call from a veterinarian who had been in practice for almost 30 years. He had moved back to his hometown after graduation, joined a practice, and, several years later, purchased the business. He fulfilled his lifelong dream. He was married straight out of veterinary school—and not long after that, divorced. He had three children, and he was never able to spend much time with them as they grew up. He handled his hospital's emergencies and worked weekends. He told me he never thought much about an exit strategy; he just assumed he would sell his practice at retirement. He wanted me to help him, but, truthfully, it was too late. He hadn't kept up with changing technology and medicine. The practice had gone downhill and looked old—because it was. It'll be very hard for this owner to sell this practice. He might be lucky if he gets the value for the real estate and tangible assets.

What's more, this man's children resent him because he wasn't there for them while they grew up, and he now resents veterinary medicine and worries about his future and his long-hoped-for retirement.

Is this the role model we want new doctors to follow? Is it any wonder many of our graduates don't want to own a veterinary practice? Yes, there are plenty of practice owners out there who worked long hours and also led fulfilling family lives. But this was not an easy balance to strike. And our children have seen that.

Finding the balance

Practice owners, the times, they are a-changin', and we have to embrace that change. I've spoken to many practice owners who say to me, "I worked 40 and 50 hours a week when I came out of veterinary school and did emergencies every weekend, and I expect a new graduate to do the same. They have to pay their dues." I don't think this mentality is healthy for our profession. The workplace has changed, and we need to change along with it. We need to think about flexible work schedules, part-time ownership, and quality-of-life issues.

I've seen it work. In fact, I have numerous clients who work 40 or fewer hours a week, are still happily married, and are actively involved in family life. I consult with a practice owned by three women, all of whom are married with children. These doctors work about 30 hours a week and follow a four-tier compensation model (see "Making ownership pay" in the June 2010 issue), so they're compensated for their production, their return on investment, their management duties, and their fair division of net profit. All three make a good living, enjoy practice, and say they have a high quality of both personal and professional life. (Learn more from parent veterinarians in "8 keys to having it all".)

Offering solutions

Both successful practice ownership and a healthy personal life are possible—they can coexist quite well. You should ask yourself what adds meaning and value to your life. An employee performance review? Shopping for bargains on inventory? If you're not inspired by those tasks, delegate them. On the other hand, does it add meaning and value to your life to correctly diagnose a patient or perform a successful surgery? Do more of those things.

Veteran veterinarians also need to understand—and model for associates—the fact that a "10" professional life isn't possible without a "10" personal life. Sacrifice one, and you sacrifice the other. Learn to say no and remember you have a right to do that.

And for you owners looking for an associate to buy in, here are a few ways to sweeten the deal:

1. Set an example. Show this generation's associates they can have a life outside the practice and still be a successful owner.

2. Offer flexible work schedules. They appeal to associates and can improve employee retention.

3. Pay fairly. Associates should be paid on ProSal (production with a guaranteed base salary). Owners should be paid using a three- or four-tier compensation program.

4. Leave the door open to part-timers. Consider a potential partner who may work on a permanent part-time basis. Adjust this owner's compensation accordingly.

5. Keep open lines of communication. Mentor your associate, not just in medicine and surgery, but in practice management.

It's past time to show associates that ownership doesn't have to be the end of their personal lives. It can be satisfying and sweet, given the right structure and balance. Open the lines of communication, be willing to adjust, and we just might change the trend. Traditional veterinarian-owned practices don't have to die.

Mark Opperman, CVPM, Veterinary Economics Hospital Management Editor, owns VMC Inc., in Evergreen, Colo. Please send questions or comments to ve@advanstar.com