Is your work a job or a career?

What's the difference between a job and a career, and which would you use to describe the work you do? While some team members deliberately take the veterinary path, others just stumble across it by accident. Regardless of how or why, let's see what the label you've chosen means.

Survey says: a career—at least for 75 percent of Firstline readers, according to the 2007 Firstline Career Path Study. And the numbers prove it. The average Firstline reader has been in the profession for 10.3 years and at the same practice for 6.6 years.

Shawn McVey "I think employees have this idea that doctors want to make all of the decisions. Many doctors make all of the decisions because they think they must. Doctors appreciate team members who take initiative and solve problems."

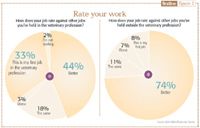

And many of you plan to stick around for a while. About 71 percent of readers say they wouldn't leave their practice for a position in another profession if the new position paid slightly more. But 52 percent said they'd leave if the new profession paid a lot more, 41 percent said they'd leave for better benefits, and 39 percent said they'd leave if the new profession had more potential for advancement. Bottom line: You like your career, but there's still room for improvement (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Job vs. career

So what's the difference between a job and a career? "People who are in jobs wait for their work to define them," says Shawn McVey, a Firstline Editorial Advisory Board member and the CEO of Innovative Veterinary Management Solutions in Phoenix. "People who are in careers define their work."

It's a mindset, says Sheila Grosdidier, BS, RVT, a Firstline board member and a consultant with VMC Inc. in Evergreen, Colo. "People in jobs wait for someone to tell them what to do. People in careers look at trends and make recommendations," she says. "They see themselves as partners with their clinics, and they know their recommendations help grow the business and develop their careers."

Career-minded people also share a few other characteristics, Grosdidier says. They look for ways to enhance their skills to meet the practice's needs. And they're committed to an ethical standard. "People in jobs can be ethical, too," Grosdidier says. "But people in careers are working to influence the direction of the profession."

Mark the trend

McVey says he predicts a trend toward more careers in veterinary medicine as more practices continue to expand and make more money. "As practices grow, they will need more systems and more internal mid-level management support," he says.

Grosdidier agrees. She sees more opportunities for team members, and this gives team members more control over their career paths. "For example, we're in a market where there are many opportunities for technicians," she says. "So if you're a technician working in a practice where you don't feel appreciated and utilized and you don't have any opportunities to grow, you have other options. There are practices that would love to hire you. So you can settle, or you can choose to be part of an evolving practice."

Want a career attitude?

It's simple. Look for problems and fix them, McVey says. "Find a problem and present it to the owner in analytical terms," he says. "What is the cause, what is the effect? What is your plan to fix the problem, and what will it cost?"

Can't pin down the doctor? McVey recommends writing the problem and solution on paper and submitting it with a request for a meeting. "It's a joint effort," McVey says. "Employees must take ownership of their work situations and bring solutions to doctors. And doctors must be willing to relinquish control. Sometimes, doctors don't know they need to let go until someone shows them."

The key to success: Make your suggestion time-specific. If you want to change the way you handle client callbacks, change it for two weeks. "Tell the doctor, 'If this doesn't improve the bottom line or make your life easier, we can go back to the way things were before,'" McVey says. "Most doctors are very receptive to this."